Hans Richter

Wednesday, 18 September 2013

Rythmus 21 & 23.

“Richter, on the other hand, decided to adopt an entirely new strategy: rather than attempting to visually orchestrate formal patterns, he focused instead on the temporality of the cinematic viewing experience by emphasizing movement and the shifting relationship of form elements in time. His major creative breakthrough, in other words, was the discovery of cinematic rhythm, which he then used as the title of his first film, Film ist Rhythmus: Rhythmus ’21 (Film is Rhythm: Rhythm 21, 1921). For Richter, rhythm, “as the essence of emotional expression”, was connected to a Bergsonian life force: ‘Rhythm expresses something different from thought. The meaning of both is incommensurable. Rhythm cannot be explained completely by thought nor can thought be put in terms of rhythm, or converted or reproduced. They both find their connection and identity in common and universal human life, the life principle, from which they spring and upon which they can build further’.

The determining impulse for all of Richter’s early film work, visual rhythm, as articulated time, was used to organize the constituent spatial elements of a film into a unified whole.

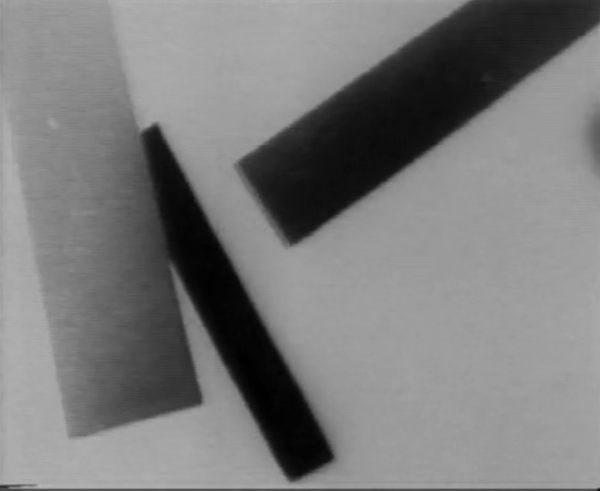

In Rhythmus ’21, generally considered to be the first completely abstract film, Richter used these principles to create a work of remarkable structural cohesion. Completed by using stop motion and forward and backward printing in addition to an animation table, the film consists of a continuous flow of rectangular and square shapes that “move” forward, backward, vertically, and horizontally across the screen. Syncopated by an uneven rhythm, forms grow, break apart and are fused together in a variety of configurations for just over three minutes (at silent speed). The constantly shifting forms render the spatial situation of the film ambivalent, an idea that is reinforced when Richter reverses the figure-background relationship by switching, on two occasions, from positive to negative film.

In so doing, Richter draws attention to the flat rectangular surface of the screen, destroying the perspectival spatial illusion assumed to be integral to film’s photographic base, and emphasizing instead the kinetic play of contrasts of position, proportion and light distribution. By restricting himself to the use of square shapes and thus simplifying his compositions, Richter was able to concentrate on the arrangement of the essential elements of cinema: movement, time and light. Disavowing the beauty of “form” for its own sake, Rhythmus ’21 instead expresses emotional content through the mutual interaction of forms moving in contrast and relation to one another. Nowhere is this more evident than in the final “crescendo” of the film, in which all of the disparate shapes of the film briefly coalesce into a Mondrian-like spatial grid before decomposing into a field of pure light.

According to Richter, the original version of Rhythmus ’21 was never shown publicly in Berlin. At the behest of Theo van Doesberg, however, it was shown in Paris in 1921, with Richter introduced as a Dane due to anti-German sentiment. In May 1922, Richter travelled with van Doesberg and El Lissitzky to the First International Congress of Progressive Artists, where they formed the International Faction of Constructivism. In a group manifesto, written by Richter, they define the progressive artist ‘as one who denies and fights the predominance of subjectivity in art and does not create his work on the basis of random chance, but rather on the new principles of artistic creation by systematically organizing the media to a generally understandable expression’.” – Richard Suchenski