Michael Krebber

Work from his oeuvre.

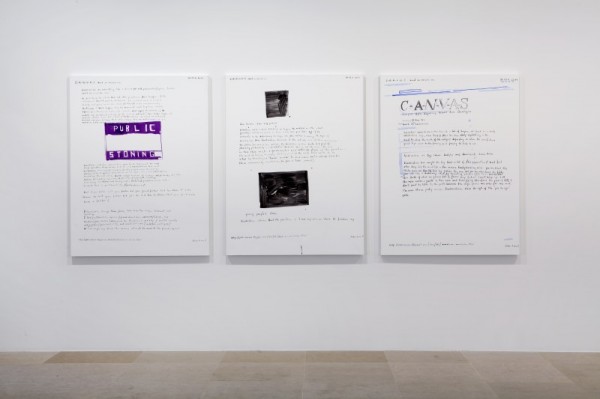

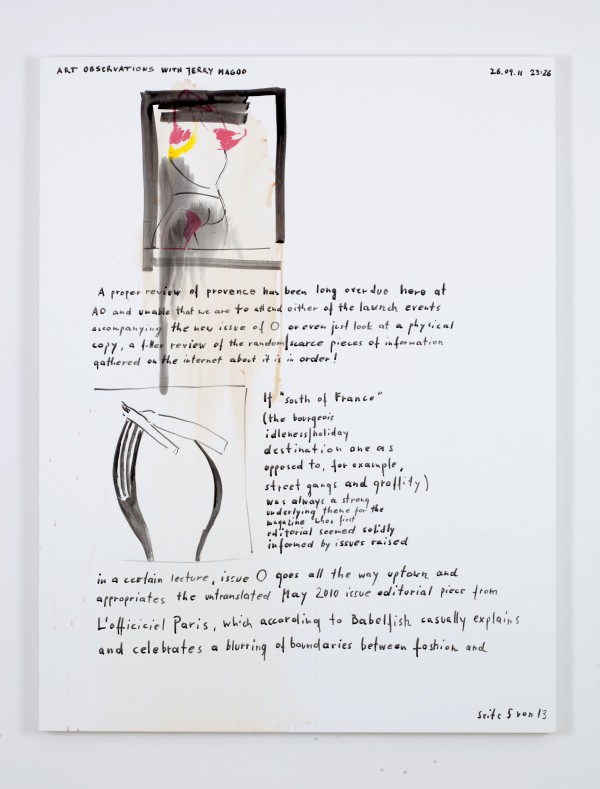

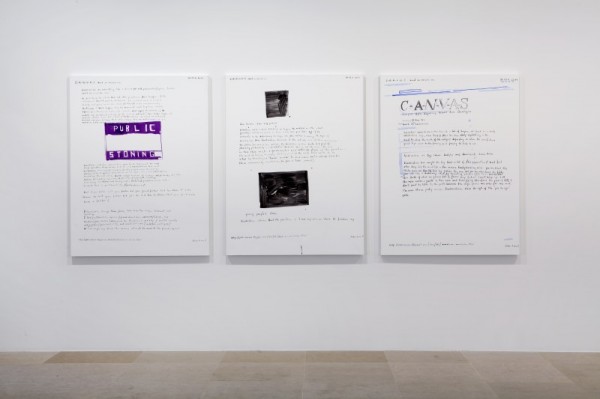

“‘Real art has the capacity to make us nervous’, writes Susan Sontag in her essay ‘Against Interpretation’ (1966), and this is exactly what one can expect when encountering Michael Krebber’s work. In his exhibition ‘London Condom’ at Maureen Paley 21 canvases of equal size depict extracts from Krebber’s recent lecture ‘Puberty in Painting’. The series was realized by a professional signwriter on top of black and white screen prints based on French Western comics. There are energetic cowboys, romantic embraces and a thoughtful-looking, lonesome hero whose image and speech-bubble thoughts are covered by random excerpts from the lecture. These include lines such as ‘painting is such a wonderful little subject, such an exciting subject’ and ‘the wonderful photos in the Feldmann exhibition’.

‘London Condom’ is the final instalment of three shows featuring this new series of works by the artist, recently shown at Daniel Buchholz, Cologne, under the title ‘Respekt Frischlinge’ (Respect Fledglings) and at Chantal Crousel, Paris, as ‘Je suis la chaise’ (I Am the Chair). Each of the exhibitions included a different selection from the 90 canvases that comprise the series. By using different titles in the countries’ native languages for each show, Krebber imposed a certain autonomy on each of the exhibitions, as well as creating a superficial local connection. However, rather than taking up the subject of the works, the titles added to the exhibitions’ complexity and reflected Krebber’s idiosyncratic humour.

Although the works in this series are reminiscent of John Baldessari’s text paintings from the 1960s, as well as of Pop art’s appropriations of comic strips, Krebber is explicitly interested neither in the ironic self-referentiality of text as image nor in the mechanical reproduction of popular culture’s flat imagery. The similarities exist only on a formal level. This kind of referencing has always played a significant role in Krebber’s artistic practice – in the past he has turned Georg Baselitz-esque paintings on their head or used, like Sigmar Polke, kitsch fabrics as canvases.

The starting-point for Krebber’s series was his lecture on painting, However, once the words reach the canvas, their meaning changes. A shift from content to form takes place, and the text begins to function as a ready-made. Graphically strong, it merges uncomfortably with the seemingly random selection of repetitive comic-strip imagery. Grainy, dark and partially cut off at the edges, the screen prints are reminiscent of cheap photocopies and render the text fragments almost illegible in places. In their state of painterly vagueness, the works echo the lecture, in which he stated that painting is something ‘which is just undefined and wholly contradictory in itself’.

The press release, which discusses the Hollywood Western Red River (1948), was written by fellow artist John Kelsey. The text takes up the Western theme of the exhibition, but rather than relating explicitly to the images on display, Kelsey’s writing provides another layer of meaning. Red River’s Howard Hawks and John Wayne are described as bossy and macho pals, while Montgomery Clift, whose image is shown on the invitation card for ‘London Condom’, comes across as an outsider and a greenhorn in the film industry. This Hollywood scenario leads back to Krebber, who takes on the role of ‘the lonesome cowboy’ amid the ‘stampede’ that is the art market. ‘Like painting, cattle must be driven to the market,’ Kelsey writes. However, Krebber is anything but new to the art world, and Kelsey’s text makes it clear that Krebber is very much aware of his market clout.

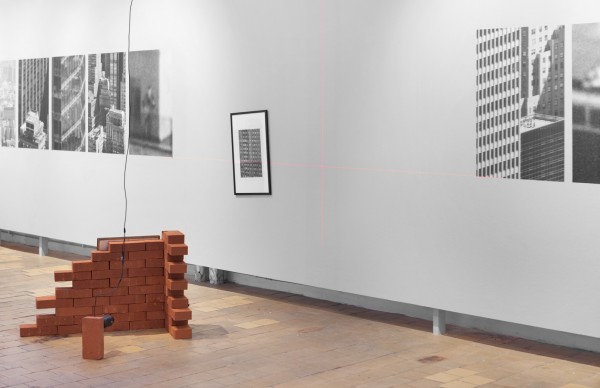

With his deliberate avoidance of a signature style, Krebber is not an artist who is eager to please. In the past he has exhibited a Laurel and Hardy postcard, canvases made from cheetah-patterned fabric and paintings that were partially covered by exhibition posters. Unlike the current series, some of the artist’s previous works have shown traces of his physical involvement. In his exhibition at the Secession, Vienna, in 2005 the impressively sized main space was left almost empty, displaying only a small number of works; earlier exhibitions showed barely anything at all. The context of the gallery space, in particular the formal relationship between the work and its immediate surroundings, is crucial to Krebber’s artistic practice. In ‘London Condom’ he grouped the canvases into clusters of three, four or six, enclosing one of the corners of the gallery wall. In a show at Greene Naftali, New York, in 2003 his paintings were leaning against the wall, while at the Secession the works were framed and hung, conventionally, at eye-level. Krebber shows that the wall is the logical extension of the painting’s surface and that painting is therefore intrinsically linked with exploring its own environment.

The ‘London Condom’ works are characterized by a visual indecisiveness, However, with its system of loose connections as well as what Kelsey called Krebber’s ‘empty appropriations’ of recent art history, this exhibition was a clear reflection of the artist’s understanding of painting.” – Bettina Brunner

![]() Zeidler

Zeidler