Aleksandra Domanović

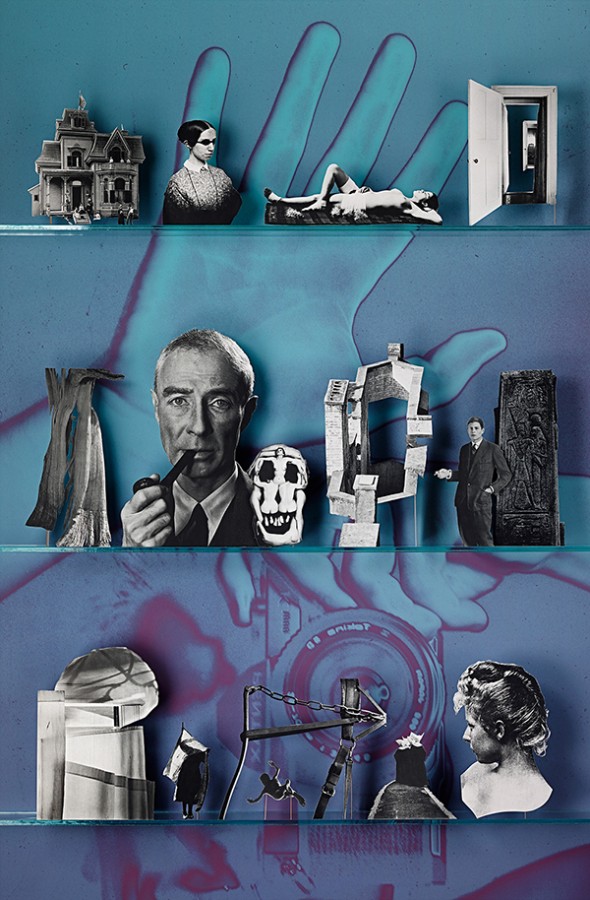

Work from From yu to me

“Aleksandra Domanović used to own an international sampler of domain names: aleksandradomanovic.sk, aleksandradomanovic.rs, aleksandradomanovic.si, aleksandradomanovic.eu. It’s usually enough for an artist or other public figure to claim their name on .com, and Domanović did, but by staking out real estate in the top-level domains governed by Slovakia, Serbia, Slovenia, and the European Union she reminded herself, and anyone else paying attention, about the friction of states and networks, names, and domains. Domanović was born in Yugoslavia, and when it was gone her citizenship drifted. If for some of its users the World Wide Web appears boundlessly ephemeral in comparison to the permanence of statehood, in Domanović’s experience of recent history, states and domains alike are tools of control that can be surprisingly fragile and flexible.

The domains in Domanović’s personal collection, which have since expired, sketched an outline of those ideas. Her new video adds details. From yu to me is about the history of the internet in Yugoslavia, or what used to be Yugoslavia.

It’s hard to talk about the internet and Yugoslavia together. The domain name assigned to it—.yu—is a curiosity, because the country that gave it its name coexisted with it only briefly, and in that time only a small population of specialists used it. What’s more, during the Balkan war of the early 1990s, the Serbian government that claimed Yugoslavia’s mantle was disconnected from the internet by UN sanctions, and .yu was administered by independent Slovenia. From yu to me—the title describes a distance, but not a linear one measured by the spatial or temporal coordinates of maps and timelines; rather, it covers a system of overlapping forking paths.

Here are some facts about .yu and .me: In 1989, .yu was registered by a Slovenian agency just as the country seceded from Yugoslavia. After several years’ delay, it was reassigned to the so-called “third Yugoslavia” (Serbia and Montenegro) in 1994. Montenegro was issued .me to go with its new UN membership after the nation voted for independence from Serbia in 2006. Through all of this, the .yu domain stayed under Serbian control until ICANN, the non-profit that coordinates the internet’s global domain system, finally abolished the domain it in 2010. (Meanwhile, .su—the top-level domain for the Soviet Union, which was registered 1990, fourteen months before the Soviet Union collapsed—continues to exist, as domain holders lobby ICANN to keep it alive.)

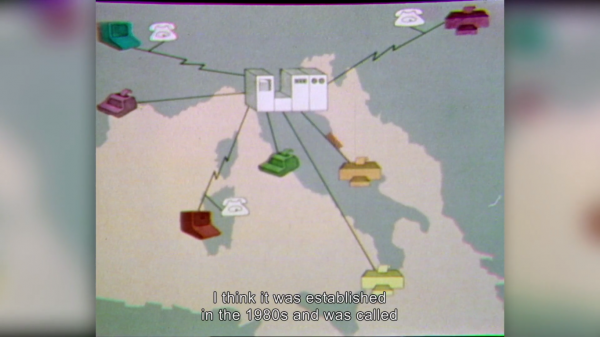

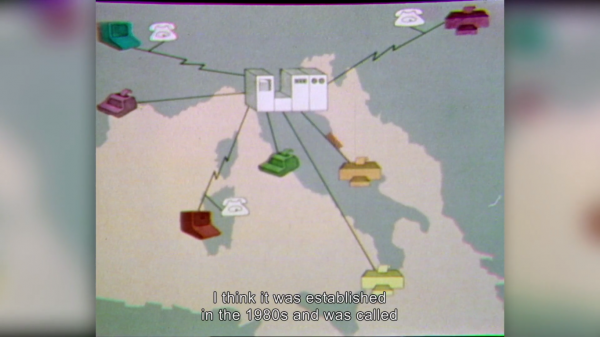

There’s not really much about .me in From yu to me, though it’s noted in passing that Montenegro is making quite a bit of money from it. Domanović’s main interest is .yu. She tells its story through interviews with two women—Borka Jerman-Blažič, who registered it, and Mirjana Tasić, who oversaw its transfer to Serbia and administered it until 2007—and ends on a conversation with a curator who acquired the domain for the collection of the Museum of Yugoslav History in Belgrade, following the model of the Museum of Modern Art’s acquisition of @. Jerman-Blažič and Tasić share anecdotes of connection and disconnection—how they implemented a closed, national network before Yugoslavia was connected to EARN (the European counterpart to ARPAnet in the United States), the collapse of email when Slovenia was bombed in 1991, the ensuing struggle over the ownership of .yu between Slovenia and the authorities in Belgrade, and email exchanges explaining the need for new domains to match new UN memberships with internet administrators in California and elsewhere who knew and understood nearly nothing about Balkan politics.

Maps barely appear in From yu to me, and though Domanović sets up her interviews with establishing shots that show her in unheard conversation with her subjects in courtyards and corridors, she doesn’t give datelines, so there’s no way of telling whether footage was filmed in Ljubljana or Belgrade or somewhere else. Geography flickers indistinctly but networks feel solid: they come in alive in the reminiscing of Tasić and Jerman-Blažič, who worked with the massive mainframes seen in the archival footage Domanović uses, and dealt with the daily bureaucracy that accrued around them.

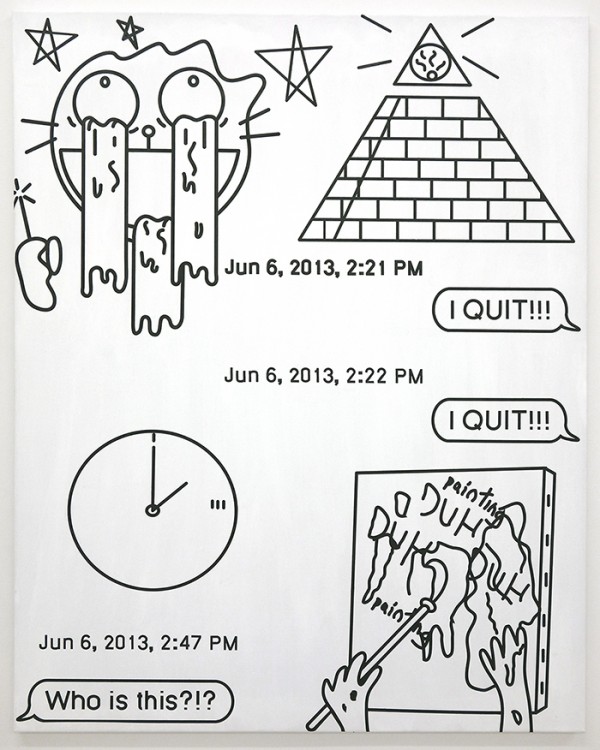

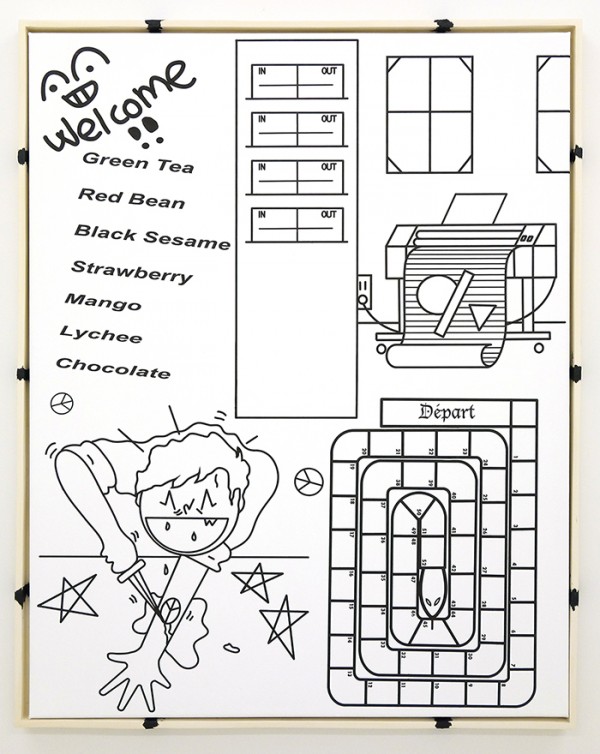

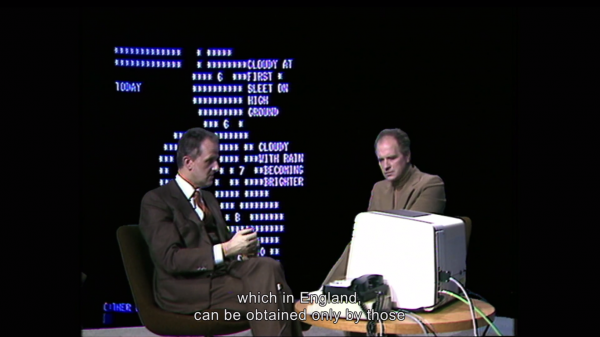

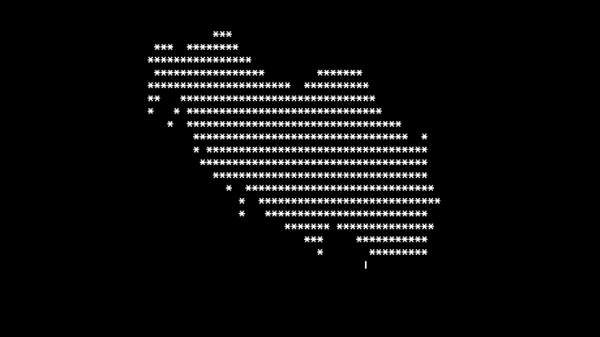

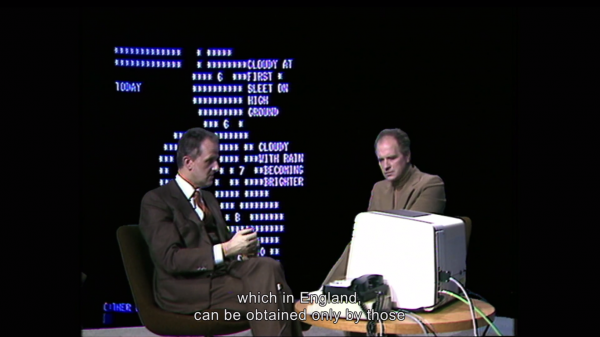

The stories of From yu to me are from a time when email was like the telegraph, a fast way of sending information that people used rarely because it required a visit to specialized facilities. The stories predate many of the utopian and dystopian network fantasies of the nineties—the Declaration of Cyberspace Independence, The Matrix—that imagine the web as an autonomous social space. Instead, the internet is discussed in highly pragmatic terms. There are scattered expressions of wonder at the possibilities of high-speed communications networks, but they look quaint and silly. A drowsy anchor in a beige turtleneck says: “Computers or better TV networks will soon enable us to connect with various databases from different computers,” and reads a weather report for England from an ASCII map of the United Kingdom that appears on a little blue screen.

Other than the news clips, all the archival footage in the video is fuzzy on either side and sharp in a square in the center, like a microscope slide, as if to represent the clarifying power of hindsight—a power that Domanovic is reluctant to exploit. From yu to me uses several of the standard documentary conventions—the interviews with experts, who sit in front of the camera and talk to someone sitting behind it and to the side, the use of old newsreels and other stock footage—but not its narrative form. The stories it includes don’t add up to a big, cohesive one. Facts about .yu and relationships between them can be more easily extracted from a publication accompanying the video. It has the full transcript of an interview with Jerman-Blažič, and documents such as her email requesting that YUNAC, the Yugoslav academic research network, be connected to the U.S. internet, and a heated exchange about disconnection of Serbia from the internet during civil war.

There are more details about the social spaces around states and domains in From yu to me than there are in Domanović’s collection of websites on international servers, but the video, too, is about conveying impressions of these relations rather than drawing some kind of conclusion about them. From yu to me gives a sense of the office politics and working life around an emerging technology, of the meetings and business trips to far-off places necessary to develop an instrument that connects people, that closes the distance between you and me. Those details flesh out a time before .yu was canceled, dead, preserved in a museum collection, and Domanović wants her account of that time to approximate the openness that people who lived then felt, the unfinished work on .yu when a Yugoslavia with internet still seemed possible.

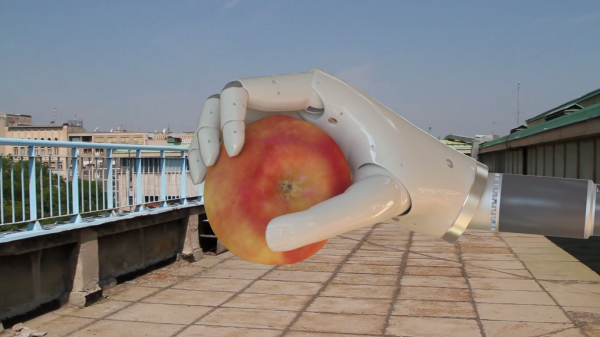

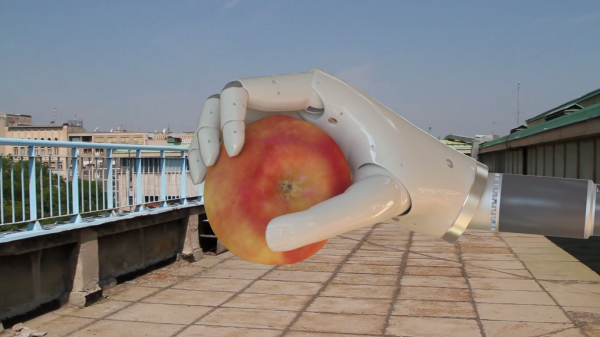

To that end, perhaps, Domanović chose to feature another, unrelated achievement of Yugoslav technology in From yu to me, one that doesn’t have an immediate application to the internet, or anything else—the Belgrade Hand, a robotic arm developed in a lab at University of Belgrade in the 1960s. Domanović included both archival footage of the hand and an animated version that unexpectedly reaches into the screen, first testing the weight of an apple, then feeling its fingertips. A technology that fills the social space between bodies has become commonplace, but one that is a body still seems strange. The distance from you to me may be known but the one from us to it isn’t.” – Rhizome