Cultivated Variety

Monday, 17 February 2014

At Konstanet by Marten Esko and Epp Õlekõrs

“With the recent furor over art writing, namely the coinage of the term ‘International Art English’ and the ongoing crisis in art criticism, a focus has been put on how to evaluate, judge or examine art through and with the means of text. But another piece of textual output, which often accompanies the notorious press-release, and which, in some circles, carries out a stronger judgment than any form of criticism has somehow, in most cases, been left aside. This previous sentence is, of course, referring to the artist’s curriculum vitae – the sum of everything an artist has accomplished, an international art world passport, or more accurately a breed certificate, according to what, art world or art market professionals make the judgment of value.

But this form of text is not in any way connected with art criticism as a discipline, yet, in a peculiar way, does it actually originate from what could be called the ‘field of art’. Supposedly, the first person to create a professional CV was Leonardo Da Vinci in 1482, when he outlined his experience in rock flinging and creating lightweight bridges. In comparison to criticism evolving as a textual means of expression of the ideas concerning art in the broadest sense, the CV has its history in the field of employment, as could also be seen with Da Vinci. Simply put, it is a bureaucratic means for evaluating one’s accomplishments and qualifications in a compressed textual format, which leads to a possibility to attain seemingly objective, yet still judgment-based results.

Here the main question is, ‘to whom are these seemingly objective results meant?’, or more directly, ‘for whom does the artist’s CV exist?’. It seems unnecessary for the ‘common’ audiences contemplating the works in the exhibition context, for it adds nothing, in the artistic perspective, to the presented work. Yet it is always present, mainly because it provides information about the primary (external) context of an artwork – the artist. But still, this information is not meant for the average visitor; it is not a short biography but a CV. Therefore, the answer to this previously stated question about its aim is, with some generalization – the market.

Would this mean that the art market is the employer for the artists, who tirelessly try to push their CVs through the gates of the art world and the art market? Looking at the market–artist relationship through the employer–employee relations of power, casts doubt on the independence of an artist and raises the question about future growth of the amplitude of market influence. The change is taking place already, as a certain segment of professional art has its primary output aimed towards fairs or the auction houses, thus, making the exhibitions seem as side-effects or formalities that have to be dealt with in order to gain future validation.

This skeptical position, however, correlates with the institutional theory of art, which, simply put, suggests that the ‘final decision’, if something is a work of art or not, is made by the art world’s institutions, however when we look at the way CVs function, institutions, in a wider sense (e.g. museums, galleries, biennials, professional journals, art magazines, fairs) are also the ones who comprise ‘objective’ criteria for the judgment. By being associated with certain institutions – via an exhibition, a nomination or an article written about – develops this background, by which, firstly the artist and then his or her work is evaluated. The problem lies in this previously stated sequence, which has initiated a shift from evaluating an artist by what he or she produces to assessing the production according to its author.

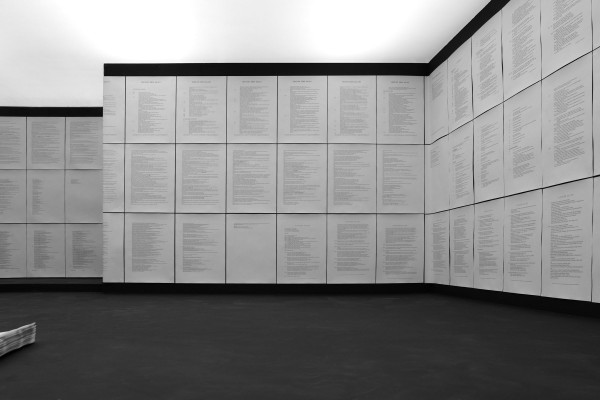

Finally we come to the question of the title of this exhibition. There is more to it than matching initials, for ‘cultivated variety’ refers, in the sense that something, for example land, is altered to suit the needs of the owners, to an artist who has been cultivated to suit the needs of the art world and of the art market. The 23 artists, whose CVs are included in this exhibition, are the only ones listed in the ArtReview’s 2013 Power 100 index. These artists comprise the crème de la crème of today’s contemporary art world, but the fact that, from the ‘ranked list of the contemporary art world’s most powerful figures’ less than a quarter are actually artists, speaks for itself.

This exhibition is not an ironic commentary on the already established personae, as it is not suggested that these artists themselves are the cultivated varieties, on the contrary, they are the parent plants from which many can be produced. One could imagine the gallery space as a repository of rare and valuable sources (e.g. plants or artists) which satisfy the current market demand while, at the same time, making an influence on the future generations and leaving their marks on history. For this exhibition, CVs also take on the role of artworks, as they are meticulously crafted compositions – masterpieces in the art world’s commercial landscape.

Therefore the exhibition works rather as a skeptical hypothesis on the growing influence of the art market and on its relation to the future of the art world. The dominance and predominance of the market and its further influence on the actual production of art, is that what is in question here. How far reaching will the influence be and what precisely will follow, is yet to be witnessed, but these developments should not in any case be overlooked, for they might turn out to be the actual course alterers.”