Cyprien Gaillard

Saturday, 11 December 2010

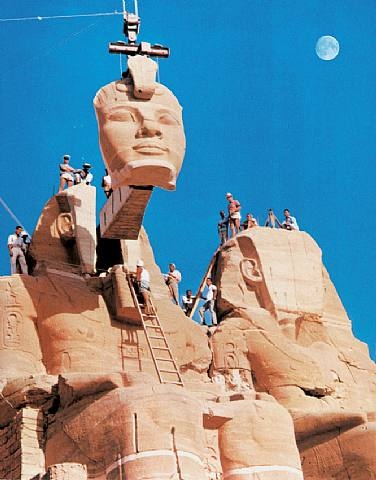

Work from Cairns, Dunepark, The New Picturesque, and one rad sphinx image.

“‘Cairns’ is a series of photographs that depict the aftermath of the demolition of high rise social housing in Glasgow and the Parisian suburbs, shot and printed after Düsseldorf school of photograph’s codes and photographers such as Andreas GURSKY and Thomas STRUTH, while pushing them to their ultimate stage: monumentality, frontality, absence of narration and time reference – ie impossibility to identify the season of the year or the time of the day; but instead of picturing an arrogant modernist building, only remains a pyramid of ruins. As the title of the work suggest, these mounds of rubble resemble Bronze Age cairns – structures erected to mark a burial site and, according to some archaeologists, to ensure that an interred corpse remains underground.

Cyprien Gaillard escavated a bunker which was buried in a hill overlooking the beach of Scheveningen. This is an area already undergoing drastic transformation as the existing communities and industries are displaced to make way for new housing developments. Gaillard’s project comments obliquely on this process of gentrification and the way in which outmoded architecture is buried or hidden beneath new layers of urban development. This work, titled Dunepark – a rough translation of its location – can be seen as the embodiment of the ‘Bunker Archeology’ carried out by the French cultural theorist Paul Virilio in his eponymous 1975 book and exhibition. For Gaillard, the physical process of excavating is a form of negative sculpting. He sees this submerged bunker as a buried readymade. With the help of large earth-moving equipment and volunteers of the Foundation Atlantikwall Museum Scheveningen, Gaillard digged out this massive form to reveal it in all its brutalist glory, before recovering it once more.

In The New Picturesque series (from 2007), Cyprien GAILLARD questions the representation of nature through the notion of ‘picturesque’, literally ‘what is worth being painted’: originally, in the 18th century, rough or rugged landscapes, far from the ‘beautiful’ landscapes the notion later designated. Intervening either with white paint on 18th or 19th century landscape paintings or with torn white paper on old postcards of castles, GAILLARD covers all narrative elements and decorative details, thus revealing their truly ‘picturesque’ quality.” – Budgada & Cargnel