Juliette Bonneviot

Wednesday, 26 December 2012

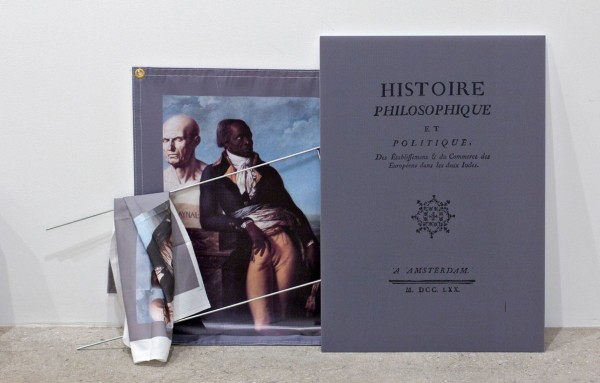

Work from her oeuvre.

“In The Record of the Classification of Old Painters, sixth century Chinese art historian Xie He established the ‘six principles of painting,’ classing artists into six categories. The first was ‘Spiritual Resonance,’ while the final was ‘Transmission by Copying.’ These two poles, and what lay between, hence emerged as a critical factor in both the creation and appreciation of Chinese painting.

‘Transmission by Copying’ refers simultaneously to the circulation of the original as well as a comprehension of the fundamental method of Chinese painting and calligraphy. Xie believed that there was no creativity involved in this category; thus, he demoted it to the sixth and final ranking. However, for those new to the art of painting and calligraphy, it represents the inception of a long journey towards the peak of the pyramid.

Juliette Bonneviot’s ‘gesture’ can be seen as an instance of ‘Transmission by Copying,’ even though she has never taken the ten-plus-hour-long flight to the other side of the world, nor has she heard of Xie He. Her ‘original’ is the Chinese version of the poster of a Hollywood film. The scroll wiggles down from what resembles a ‘typically Oriental’ aluminum arch with clumsy characters, which, strangely enough, are written in the ancient Chinese style of seal script. The red circles and crosses, denoting right and wrong, are copied from Gu Wenda’s Mythos of Lost Dynasties, a pseudo-character series that pointedly expresses appreciation and disapproval. Bonneviot’s writing thus echoes a style of calligraphy that is more than two thousand years old, filtered through the revised ‘copy’ of a contemporary Chinese artist-calligrapher very much steeped in his culture’s aesthetic tradition. And, while Bonneviot is not endeavoring to attain the ‘Spiritual Resonance’ that Xie claimed as the goal for all painting, she instead achieves an intriguing scrutiny of a series of simplified symbols. This unites Bonneviot with the massive degree of ‘Transmission by Copying’ currently taking place in China. The copycatting gadgets imitate not only the appearance but also the brand name of major Western products, revealing the Chinese public’s image of the contemporary lifestyle of luxury – one of the more extreme examples of Bourdieu’s ‘symbolic capital.’ This unprecedented process is also scrutinized by Bonneviot in her ‘gesture,’ wherein mass production is captured through ironic symbols: the sweet ‘candy bar’-shaped music player hanging helplessly alongside the silk and ink. The brand of the player, iRiver, easily recalls the fame of iPod. But, upon further scrutiny, it turns out to be a South Korean product. And so what? It is as far as forever, seven time zones away, and China and Korea are so close to each other. From here, < even I can barely see any difference.

Nevertheless, the soundtrack in those players brings another kind of ‘Spirit’ to the ‘Copying.’ The sound of Chinese instruments and electronic drums showcase a blend of acid rock fused with the exotic. This soundtrack also draws the outline of a comfort zone. It’s mute and undisturbed inside, protected by the boundary of distance and language, and noisy and chaotic outside, stuffed with a nod towards the African continent as well as absurd poetic monologues.

I have a snow globe in my hands, and there’s a tiny little double-roof pavilion inside, as well as a little oriental man in a white garment, standing on one leg, arms held up and balanced on his sides. It is not snow that covers the tiny little ground, but yellow leaves. I shake the globe. From its base, the sound of a bamboo flute being played, while the leaves waving up and falling gradually around the little man reveal and then re-cover the black character written on the red background. I am guessing it reads ‘lucky.’ I stare at the globe. It is China. Almost.” -Li Qi