Tabor Robak

Work from Next-Gen Open Beta @ Team

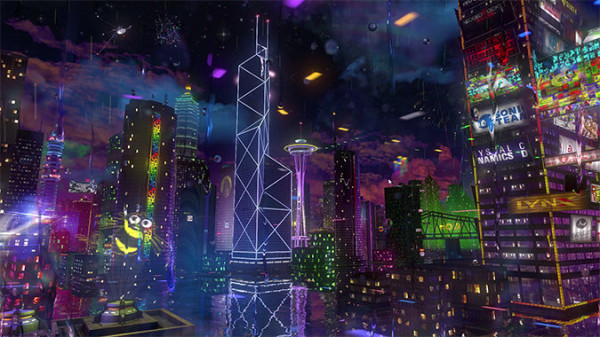

“Tabor Robak’s work employs computer generated imaging to create videos of invented worlds. Working in programs including Unity, After Effects, Photoshop and Cinema 4D, the artist explores a secondary, digital reality, rendered in what he refers to as a “Photoshop tutorial aesthetic” or a “desktop screensaver aesthetic.” His meticulously produced and filmed environments are cobbled together from sources both sampled and hand-modeled. The works are appropriative, both in their subject matter and aesthetic, using elements purchased and then edited for his purposes. They adopt the visual vocabulary of contemporary video games in order to isolate and comment upon digital space as an abstract fact, while simultaneously pushing up against the increasingly tenuous separation between perceptions of the digital and the real.

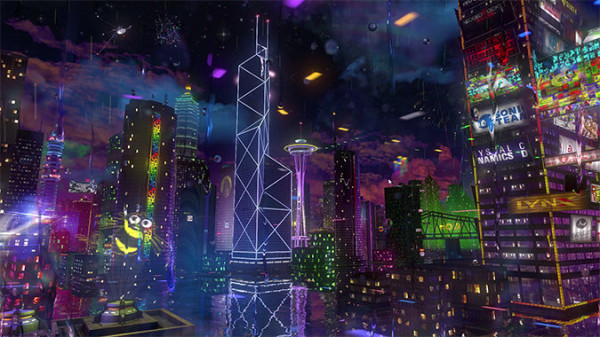

A single-channel piece titled 20XX explores an invented cityscape, made up of the artist’s favorite existing skyscrapers. The video acts as a tour of Robak’s city, consisting of ten-second still shots followed by pans to new locations. The glowing nighttime atmosphere, replete with neon lights and flickering, changing advertisements for real corporations, harkens to science fiction and cyberpunk. The title nods to a convention in videogames and anime, in which dates in the far future are listed as 20XX. The piece is a bittersweet ode to open world-video games, playing on their seductively immersive qualities, but aware of their isolation from the “real world” and human interaction.

Another work consists of two videos of roller coasters, each on its own screen, one traveling through interior spaces and the other through exterior spaces. The environments are taken from sourced panoramic photographs, which the artist has edited extensively in order to make them appear three-dimensional, as well as to remove all instances of human life. With the people gone from the interiors, the work takes on a voyeuristic quality, traveling through lifeless rooms that seem by all measure to belong to others. There is tension between the two channels: the public and the private, both devoid of humanity, strive for the viewer’s attention.

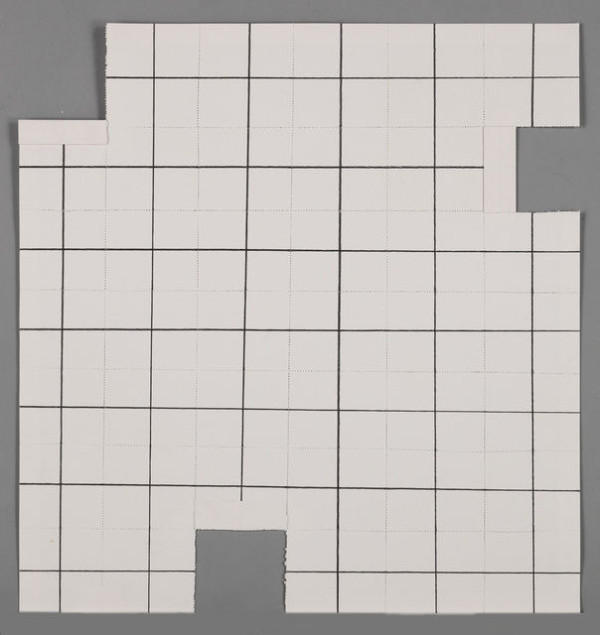

Robak has also programmed and designed a self-playing “match-three” video game, similar to such popular products as Bejeweled and Candy Crush Saga, in which the player tries to align three or more similar items on a grid in order to make them “break” and disappear. The artist used a purchased package of two hundred thousand commercial icons, which he trimmed down to seven thousand, for his source images. The process of production is deeply transformative — the artist has sampled his visuals as well as written a great deal of code to produce this program. Every fifteen breaks, the grid takes on a new, random pattern; the same combinations never appear twice. Displayed on four stacked screens, the computerized gameplay produces a mesmerizing pattern of movement and images.

Xenix simultaneously shows the modeling of four different weapons. The artist is interested in the connoisseurship of firearms, as well as their presentation in popular media, particularly video games. While the weapon in one corner appears dreamy, sleek with psychedelic colors and little implied violence, another takes the form of a sinister pipe bomb built of household materials. A sniper-rifle looks similar to the guns appearing in such mass-market video games as Call of Duty and Battlefield, and is neutered by this familiarity – the weapon’s immediate association is with gaming, rather than actual violence.”