Aaron Garber-Maikovska

Work from “Being One and Then Sum“.

““Chopin’s small forms (nocturne, impromptu, waltz, mazurka, scherzo, ballade, prelude) are rooms, single-occupancy, open to hauntings.

Chopin assists my quest to imagine a vocation of pleasure, and to find value in the tiny, the out-of-date, and the wrong.”

– Wayne Kostenbaum: Hotel Theory, Brooklyn, 2007

“Words bounce. Words, if you let them, will do what they want to do and what they have to do.”

– Anne Carson, Autobiography of Red, New York, 2013

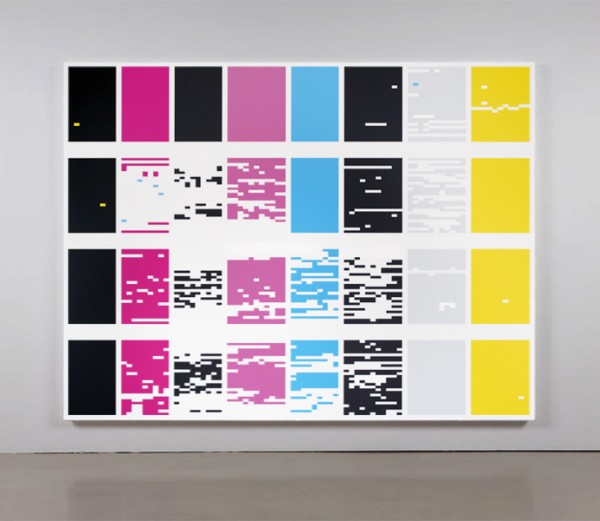

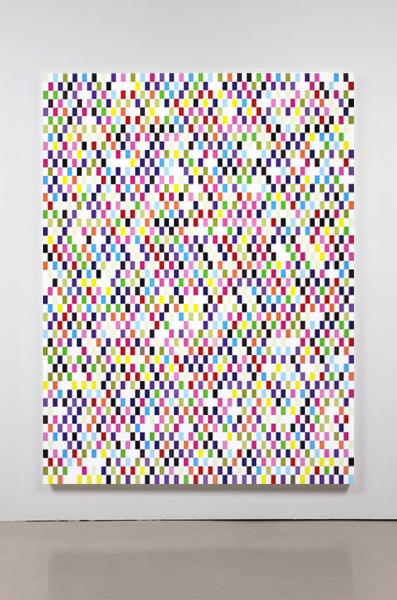

Think of a colour. It could be any colour (I am thinking about breakfast and hence thinking of the yellow of egg yolk, but that is insignificant; you’re free to choose something else). Think of just the colour itself: its hue, its vibrancy and its depth. Then think of a line that makes enough curves to give this an appearance of a face. Then think of another line that is trying to cross and cancel that out. Then think of a third line that is annoyingly close to being a letter without being one. Then think of all of these things at the same time.

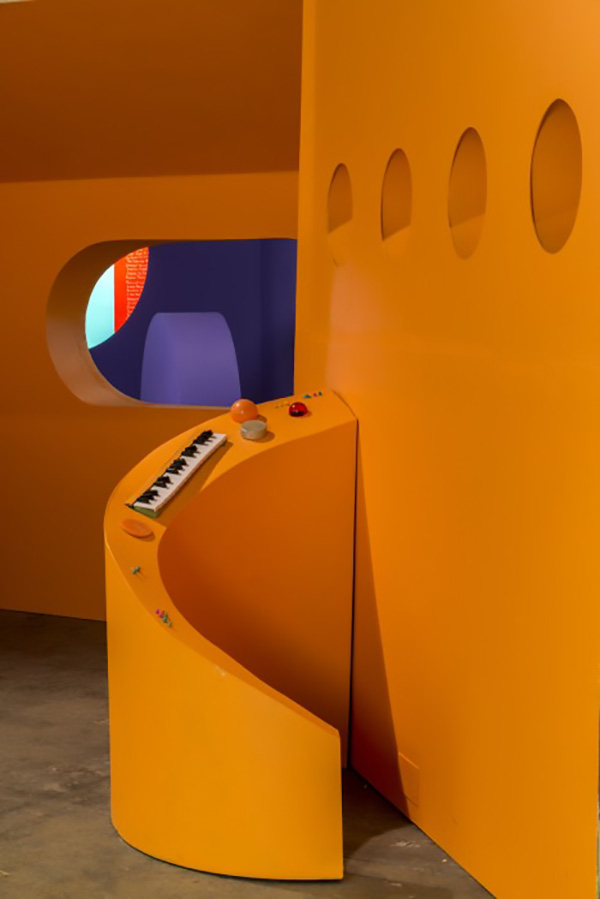

I am trying, but my concentration is poor. I am traveling. I am sitting at the desk in my hotel room. It is too small, even after I have put all of the brochures, the hotel stationery, and the various glossy cards to greet me in the drawer. I have turned off CNN. I have tidied the room. I have put the “Do Not Disturb” sign on my door knob. Yet, I am too painfully aware of this being a place of not belonging and of not working. “The nature of a hotel room, uniform, can´t be determined by its occupant”, as claimed by Wayne Kostenbaum. “The hotel room’s fixed structure enforces the inhabitant’s passivity.” Like the minibar itself it is a place of minimum needs and maximum compromises. And, to make matters even worse, I just leafed through the weekend edition of the New York Times and ended up reading an article in T Magazine about writers and the rooms where they do their work. The imperfections of this interior are even further exposed. “I spend much of my time gazing out of the window of any writing space I have inhabited”, says Joyce Carol Oates and turns away from her Macbook to face the photographer for the portrait shot. There is snow on the trees outside her window. There is a restaurant named “Big China” facing my window.

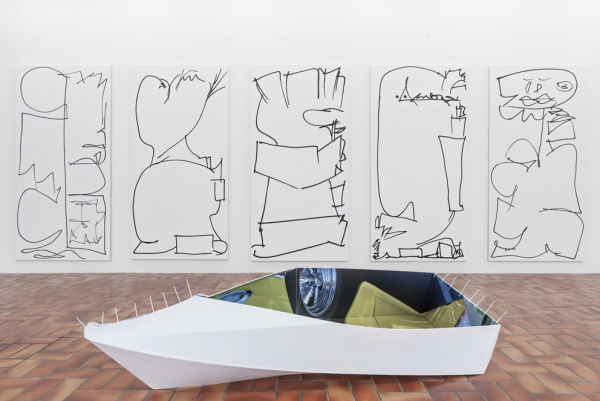

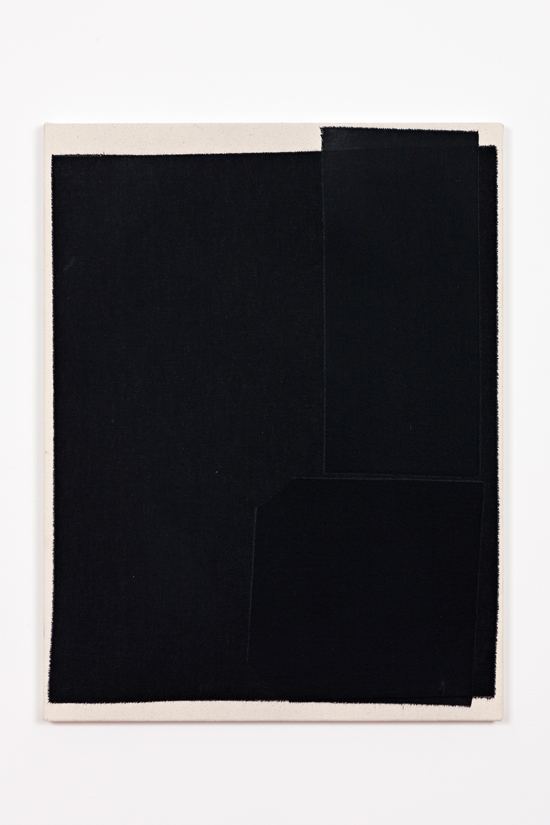

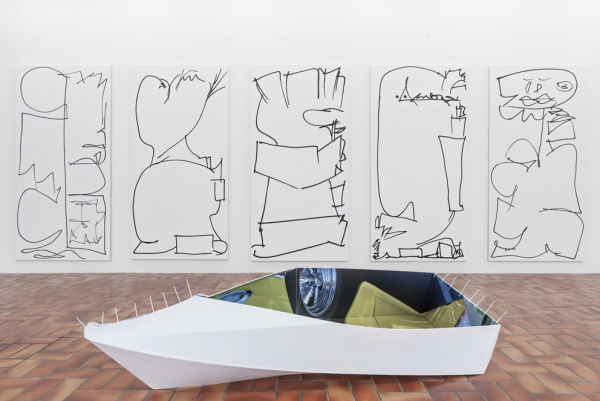

I draw the curtains and think that not only am I missing a view, but that I am also missing a view of the works that I am supposed to write about. Instead there is a framed print of a sailboat above my desk. It is in the middle of Germany. Both me and the sailboat are a tad too far from home. I imagine that a work of Aaron Garber-Maikovska would not only help me here but make good companionship in any room intended for writing – that and a view. He equally lacks the latter (his studio has skylights), but faces the opposite problem when it comes to the former: there are too many of these works keeping him company. His most recent group of paintings – executed in ink and pastel on gator boards – so easily smear with contact, and it is not possible to store them or stack them unless you frame them. Hence, they are all present, and like an audition line for a TV talent show, they wrap around one corner after the other with various degrees of hope and signs of artistic ability. With this constant confrontation of the many stages the series has moved through and assurance in the words by Bruce Nauman – that “An awareness of yourself, comes from a certain amount of activity” – Aaron Garber-Maikovska attempts to move further. Always restarting same way: upper left corner; lower left corner; switch off the GPS (read the traffic and terrain); make it back to the top of the board and its upper right corner. The ink seeping into the gator board, leaving a faint line but enough of trace evidence.

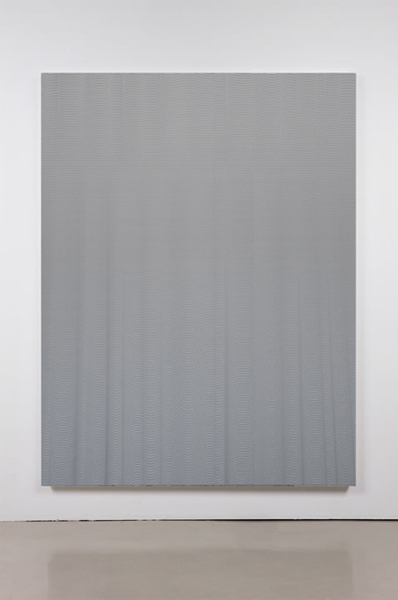

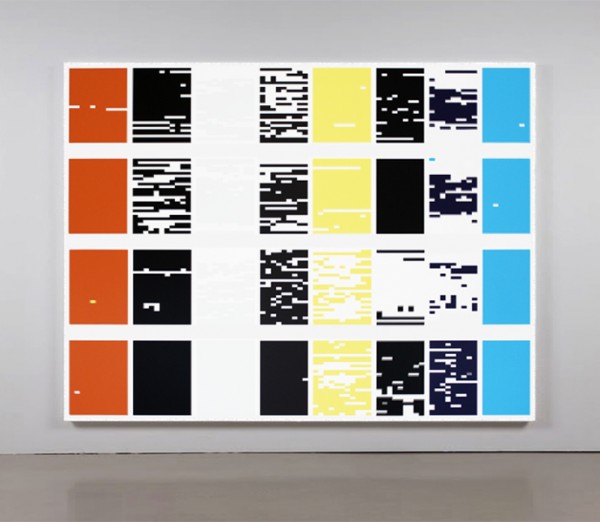

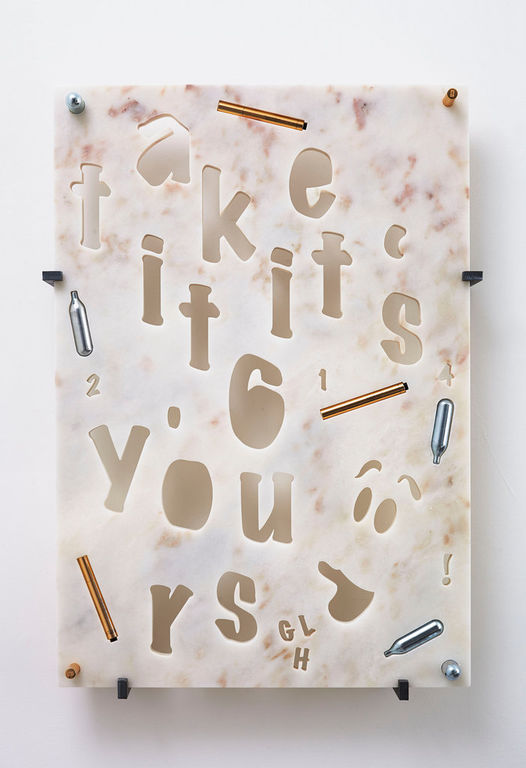

Garber-Maikovska’s movements are both utterly mechanical and unavoidably meaningful. As inane as these paintings might appear, any attempts at gestural abstraction inevitably invites an investigation of meaning and possibly also an exhaustion of such. Doubling in terms of gesture, Garber-Maikovska applies pastel on top colours of the ink in his paintings. Even in the cases where he is using the ink lines to trace his colours the consequence is a dissonant layering, a certain stumble, stutter or desynchronization. The pastel is rubbed out and another layer of ink and pastel goes on top; further adding in terms of rhythm and repetition, and once again fading in and out of sync. This switching between syncopation and in-syncopation brings to mind the modulation and movement of his performance-based video works and earlier text-based works. The former – this exhibition contains three recent videos: “Target Tree”, “Cabazon” and “Fast Red Robin” – sees the artist engaged in a semaphore of movement and a mapping out of the interior where the film is shot. The other works would have him flex, fold and force an abstraction of language. As would be the case in the work from 2009, “Always Quoting Emily Dickinson”, where the title is the very same set of words uttered over and over again. Each repetition is seeking to find its own pace and pitch while nevertheless stating the same, until the words and the viewer are equally exhausted and language turns liquid. As pointed out by curator Catherine Taft: “by riffing on the rhythms and textures of words, he is able to slacken their meanings, test their parameters and unhinge them from our more concrete systems of exchange.” Or, as stated by Jan Tumlir: “No particular urge to make effects that might otherwise predominate. No particular urge to make oneself understood or, conversely, to thwart understanding drives this work; rather, the point is to suspend any such readings on our part in favor of accessing language in a state of emergence.” Possibly taking shape of a letter, a sign, a portrait, a cartoon strip, or as calligraphy, these paintings end up resembling the form and function of the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs where a stylized picture of an object could equally represent a word, syllable, or sound. Like the minibar being both the symptom, solution and surrender, they all collapse in one. On my way out I notice that the wall across the corridor has two of the same framed sailboat prints stacked on top of each other. They are heading in different directions; even the draft of the hotel corridor got it wrong.” – STANDARD (Oslo)