Peter Alexander

Monday, 12 November 2012

Work from his oeuvre.

“…I look out from a Cycladic perch on the isle of Syros at a hillside sparsely populated by whitewashed rectilinear geometries, made more austere by the undulating topography. The same perch from which the quintessential maximalist, Martin Kippenberger, once gazed. But that’s another story…The Greeks are consummate minimalists, their white palette chosen to reflect Mediterranean light. Our story is about a group of artists who strove not to reflect light but to “personify” it.

Now quickly moving to a different coastline: that of Southern California circa 1965, where a group of artists waged a quiet revolution of luminosity, using every conceivable method to capture the light veiled in the stunning haze of toxins that created Los Angeles’s radioactive glow. Unlike their brethren on the East Coast—Judd, Andre, Flavin—they were not waging an art-historical battle or burning the flags of Abstract Expressionism or Pop art. They abandoned the vocabulary of representation, removing all but the most elemental forms. Pioneers of Minimalism, they took “sculpture,” already a means of expression that forsook illusionistic space by occupying three-dimensions, to extremes, creating works that removed all but the most indispensable elements of our visual world; light, space, and form, the latter being a residual byproduct of the former two, and itself an element that certain members of this group strove to expunge. In this abyss, the viewer’s optical sense becomes hyper-acute, emptiness now vast fissures of details, the slightest change a traumatic tectonic shift.

These Southern California artists ultimately employed two artistic strategies: according to Robert Irwin, one of their generals, there were “those that were creating within the picture-frame and those creating outside of it.” The group that became known as Light and Space attempted to harness the gases of light and space without traces of a frame. Its key members include Irwin, James Turrell, Doug Wheeler, and Mary Corse. The other group, known as the Finish Fetishists, captured and exploited the phenomenological effects of these elements within the confines of their fetishistic objects (frames). They did not fetishize the object, regarding the vehicle as just the vessel harnessing the magic. The group’s members include Peter Alexander, Larry Bell, John McCracken, DeWain Valentine, and Craig Kauffman. They were unified by their ambitious experiments with industrial materials that had never been used in the practice of making art. The aesthetic dialogue that both camps engaged in resulted in work of uncanny beauty and originality.

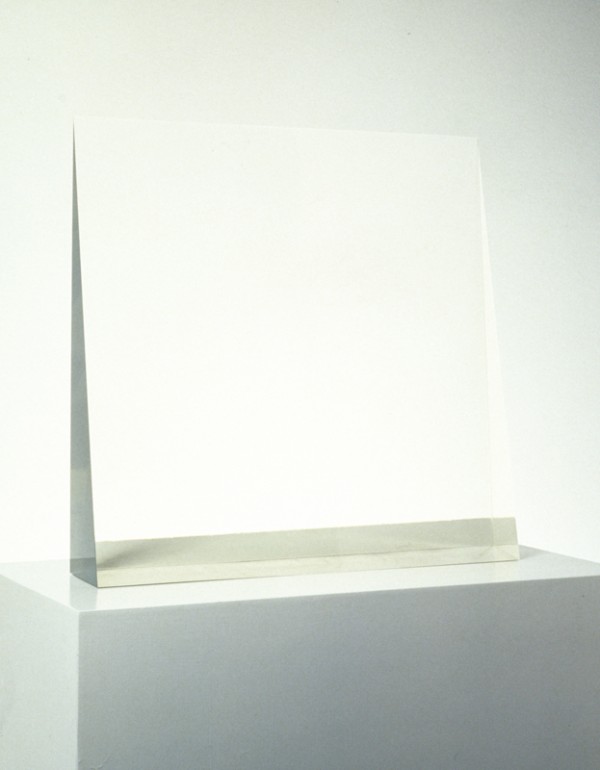

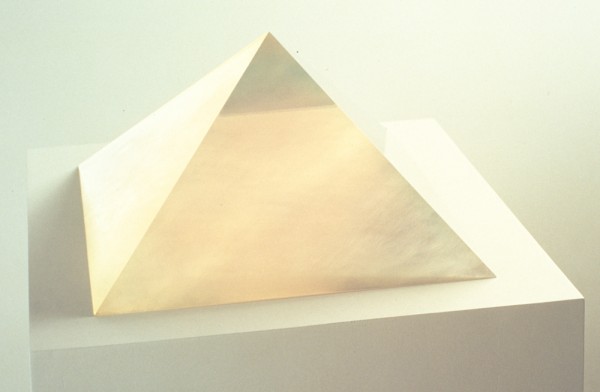

As a young man, Peter Alexander worked for the architect Richard Neutra. Alexander’s architectural foundation, especially the unadorned intersection of planes of glass, is a seminal visual reference in his work. As legend has it, though, his eureka moment came from the observation of the translucence of a Dixie cup when a circular disk of the dried resin used in surfboards was placed at its bottom. Between 1965 and 1972, he forged works by pouring polyester resin into handmade wooden molds. The works appear to hover above their pedestals, like painting in space, or vibrating on the wall. The “frame,” as Irwin calls it, was a barely perceptible structure, a humble artifact from the wooden mold used to create the form.

Alexander’s cubes, wedges, freestanding structures, and the final group of works from this period—bars mounted on the wall—freeze and refract light tantamount to the visual experience of swimming underwater. The process involved injecting pigment in layers as the resin dried, sometimes creating the effect of cubes within cubes (rooms within rooms) or subdivisions of the sculptures (as in Pink-Blue Cube, 1967). At other times, particularly with the more monumental freestanding works, observation from one particular angle, for example the narrow fin of Blue Wedge, 1970 (fig.1) paints a “zip” in space; the background wall “becomes the field of Barnett Newman’s canvas (fig.3). It is the depth of the side view, the experience of looking through eighteen inches of pigment-infused resin, that massages the viewer’s retina, playing tricks on the quixotic brain. Meanwhile, a front view offers a totally different optical encounter, conjuring up the spatial infinitude of Brancusi’s bronze Bird in Space, 1923 (fig.2) the space around the sculpture sharing equal weight with the sculpture itself. The casting was an experimental process that achieved results that were wholly unique from piece to piece and differed from any art making that had preceded it. While the literal gesture was removed from the object, the subtle expression that was achieved from “happy accidents” injected the works with soul that a perfected, machinated process would have slaughtered.” – via artnet.