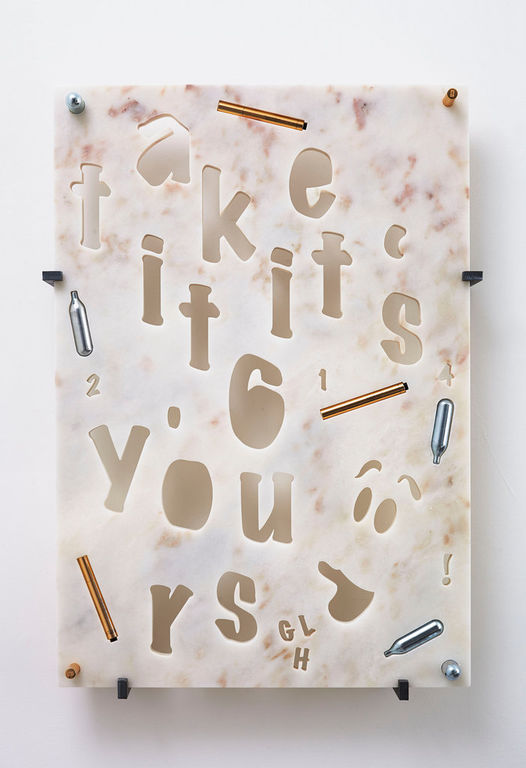

George Henry Longly

Tuesday, 4 March 2014

Work from “Hair Care” at Jonathan Viner, London.

“Whoever thought that Samson’s power would be in his hair? Not Delilah, or anyone else for that matter. A magnificent Biblical warrior, with superhuman powers, Samson tore a lion limb from limb with his bare hands with the help of his magical hair, but without it, he found himself to be utterly average. Hair is primarily an accessorial human feature: a way of wearing identity even on a naked body. It is soft and flexible, yet strong – one strand of human hair, should, according to shampoo commercials, be able to bear the weight of an egg. It is also the part of the human body that is approached most like a sculptural material – shaped with the hands into sculptural weaves, slick wetlooks and power bouffants.

The tradition of magic potions and spells lives on today in the world of beauty products, particularly those that are ascribed with magical properties that promise to revive the body’s fading powers. George Henry Longly’s recent marble sculptures, each of which is a standard size of 160 x 110 x 55 cm, carved with au courant phrases, acronyms and dates, are also regularly inlaid with exactly this type of mythic beauty product. Yves St. Laurent’s iconic make up product Touche Eclat, a golden wand receptacle that contains a ‘touch of light’ for disappearing dark circles around the eyes, appears several times, as does Rogaine, a product that promises to bring back lost hair. These potions work via a combination of materials and faith, and are invested in by those who fear giving up the powers that they draw on from bright skin and thick hair.

The conferring of power and desire onto bodies and objects is a recurring concern in Longly’s latest series of works, a trinity of vitrines, in which softness and liveness is repeatedly turned into permanence. Longly has also transformed a living body into a museum object via a casting process. The intimacy involved in the process of casting an attractive body is subverted by the holding of the resultant cast behind glass, resting on a garment from Issey Miyake’s Pleats Please line in a vitrine that is close to a coffin. As with the artist’s work in marble, the ephemeral is made permanent, encased in loaded materials and displayed. The price we pay, however, is that we are not granted to touch this body: important, powerful objects here are kept away from grubby, lascivious touch of hands and fingers. We can vicariously touch objects such as meteorites and helmets, however, in a second vitrine, via live geckos, who are able to stick to objects via electrostatic attraction, thereby entering into a closer, and more intimate relationship with objects than we can ever hope to have. The third vitrine contains an abstract hangerlike sculpture that Longly created from his sketch of an ancient statue of a hermaphrodite that he saw on a visit to Rome.

Longly’s treatment of materials of levity and those of gravitas is equally reverential, and keeps them away from the clamor and mess of the everyday. However they exist in a reverential space that is somehow half serious. Though we can’t touch anything behind the glass, we can sit on the vitrines like they don’t mean a thing. Reptiles climb over precious objects while sculptures are dressed up with nowhere to go, giving a sense of both the genuine power of self-image, and its vulnerability to vanishing into nothing. ” – Jonathan Viner