Theo van Doesburg

Monday, 5 August 2013

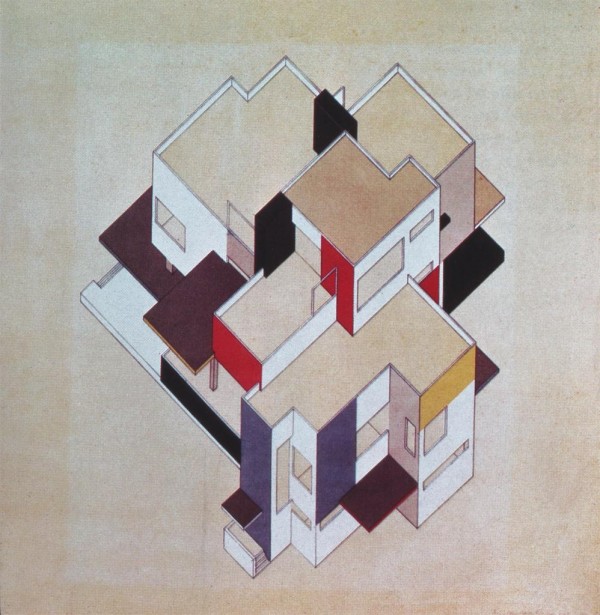

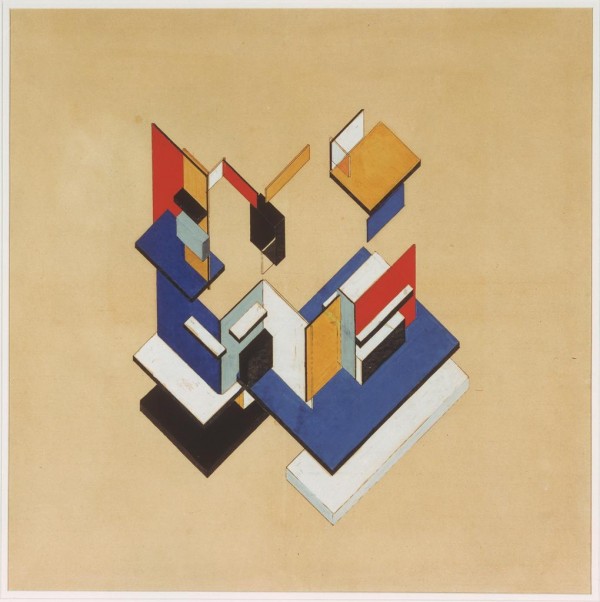

From top to bottom: Still Life (1913), Design for the Central Hall of a University (1923), Maison Particuliere: Axonometric Drawing (1923), and Contra-Construction Project Axonometric (1923)

“Born Christian Emil Küpper in 1883 into an artistic family in Utrecht, he only became “Theo Doesburg” when he started painting – his adopted name being borrowed from his stepfather. The “van” was added later, in much the same way that Ludwig Mies added “van der” when he merged his mother’s maiden name, Rohe, with his own paternal surname. One detects a similar feeling of social insecurity in the two men.

At the start of his career Van Doesburg was a competent figurative painter, his work reminiscent of Van Gogh in early, potato-eater mode; but he soon came in contact with non-figurative painting and in 1916 met Mondrian, newly returned from Paris. The devotion of both men to the creation of a purely abstract art led to the formation of the De Stijl group in 1917 and the publication of its magazine, De Stijl, which Van Doesburg edited and published from its foundation that year until its demise following his early death in 1931.

Van Doesburg’s life may have been short but it was energetic. Throughout the 20s his saturnine features, often topped with a homburg and usually accompanied by a cigarette – think Humphrey Bogart – appear in photographs of divers artistic groups from Paris to Weimar, from Berlin to Zurich and Milan. Neo-plasticism, constructivism, suprematism, dadaism, elementarism – the “isms” of the time are bewildering to anybody but a specialist, but Van Doesburg was involved in all of them. Indeed he invented some. He was both gregarious and eclectic, a centripetal element in a diverse and chaotic artistic world. He lectured and published, talked and theorised, attended conferences and congresses and exhibitions, many of which he organised himself.

Of all the arts that Van Doesburg touched perhaps his greatest influence lay in the area of architecture and design. Together with the architects JJ Oud and Gerrit Rietveld, it was he who took the flat, geometric painting of the De Stijl group and burst it out into the third dimension. Indeed he even tried to inform his work with a fourth dimension, although with what success is a matter of debate. Certainly he was fired with a thrilling spatial imagination. His axonometric projections of ideal houses, created in conjunction with the young architect Cornelis van Eesteren, are crucial in understanding this concept so it is a shame that they do not form part of this otherwise comprehensive exhibition. A plastic model of one of the proposed buildings (the “Maison Particulière”) gives some idea but a 3-D model is not as striking as the original drawings. A model is too literal. In the drawings perspective is ambiguous; walls are no longer supporting structures but floating, intersecting planes of primary colour; rooms are not static boxes but conceptual spaces hovering in the air. The volumes of the buildings seem to explode from an inner core, as though erupting into the third dimension and straining for that elusive fourth.”

-Simon Mawer for The Guardian