Superflex

Sunday, 8 April 2012

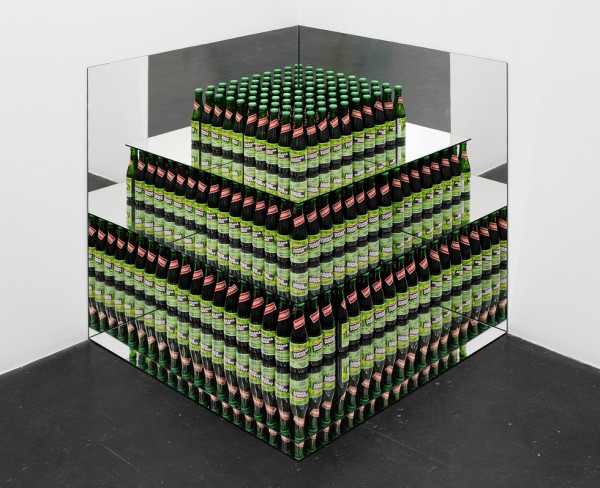

Work from their oeuvre.

“Banks, of course, have rarely been so topical. Names like Northern Rock — the commercial bank that suffered a devastating run as the subprime mortgage crisis emerged in 2007 — and Bear Stearns — the investment bank that collapsed in 2008 — have been prominent in the news. Reportage and op-ed have repeatedly explained economic terms and banking practices that until recently were things I’d barely considered. Nothing in the Karangahape Road branch of the ANZ on the day of Today We Don’t Use The Word Dollars invoked the technicalities of the recent international financial turmoil directly, but they were evoked nonetheless. Simply through bringing the frame of contemporary art into the bank, SUPERFLEX drew special attention to the institution in general, for both staff and art audience.

The effects of SUPERFLEX’s specific intervention are known first and foremost by the ANZ branch’s employees. What is going on is all the less available to an onlooker for the fact that it is something not being done: A contract has been established between the artists and the bank that requires any staff member to pay one dollar to their social fund if she or he uses the word “dollar” during trading hours, 9:00am to 4:30pm today, Wednesday, May 27 2009. The deviation from routine is visually marked — by some crêpe paper streamers, balloons and the tellers’ matching sports shirts — but even this is hard to see from the outside, as it is only on their own initiative that the workers have repurposed these things from their usual significance, celebrating the ANZ’s sponsorship of a national netball competition. The signed contract that establishes the conditions for the day and the tally of forfeits are kept behind the scenes.

The agreeable-sounding “we” in the artwork’s title helps the rules of the temporary ban resemble a party game. To avoid a certain word, though, is often a serious business: to recognise a politics of language. Anti-racist, anticolonial and feminist movements have raised awareness of the significance of what and who gets referred to how in recent decades. Their efforts have shifted our diction, in a process of self-censorship now widely recognised by the pejorative term “political correctness”. For this reason, today’s scenario might suggest the possibility that “dollar” is a dirty word; the fine operating something like a swear jar.

“Dollar” — from Spanish and Dutch uses of the German Thaler — names many currencies including the New Zealand dollar, but is overwhelmingly associated with the United States and its history, and thus with American mythologies of wealth and success. To highlight it in this way points up connections and disconnections between the local here and the USA, that country’s influence on the world’s markets, and the global role of their currency’s aura of capitalist promise and power. It is clear that — along the lines of the possible politics of language — as a unit of value, the dollar has more than a literal weight. By sad coincidence the week before the work, for example, a young, upcoming Atlanta hip hop star had been shot and killed. His name, worn like verbal gold jewellery, was Dolla. On the Wall Street Journal blog ‘Real Time Economics’ (November 6, 2007), Kelly Evans picked up on another journalist, Mark Olson’s observation in The Minnesota Chaska Herald that — right at the beginning of the financial crisis — hip hop maven Jay-Z appeared especially sensitive to the shifting real and status-symbolic value of the US dollar. Seeing the newly released video for his single Blue Magic (featured in the movie American Gangster, starring Denzel Washington (and coincidentally New Zealand-born Russell Crowe)) Olson was quoted as lamenting:

It’s sad that rap stars can no longer show their style with a good old $500 bills (featuring President McKinley) and now need to flash 500 euros (featuring some sort of suspension bridge). I don’t need the chairman of the Federal Reserve to tell me about the state of our economy. I just need Jay-Z, the new Alan Greenspan. I don’t blame Jay-Z. A stack of $50,000 in euros would equal $72,000 in US currency. And you’d need 144 $500 bills to equal a stack of 100 500 euros. I don’t know if even Jay-Z has that large a money clip.

At the same time, hip hoppers joked that “euro” wouldn’t scan as well in lines like the refrain from the Wu Tang Clan’s biggest single, “dolla dolla bill y’all” (C.R.E.A.M., 1993). Despite the fact that there might be many reasons to question the cultural loading of the term “dollar”, the suggestion of irony in SUPERFLEX’s gesture of disciplining a bank’s use of such a central concept is never paid out. The sophistication of the work, perhaps, is that the agreement between the artists and the bank does not result in the sceptical artists having one over the uncritical institution. For one thing, the Branch Manager Lisa Burns can clearly account for the value of the undertaking in her own terms.

Apart from showing neighbourly goodwill to Emma Bugden, the Director of Artspace next door, who is facilitating the work, the break from routine offered some morale-building fun for her team, who also found it interesting to be made aware of what they take for granted in their own behaviour. Although she doesn’t resort to jargon, the undertaking contributes to total quality management.

Being in a bank where I don’t hold an account is slightly awkward. Security have been briefed, and are expecting those of us without obvious business here to drop by the scene of the artwork, but I am reminded nonetheless of waiting outside a queue once in California for my friend and host to make a withdrawal and the twitchiness of the conspicuously armed guard. Being here makes me aware that my sense of other banks comes largely from advertising, and — along with all the smiling couples unpacking boxes in new homes and laughing into cellphones — brings to mind a campaign by another New Zealand bank that made a show of replacing intangible banking clichés with concrete aspirations, another sign that for their own reasons banks are more than up for watching their words.

SUPERFLEX have been extremely formal, though, in establishing a legal contract, differentiating the experience from a training exercise or workshop. The instrument of the contract has a political history. Tracing the structural and cultural connections between capitalism and democracy, Ronald Glassman notes the defining features of trade-capitalism that are conducive to the establishment of democratic rule, including the establishment of contract law as a feature of business transactions, and the extension of it from business law to criminal and eventually constitutional law. 2

A variation on a month-long work, Contract, made with the Royal Danish Theatre in 2007, the work is emblematic of SUPERFLEX’s practice as intermediaries, operating as a business as well as artists, and creating value by circulating ideas and products both within the art system and in other contexts. Sometimes, in this series of contract works, value is created simply through such a translation. The work, then, ultimately gives us pause to consider value, how it is created and described, in art as much as in the world of finance. The artists emphasise in their statement their interest in real relations and concrete effects. In the terms of Brazilian artist Cildo Meireles, they have made an “insertion into an ideological circuit”.3

It is reminiscent of his defacement of actual legal tender, Insertions into Ideological Circuits 2:

Banknote Project, 1970, and perhaps more so his production of a nil currency, Zero Dollar, 1978—1984), that materialises precisely those things in a dollar that exceed its purchasing power. However, if the value of the dollar is unstable in so many ways —between credit and cash, say, between currencies, and between exchange value, cultural capital— the case of art is no less complex. SUPERFLEX’s artwork does nothing if not highlight the blur between real and symbolic effects. Alongside the Rolls Royce and the noteworthy wad of euros in in Jay-Z’s Blue Magic video appear Damien Hirst-like spin paintings and a recognisable recent Takashi Murakami painting, as illustration of the idea that, as Pharrel sings in the chorus, “I ain’t talkin’ about it, I’m livin’ it”.”” –Jon Bywater