Nanna Starck

Tuesday, 27 March 2012

Work from her oeuvre.

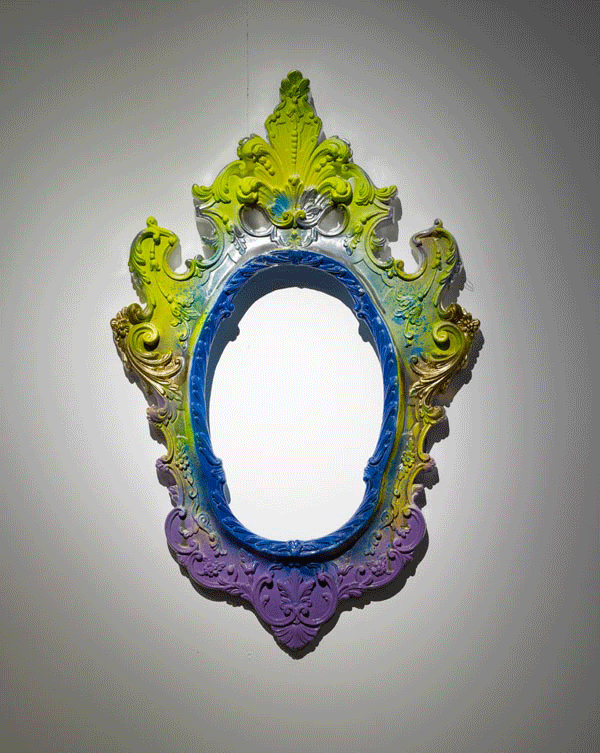

“An empty stage, a picture frame still missing its subject, a pedestal on which nothing is placed. Yet. These are some of the elements in Danish artist Nanna Starck’s sculptural practice. Trained at the cross-media department of Wall & Space at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Art, Starck operates in a media interface between sculpture, installation and painting. Which is what is sometimes hard to determine when you run your eye over her widely branched practice which seems saturated by equal parts burlesque parody, baroque ornamentation and severe formalism. A recurrent element, however, is the modified ‘ready-made.’ Rather than chipping the shape from the block or modelling the figure with her own hands, Nanna Starck borrows objects from popular culture’s archives of kitsch, which she modifies and places in the space of high culture. Take, for example, the decorated plastic chandeliers, that are meant to resemble the old Venetian kind, but that scream out their falseness, enhanced by the colourful, fluttering ribbons, the artist has added. Or take the whinnying horses’ heads that have been retouched in harsh, fluorescent colours in a dripping airbrush style of painting, that hint at the romanticising posters of horses in teenage bedrooms of the 1980s. Beneath the paint, the horses’ heads, available by mail order, are white and plaster and probably intended by the manufacturer a rather different, pure style than they are given here.

The undermining gesture that the modification signifies is characteristic of Nanna Starck’s practice. It is within the paraphrasing reworking of existing material – in the case of the horses’ heads and the chandeliers even materials that are already trying to be something they are not – that a new object arises. In that sense, Nanna Starck is more modifier than sculptor in a traditional sense, as her artistic devices are conceptually founded in the parasitic logic of the ready-made. Existing materials are used and reused tactically and shiftingly.

Voliére LeWitt is the title of one of Nanna Starck’s pieces: a small table with tortuous legs on which has been placed a Sol LeWitt-like construction, which with its rectangular grid seems like too strange a bird on the baroque piece of furniture. In this collocation of minimalism and baroque, the two poles that Nanna Starck’s own practice oscillates between are linked. On the one hand the idiom of the baroque: the superfluous ornament of the paint, the tassels, the whinnying horses. On the other hand a modernist aesthetics: the formal severity, the pursuit of repetition, the use of bright colours and primary shapes such as the cube, the circle and the triangle. As in Voliére LeWitt both poles are often present in the same piece. This is a crucial point, as it is this contradictory dialogue between baroque and modernism that creates the aesthetic ambiguity or tension if you will, in Nanna Starck’s practice. The burlesque is admissible here, but only because it is always carefully controlled. The ornament is fostered here, but only because it is never left to grow wild, rather it is tamed within an immensely tight frame formally speaking.

This control can be viewed as a conscious staging strategy. You could call it the staging of ornament in so far as the ornament is consciously projected as exactly that: ornament. Staging as strategy is central in Starck’s practice. Recall the empty stage, the empty frame, the empty pedestal. The stage and the pedestal are part of Starck’s contribution to the 2004 ‘Exit exhibition’, called The Nothing Award. As props for a performance that has not yet begun, the empty stage solicits a future action. It is the frame around what could happen. The frame around the space of potential, just waiting to be filled up.

The empty stage is also interesting because instead of being a background for a performance it becomes an object in its own right. Robbed of lines, actors and action, the stage enters into a loop of self-reference in which it only points back at itself. Like the empty picture frame, by the way, that only shows the actual framing – not the framed which is absent. Both stage and picture frame travel into a vacuum of significance, a loop of self-reference, which self-consciously bears the exhibition situation itself as both form and content.

You could call The Nothing Award a meta-piece, as it stages its own exhibition in a both intelligent and humorous way. As it shifts the piece from the piece itself to the piece-around: the context of its own presentation. Or you could call it an anti-sculpture, as it, with its empty pedestals, shows not only how today, sculpture has slinked down from the pedestal, but far more radically, how it has made sculpture of the pedestal itself. ” – Camilla Jalving, PhD