Ilanit Illouz

Thursday, 11 December 2025

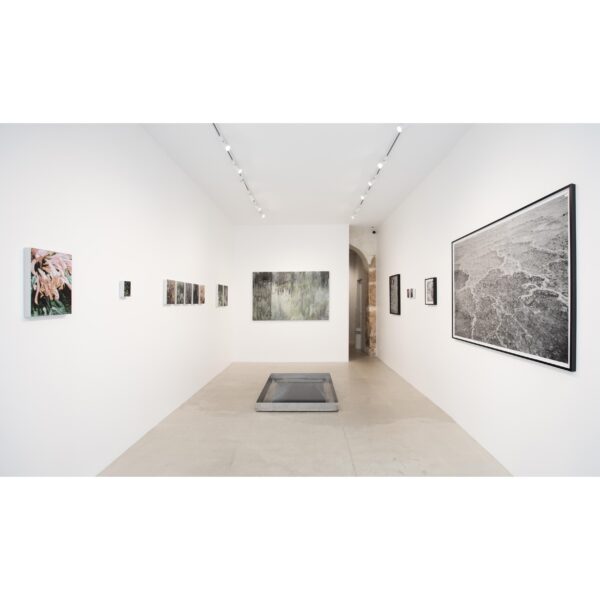

Work from The Memory of Landscape.

“For me, Ilanit Illouz is not an artist but an archaeologist. Like an intrepid excavator, she travels through the landscape, walking the desert in search of what is hidden, undiscovered. In a certain way, her research-driven approach is no different from that of an archaeologist—demonstrating an equal commitment to studying the human past through its material traces, whether that past is ancient or recent. Even her works are “fossilized,” infused with the raw fabric of time—dust, sand, salt, earth, and minerals. Like an archaeologist, Ilanit Illouz goes in search of ancient places: the Mediterranean, the Dead Sea, and the Judean Desert. Lands that remember and commemorate, and others that are now erased.

She asks herself: How can one evoke a place whose landscape has left no trace?

Ilanit Illouz’s work serves to create a memory and a place where none exists. A translation of the untranslatable.

She meditates on personal and collective traumas, paying homage to her mother and to countless others who traveled great distances in search of a better life. In the case of Illouz’s mother, migration took her to Algeria, Marseille, and Kiryat Ata (in northern Israel). Her abstract landscapes thus represent the sociopolitics of territory, borders, geography, and independence. They are decidedly anonymous—a choice I see as intentional and metaphorical—representing simultaneously somewhere and nowhere, or the thin line between personal and universal experience.

Ilanit Illouz’s works are “political landscapes” for the histories and memories they contain, but also for the narratives they seek to foreground. The artist’s unique process is essential here, taking the form of a kind of “intervention”—an act of excavation and delicate gathering of organic materials. I picture Ilanit Illouz bending down to retrieve salt, earth, and sand, and in return leaving a part of herself embedded in the ground. The artist creates a physical mark on the landscape—or perhaps it is more of an exchange? A collaboration, or even a performance? I imagine the land sacrificing itself for Ilanit Illouz in order to be remembered. The idea of “taking” echoes in my mind. Taking photographs, or taking something that does not belong to us—land, a home, or someone’s rights.

Many of Illouz’s destinations are the sites of both contemporary and historical conflicts, often centered on the land itself—which, through the artist’s hand, crystallizes and takes form on the surface of her prints. These are also places implicated in modern battles over natural resources, notably the Dead Sea, whose precious salt is at the center of an international boycott due to illegal exploitation. The Dead Sea is also facing a climate crisis and is shrinking at an alarming rate—about one meter per year. In the last fifteen years, 1,000 sinkholes have appeared—depressions that open in limestone regions. The French word for “sinkhole,” the artist’s mother tongue, is “doline,” the title of her ongoing series.

Extraction and our seemingly insatiable appetite for natural resources mark our landscapes in their own way. More recently, Illouz’s work has taken her to volcanic regions of Italy. Here, the earth remembers the seismic activity of its past and its impact on the scarred landscape and the civilizations that once inhabited it. Volcanoes are both witnesses and traces of the past. The artist describes her interest in history as “autobiographical, geological, mineral, and vegetal.” Thinking of volcanic matter—lava, dust, and stone—brings to mind the myth of Medusa, wronged by men, exiled, and endowed with the terrible power to turn men into stone. To “petrify” them, in a way reminiscent of the fossilization protocol used by Illouz. Medusa represented an otherness that could not be understood and therefore had to be destroyed. After Perseus cut off her head, Pegasus and Chrysaor emerged from her body. A transformation—a new life born from death. Volcanic regions are hostile, and yet life finds a way to survive, sometimes to flourish.

By using organic materials and excavation-like techniques, Ilanit Illouz highlights environmental pressures on geology, landscape, limnology, ecosystems, and Earth’s climate, as well as the effects of the Anthropocene on ancient worlds. By taking very little, she reveals many phenomena; her physical interventions symbolizing both mining and, more broadly, the manipulation of soil, as well as the building of dams. For the artist, the use of salt is particularly meaningful. Its complex history as a commodity of exchange intersects with its role in the historical and technological development of photography. Photography is, at its core, a process born of the industrial and imperial era.

Salt, too, has crossed continents and oceans, shaping political, social, and economic dynamics along the way. It preserves but also degrades—a metaphor for the fragility of our environment and the dynamics of political power. Pioneers Thomas Wedgwood (British, 1771–1805) and Joseph Nicéphore Niépce (French, 1765–1833) developed early salt-printing processes but could not find a way to fix or stabilize their images. William Henry Fox Talbot (British, 1800–1877) made improvements around 1834 using a saline solution. The use of natural resources to capture images was further developed by Niépce around 1822 with the creation of the heliograph. This process involved bitumen of Judea, a light-sensitive material applied to a pewter plate. It produced the earliest known photograph made directly from nature, View from the Window at Le Gras (1826 or 1827).

There is a true alchemy in Illouz’s work, a formal beauty in the physical materiality and artisanal gestures of her practice. It is painstaking work, marked by great meticulousness. After collecting her organic materials, she returns to her studio. Like Wedgwood, Niépce, and Talbot, she creates and applies a solution to the surface of her photographic prints—often repeatedly and over several months. A transformation takes place. The result is otherworldly: a lunar landscape shimmering with millions of diamonds. A Trojan horse concealing its complexity and drawing the viewer in.

Ilanit Illouz emphasizes the cathartic dimension of the whole process—walking, gathering, remembering, washing, erasing, forgetting. To me, her prints are an act of resistance. An alternative archive of history. A new form of life emerging from the roots of the past.” – Fiona Rogers (translation)