Soft Intensities

Work by Rachel de Joode, Jaakko Pallasvuo and Yannick Val Gesto at Gloria Knight

“Recent developments in contemporary art frequently beg the question of what to do with art’s materiality. With an exponential increase in the flexibility of the artwork to move between material and immaterial states—for instance, a work that starts life as a digital file is made into a physical form only to be redigitised and circulated online as installation shots—it is clear that an artwork’s iteration in physical space is but one component of a constellation of social, cultural, institutional, technological, phenomenological and affective relations, the exact contours of which are often obscure to the individual.

Soft Intensities takes as its starting point the idea that a reexamination of materiality cannot take place without accounting for the networks that are now, and in fact have always been, inextricably part of material objects. It proposes a malleable space in which the distinctions between an artwork’s material and immaterial components are muddied and confused. Having already witnessed the dematerialisation and dispersion of ‘the image object post-internet’ across its networks of distribution, from this space of indeterminacy new forms of materiality emerge.

Soft Intensities takes as a particular point of departure philosopher Timothy Morton’s recently developed notion of the ‘hyperobject.’ For Morton, these are entities such as global warming or the internet, “things that are massively distributed in space and time relative to humans.” As such, they constitute a loss of critical distance. Unable to be apprehended as a discrete, temporally-bounded entity, hyperobjects are only detectable in their effects, in the interrelationships they produce between objects and their aesthetic properties. Like the contemporary art object, hyperobjects are simultaneously there but not-there, wavering between immediate, tangible effects and modes of distribution that are more often than not hidden from view.

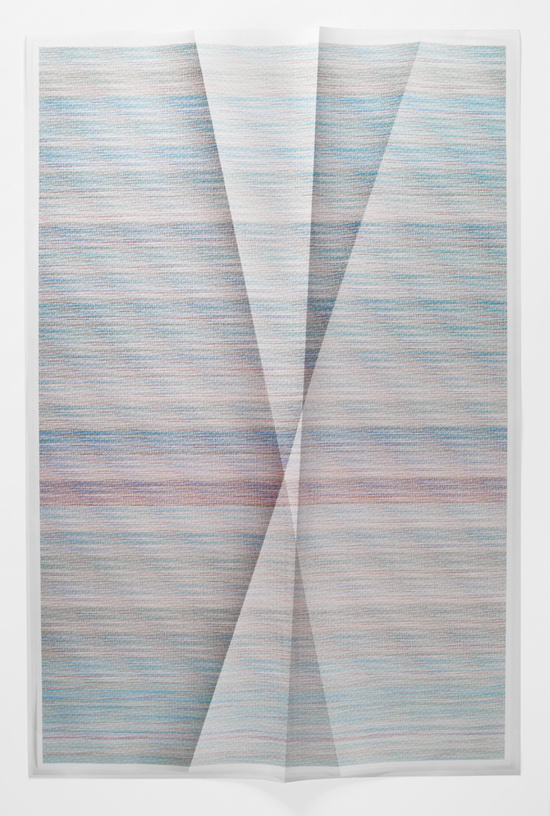

The work of Berlin based artist Rachel de Joode is concerned at a fundamental level with interactions between form and matter. Often working with highly abstracted or ‘raw’ materials, de Joode instigates shifts in form, so that the final art object is frequently one, two or more steps removed from the material being depicted. For instance, a recent work of hers takes photographs of the artist’s own tears which are mounted onto plaster, cut into the shape of their path down her cheek and displayed as sculpture. These shifts in form are frequently complicated by uncanny intrusions of art display practices, as in de Joode’s collaboration with Kate Steciw, Open for Business, which includes framed works embedded in a central plinth and plaster seeming to drip out of another framed, wall mounted print.

Her work for Soft Intensities, ‘Puddle in Pedestal, There,’ exhibits a similar interest in the slippage between material and form, with material this time being understood at its most simple and generative. Consisting of a framed photographic print of a mysterious wet matter inserted into a plain white plinth, the image is abstract and ephemeral. Its flesh coloured tone suggests skin or some kind of rash, but it’s difficult to say with any certainty. Instead, the image evokes a kind of ‘precarious slime’4 whose abstract fleshiness stands in for the status of matter or life itself. The work’s pedestal becomes foundational in the same way. Often spurned as an old-fashioned or hackneyed method of display, its simplicity is the starting point for display, as matter is the starting point for life.

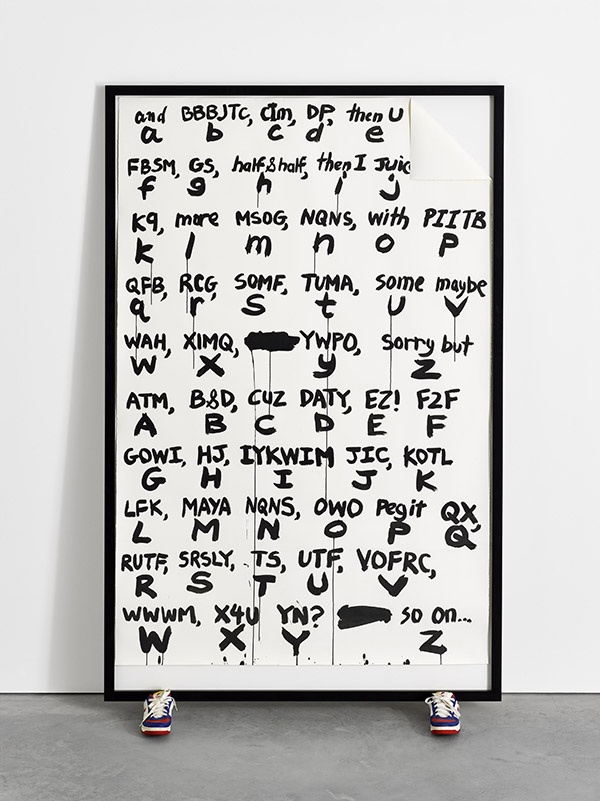

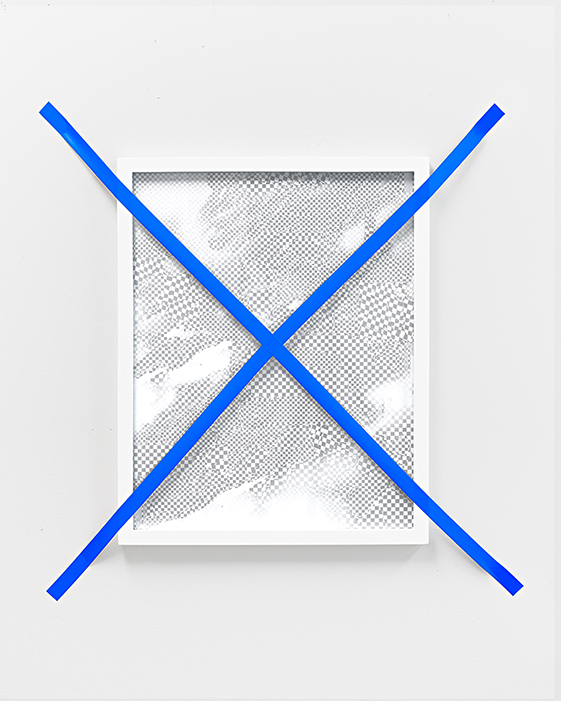

Jaakko Pallasvuo contributes two works to Soft Intensities. 2012’s ‘The Artist’s Statement’ video is displayed alongside a new printed shower curtain work, ‘I Was The One Who Told Snoopy About That Mindfulness App.’ With an art practice that comprises video, drawing, an ongoing series of digital paintings and writing, among other mediums. Pallasvuo’s work displays a repeated concern with how the individual navigates today’s hyper-connected art world.

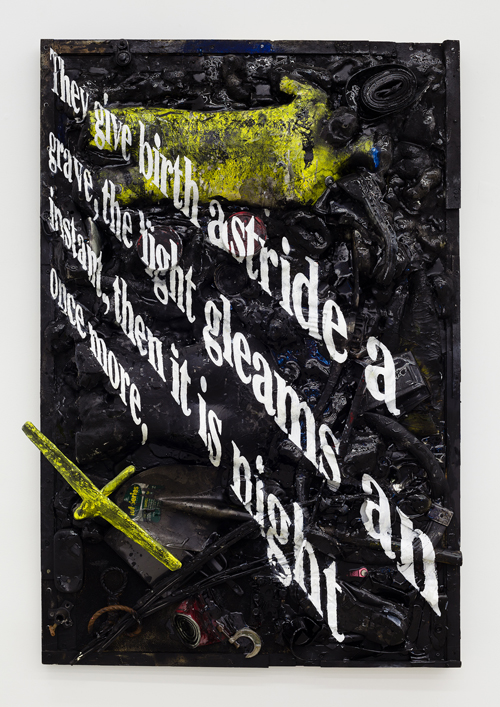

‘The Artist’s Statement’ disparages the tired trope referred to in the work’s title, while strategically positioning it for a new media/post-internet art audience—in the video, a shirtless man drinking Jim Beam reads out excerpts from Rhizome artist profiles and from the Patty Hearst kidnap tapes, while someone smooshes ice cream onto to floor with their sandal covered feet. Messy materiality meets meta-critical cynicism.

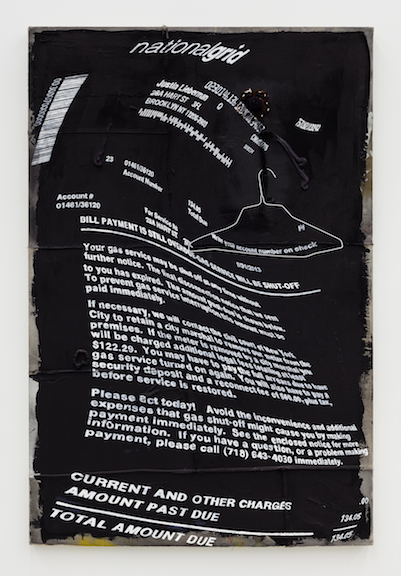

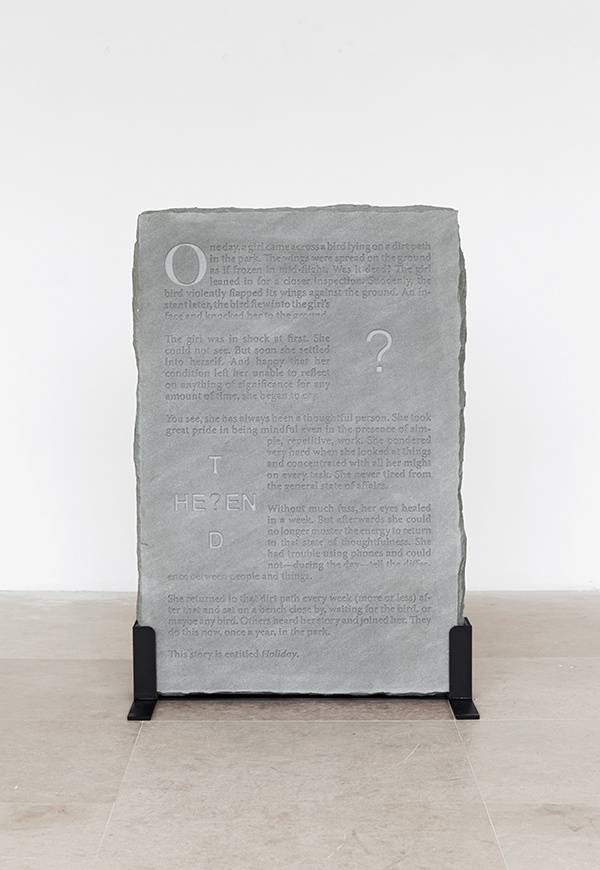

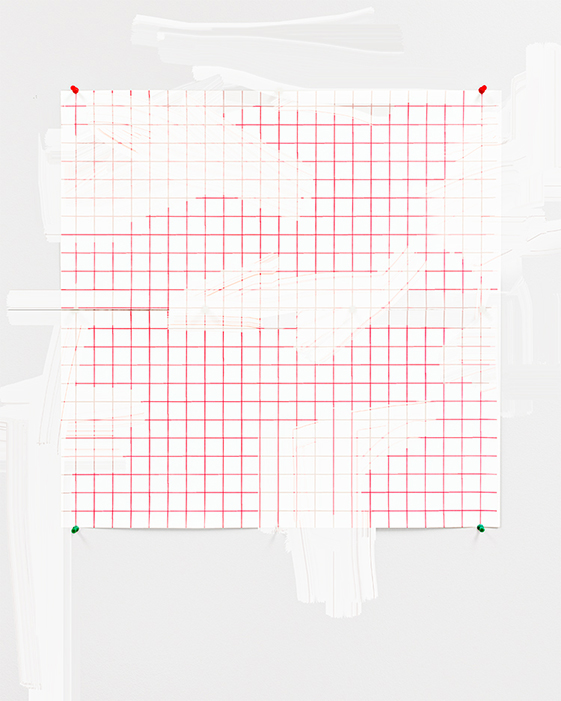

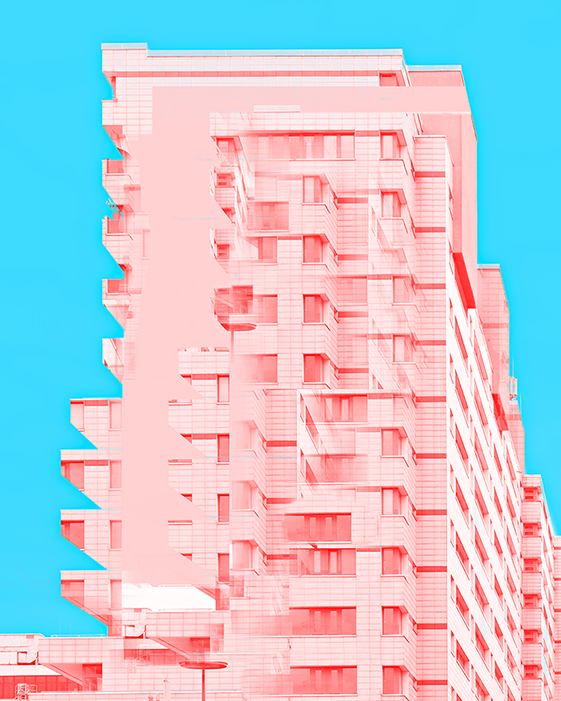

‘I Was The One Who Told Snoopy About That Mindfulness App’ is the latest in a series of Snoopy themed shower curtain works that Pallasvuo describes as “a forced meme.” Featuring text outlining contemporary art cliches, a contemporary installation show and a blurred out image of Snoopy, the work points towards the systems of value and prestige that run the art world, cynically buying into them at the same time that it undermines them. It’s also, as the text on the work explains, something to hide behind. Pallasvuo’s interest in Snoopy stems from he/she/it’s “chill energy.” Snoopy becomes a vehicle for recalibrating the demands of a precarious, hyper-anxious art system, a symbol for soft gestures within vast networks. Yannick Val Gesto’s work has typically borrowed from the vernacular graphic languages of cyber and video game culture. His ‘YuYu’ series consists of four plexiglas works based on compositions taken from screenshots of the anime show Hunter x Hunter. These images have been reinterpreted, fed through different types of software and rendered in garish, nightmarish colours. While traces of its source style remain, very little is left to contextualise them. There is a tension between the digitalised, depersonalised nature of these works’ provenance and their raw, almost organic abstraction. They depict a kind of grotesque synthesis, the paradoxical locating of emotion in cybernetics.” –Tim Gentles