Richard Healy

Wednesday, 1 January 2014

Work from Prone Positions

“Oliver Basciano: Your work, which encompasses sculpture, installation and video has this uncanny, unworldly feel to it. This perhaps stems from your use of digital animation in the videos works, which in turn affects how the viewer receives the tangible objects. Yet we should be more familiar with this aesthetic – we spend so much of our time working in ‘digital space’ – on our laptops, staring at our phone screens after all. What is your work’s relation to real world materiality? Much of your work seems a rejection of, or at least a critical investigation, of physicality.

Richard Healy: The idea of ‘materiality’ occupies a lot of my time. For me physicality has always appeared to be the result of ‘hard-work’ or ‘labour’. I would never say that I reject hard work, but I do investigate the idea of how ‘hard’ I am working versus how ‘productive’ I am being in the studio. I suppose this is a by-product of working with digital technology. I can sit until late in the studio being highly productive, creating thousands of high definition jpegs for a new film, however I am not working ‘hard’, my computer is. Again, I can make dozens of marks with a digital pen and in a few clicks these are transposed into chiseled strokes on a slab of marble. The computer allows for this hyper-productivity because it is divorced from the time constraints of physical material labour.

OB: How political is that mediation of labour for you? Marx said we were supposed to become freed through our labour, and then the Silicon Valley utopianists said we’d become freed from labour. Yet we seem to have become enslaved to our screens. I always think of video rendering as a great expression of that: the computer is doing the work, but it traps you, babysitting it. Or, more generally, maybe we’re the babies and the computers are looking after us. But perhaps you have a more optimistic outlook!

RH: Generally I have an optimistic outlook. My interest in labour is a result of the consistency of technology in our everyday lives, every moment is an opportunity to be productive at the hands of a laptop or smart phone. Is that liberating? I honestly do not know, I definitely find the speed of technology liberating, but you are right that more often than not it just frees more time to use more technology. To open another window or look at another screen.

Any political mediation would be on who owns this productive space. I use various online platforms through which I make my work – Tumblr pages, issuu pdfs, Vimeo uploads –these platforms obligate the user into a form of self-design or self-presentation. This is interesting I think. How we are so free with the idea of appropriation that we happily navigate the web projecting images of ourselves through the default settings of others. I realise the speed of the computer screen obligates me to work more, blurring the boundary between social past-time and real-time labour. However my optimistic side hopes that this blurring is a result of my satisfaction with producing work through this process. Not only can you produce effects quickly through a computer but in a second you can upload it onto the web to show the world. The act of courting attention in this way can have its trappings, however I view it as a liberating aspect that the computer screen has offered the art world.

OB: We can never fully reject materiality though, however much we spend our lives working with or within computer space, we’re still eating, breathing, moving objects in the real world.

RH: Yes and the work isn’t rejecting or ignoring that. It will always be rooted in the material world, so undoubtedly the idea of materiality is always present in my work. For example I have a collection of images of marble and other surface textures to render into films and prints. These materials are always placed out of arm’s reach however. They are suggested, described rather than realised. When an object does escape the gravity of the computer screen and I produce a sculpture, the choice of materials (mainly glass) echoes their digital origins. These choices were repeated in my last show where digital prints were mounted directly onto the surface of the glass frames denying any physicality of the paper, while trying to recreate the moment when I first saw the image on the computer screen.

OB: Perhaps a work you made for a show last year titled Vetiver connects that idea. You made candles scented with the smell of a Comme des Garcons cologne right? Whilst the candle is an object, its main function is something immaterial, a smell.

RH: The use of perfume came about from an invitation to do a show at Marian Cramer’s project space in Amsterdam. It is a unique situation, as it demands that the artist make work for Marian Cramer’s home as well as the white-cube gallery space. The notion of this brought up obvious issues of gallery display, interior design and taste. I started to make scented candles as objects that could exist in both spaces and bridge the presentation. The idea of using my cologne in these candles seemed sensible: it allowed the show to address my tastes as the artist and Marian Cramer’s tastes as curator and collector. As a motif it seemed very different to other elements within the show. Most of the works deal with surface and the formulation of architectural space, yet here there was nothing but the heavy vapor of the cologne I used.

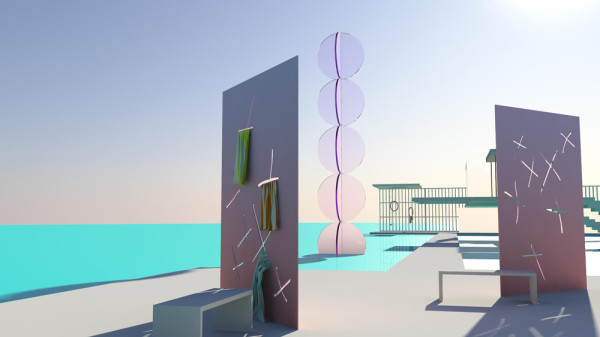

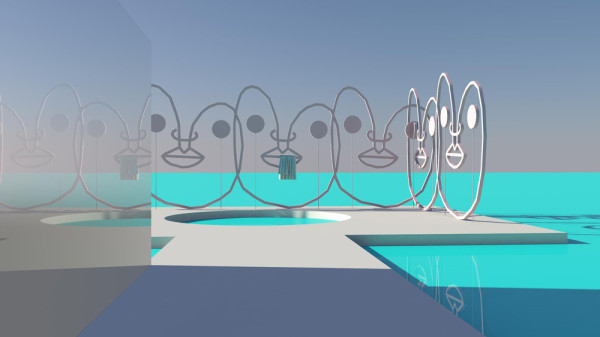

OB: What’s your relationship to design, or more specifically architecture? You didn’t study it did you? Your work, both the videos and the sculptures, has an architectural sensibility to it. The computer animated video Testing Ground for example has this amazing architectural space depicted, yet it’s a fiction – it reminds me of those old Archizoom projects or Zaha Hadid’s conceptual designs.

RH: Yeah, I really like the idea of fiction within art practices, and architecture links to this. I never trained as an architect and when I was younger I didn’t express any interest in architecture, I did however love science fiction. And my first interests in architecture came from sci-fi design – Star Trek: The Next Generation, Babylon 5 and Dune, as well as the Foundation series by Isaac Asimov were hugely influential. However, it wasn’t until I saw an exhibition by Superstudio that I realised that architecture could be concept based, that it could be virtual rather than real. That first encounter with Superstudio lead to me seeking out Archigram and Archizoom and their models, fanzines and masterplan prints. With all these groups, what I liked was the language they used; in fact I probably liked the way that they communicated their ideas more than the ideas themselves. Architectural design has a really great aesthetic to create fiction with. Models and prototypes are such interesting objects of potential that allow you to point the audience in a direction and at the same time afford the audience a lot of freedom.

OB: When did this interest manifest itself as a work though?

RH: The first time I made an architectural film was out of necessity. Part of my fine art course was an interim show of all the student’s works in what was a very small gallery. The idea of compromise in that situation was problematic for me so I decided I would make a virtual model of the gallery and curate a solo show of objects from my studio at the time. That video became the first version of Testing Ground. These videos have been shown several times since that outing and every time are different, reflecting a different set of objects and ideas that are occurring in my studio. In fact I think of Testing Ground as a direct extension of my studio. That is another aspect of architecture that I have borrowed – the idea that a work can be edited, altered and improved in subsequent versions.

OB: That idea of editing, renovation and improvement (which a digital practice lends itself to) is picked up in a text that you made available alongside a show you did last year. It was a story, a parable really, written by the architect Adolf Loos, describing a man who hired in an architect to furnish his house. The essay seems to mock the idea of a ‘finished product’.

RH: Loos’ essay was a critique on a certain mode of modernist design and the limitations it placed on the user. In the story the client wants to bring art into his home, however does not want to deal with choosing it, so hires an architect and defaults to his tastes. I found the idea of scale the most engaging aspect of the essay. In the end the architect has reduced art and design to a capsule collection of good-taste, while simultaneously reducing his client’s life into an ordered trap of certainty and function. In Testing Ground I delay any conclusion, I prolong the process with more edits and additions. It is a space for production without any conclusion, which is an exciting prospect.

Interestingly, having used Loos’ essay I came across Against Nature by the French novelist Joris-Karl Huysmans, that seems to celebrate the provisional and inconclusive. I ended up using an extract to accompany the exhibition Vetiver. In the extract Huysmans’ protagonist creates various perfumes to mask the smell of the garden outside his window. In the end he gives up, collapsing exhausted on his windowsill, but only after having mixed endless variations of compounds and tinctures. The whole book is filled with similar unconcluded projects, however there is something progressive about these willful acts even though they serve no function. It’s a really moving book.”

text via interview Oliver Basciano