Matt Lipps

Monday, 9 June 2014

Work from his oeuvre

“Matt Lipps recently confessed to me that, during his adolescence, he owned a lifesized poster cutout of the 1990s siren and Melrose Place habitué, Alyssa Milano, which was tacked above the frame of his bed. It was an early intimation of the themes Lipps now examines in his work: the transference of desire onto images of printed media and the need to physically locate them within intimate spaces. It’s an act of totemic association, investing a massdistributed image with the deeply personal. Lipps’s work today involves cutout images – often sourced from discontinued photographic publications – that are first arranged into carefully constructed and lit still lifes, then photographed with a largeformat, analogue camera.

In earlier work – notably from his time as a graduate student under Catherine Lord’s guidance at the University of California, Irvine – Lipps drew heavily upon themes of sexuality, appropriating pictures from gay magazines for use in his pieces. During this period, in which the artist came to grips with his queer identity, his use of pornographic materials followed a sexual bildungsroman common to many – a secretive education gleaned from the pages of lessthanseemly reading material. As with Untitled (blue) (2004) – part of his ‘70s’ series – Lipps constructed miseenscènes that literally transplanted the object of lust into the domestic sphere. Propped up by small dowels and toothpicksized sticks, the cutout eroticized figure is placed atop crests of heaving bed sheets, set against a blue, seemingly nocturnal backdrop, mordantly blurring the lines between the desired and the disembodied.

With his inclusion in the 2009 group show ‘Living History II’ at Marc Selwyn Gallery in Los Angeles, and his 2010 solo exhibition ‘HOME’, at San Francisco’s Jessica Silverman Gallery, Lipps traded the erotic for the domestic. Included in his ‘home’ series, the large photograph Untitled (bar) (2008) is set in his familial living room. Fractured into abutting coloured panes, the suburban location is foregrounded by a jagged, crevicescarred black and white form supported by a sliver of wood. True to his photographic roots, Lipps later told me this shape was taken from an Ansel Adams monograph. In all the images from the series, the disjointed planes of familiar interior scenes juxtaposed with displaced natural forms evoke something akin to the lurking sense of Sigmund Freud’s unheimlich, or ‘uncanny’. For Lipps, the great unknown would seem to begin at home. And it is, perhaps, a personal sense of dislocation that looks to have coloured the artist’s more recent fascination with structures of taxonomy. Lipps’s 2010 show ‘HORIZON/S’ took as its starting point the nowdefunct bimonthly arts publication Horizon, which ran from 1959 to ’89. Among the photographs presented in the series ‘Untitled (Women’s Heads)’ (2010), Lipps arranges a cast of female cutouts, all at various angles of pose – seemingly random women grouped together by their shared gender. Meanwhile, in the panel of six photographs that comprise Untitled (Archive) (2010), a grand assemblage of cutouts, used in the production of the other still lifes, falls somewhere between the sitespecific sculptures of Geoffrey Farmer and Aby Warburg’s search for art historical forms in his Mnemosyne Atlas (1927–29).

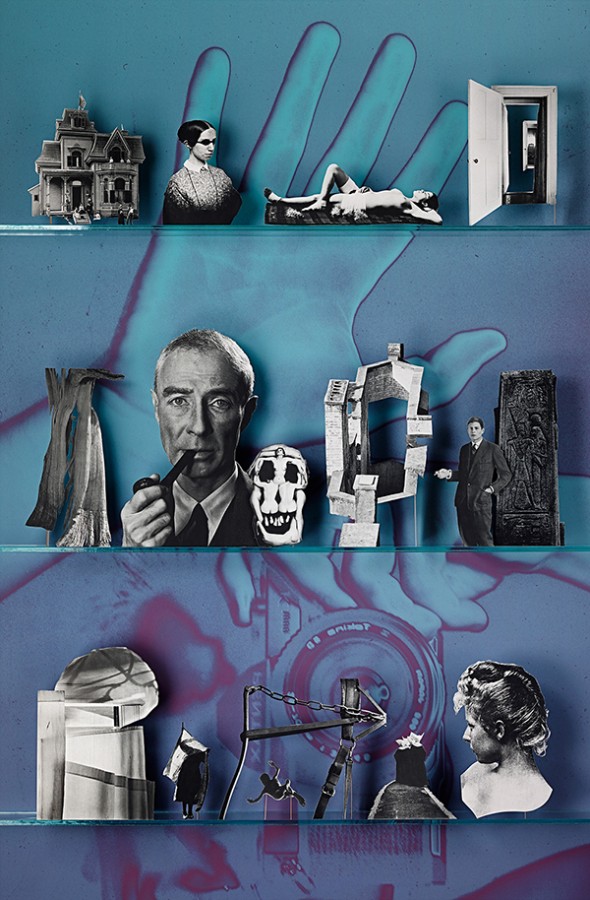

Lipps’s current body of work, ‘Library’ (2013–14), continues this interest in the disruption of the archival. Similar to ‘horizon/s’, the current series began with the discovery on an outofprint pub lication, in this case a 17 volume TimeLife series titled The Library of Photography (1970–85). With issues dedicated to topics including ‘Photojournalism’ and ‘Children’, the series intended to present a concise historical and technical overview of the medium. Lipps’s interest, as he explained it to me, lies in the systematicity the series applied to the photographic act and, by extension, to the photograph itself. In Nature (Library) (2013), neatly linedup black and white cutouts of wildlife and geological formations are intermixed with images of analogue cameras being adjusted by disembodied hands. Standing on glass shelves, they are set against a background colour photograph of a cactus, saturated in electric hues of purple and cyan. In many ways, Lipps’s ‘Library’ series photographs recall the portable protomuseums of the late renaissance. Those historic wunderkammers were intended to be symbolic of their owners’ control over the natural world, heralding a nascent enlightenmentera fervour to classify just about everything. However, while for the renaissance collector the cabinets symbolized humanity’s empirical rule over nature, Lipps’s ‘Library’ highlights the subjectivity underlying such claims to universal association. In the age of the collective hashtag, in which disparate images are grouped together by a communally archivehappy zeitgeist, Lipps draws upon narratives which are undoubtedly his own.” – Frieze