Thomas Demand

Sunday, 20 September 2009

Work from his oeuvre. Also check out his work for After the Imperial Presidency.

“A dozen years ago, Thomas Demand, whose generally stellar midcareer retrospective opens today at the Museum of Modern Art, was studying in London, at Goldsmiths College, then the hotbed of the British art scene. He hit upon the idea to make life-size reconstructions of scenes, often ones he came across in photographs.

The reconstructions were meant to be close to, but never perfectly, realistic so that the gap between truth and fiction would always subtly show. Mr. Demand’s strategy was to photograph his reconstructions, producing the glossy, cinematic color prints also used by photographers like Thomas Struth and Andreas Gursky. Fellow Germans, they, like him but a little earlier, had trained at the art academy in Düsseldorf, although he studied sculpture, not photography. Their photographs had paintinglike presence, which Mr. Demand was after.

But unlike them, he was not photographing real places and, as in Mr. Gursky’s case, then occasionally fiddling with the images. Nor, for that matter, was he imitating Gerhard Richter, who inspired so many artists of Mr. Demand’s generation, by making paintings that suggested blurry photographs. Mr. Demand insisted on being a straight photographer, albeit of sly re-creations – or really, he was a sculptor, making models of places, to produce something that had the quality of painting.

Except that his medium was photography.

Still with me? If so, you should appreciate the cunning of Mr. Demand’s deadpan but lush panoramas, which at their best are hypnotic.

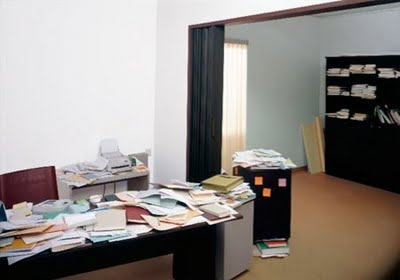

At a studio in Berlin, working just with colored cardboard and paper, Mr. Demand built the stairwell of a school, a hotel bathroom, a kitchen in the hut where Saddam Hussein hid out, a stadium with a swimming pool and a platform diving board, the inside of a neighbor’s house, a television studio, an airport security checkpoint, a copy shop, a thicket of trees – nearly all full-scale models of places, more or less mimicking what he saw in newspapers or magazines but sometimes based on private memories, and always unpeopled, stripped of affect, and strangely pregnant.

Mr. Demand’s pictures owed something to the wry, prosaic snapshots of banal and vernacular places by Ed Ruscha. Except they were devoid of detail and weightless. The photographs provoked a double-take after the inevitable first assumption that the scenes might be real. Then, on closer inspection, other issues revealed themselves.

Those issues included more than just photography’s inherent unreliability, its slipperiness as truth. Mr. Demand’s works are drily vexatious, like Chinese boxes. A patch of grass that he photographed turns out to be a laborious paper reproduction of a patch of grass, made blade by blade, which brings to mind a photograph by Mr. Gursky of a gray patch of carpet, itself devised as an ironic riff on Gerhard Richter’s all-gray paintings, which harked yet further back to Jackson Pollock’s drips. You can recognize this string of connections or not, but either way, the picture retains its flat-footed eloquence, with its unnatural swath of bright green nature, painstakingly made, implying, if not something obvious, then something.

Mr. Demand’s show, 26 works, some of them seen before in New York, and handsomely organized by the Modern’s curator, Roxana Marcoci, begins with “Drafting Room.” Tape, paper and T-squares rest on three long tables, neatly lined up in a white room. It is an architect’s spare studio, with windows to one side, opened to let in air and light. The room, silent, is constructed of a grid of slender pillars, which intersect in the photograph with the row of tables to make an allover geometry out of the picture – a clean, basically white-on-white, modernist image. Color is confined to a rectangle of pale blue paper tacked to one wall and to tiny touches like a red dispenser of Scotch tape on the farthest table.

“Drafting Room” is inspired by a photograph of the studio of Richard Vorhölzer, the architect who was in charge of much urban planning for postwar Germany. Mr. Demand’s photograph reconstructs as a model in his own studio a studio where models were made for the reconstruction of Germany.

The grid of the photograph and the design of the room evoke the Bauhaus aesthetic to which Vorhölzer subscribed, revived by progressive planners like him after the Nazis had vilified the Bauhaus. The cliché of light through the windows implies the optimism of the Bauhaus, rooted as it was in a kind of ethical, pragmatic utopianism. But the light, and so by implication the optimism, is an illusion, like everything in Mr. Demand’s work.

It turns out that Vorhölzer designed the post office in Schäftlarn, a town near Munich, where Mr. Demand grew up. “One’s experience of public architecture develops partly because of such seemingly insignificant places as post offices,” Mr. Demand has said. “For me, as a child, observing that place was highly instructive.” His “Staircase” recreates, as he remembered it (incorrectly, he later discovered), the stairwell of his secondary school. The school was another example of postwar reconstruction architecture. Mr. Demand’s memory having been corrupted by other information, his stairwell in fact most immediately summons up Oskar Schlemmer’s “Bauhaus Stairway,” the 1932 painting in the Modern, minus the people.

Reconstruction and memory. Born in 1964 into the West German boom, Mr. Demand is old enough to remember the 1972 Munich Olympics, when Israeli athletes were murdered, and the terrorism of the Baader-Meinhof group, culminating in its botched airplane hijacking and the deaths (coroners called them suicides) of jailed gang members in 1977. Mr. Demand also knows Mr. Richter’s famous Baader-Meinhof series of paintings, based on forensic photographs and magazine illustrations: images intentionally aloof and, like the truth, sometimes hard to make out.

Mr. Richter painted his series in 1988, as it happens a year after a German politician, Uwe Barschel, was found dead in a hotel bathroom in Geneva. A magazine photograph of his body in the tub, akin to the news shots of the dead Baader-Meinhof members, raised public doubts about the verdict of suicide. In the show, Mr. Demand’s “Bathroom,” adapted from that photograph, suggests a tawdry version of Jacques-Louis David’s Marat, hard light falling on the blue tiles of the tub, the murky water and bath mat.

Mr. Demand has also reconstructed, from photographs, the blown-up room where plotters failed to kill Hitler; the New York hotel room where L. Ron Hubbard spent two years writing; and the studio of an artist whom Baader-Meinhof members assaulted in order to blow up the house of a prosecutor who lived next door. Many of Mr. Demand’s pictures, not coincidentally, entail studios – places where artists or architects or engineers or actors build models or simulate actions. “Studio” derives from a photograph of the 1970’s television set for the German “What’s My Line?” – a program about truth and fiction. “Barn” adapts one of Hans Namuth’s photographs of Pollock’s Long Island studio, emptied and dark, light shining through windows and between the wooden slats, making an allover, mysterious pattern of white on black.

“Studio” and “Barn” are stunning. Mr. Demand is best when his work proffers a kind of strict, modernist opulence amid the sense of loss. That’s the case with the garish color bars of the vacant television studio, a kind of readymade Ellsworth Kelly, set off, rhythmically, against the four chairs and three panels on the legs of the table. And with the red banister, a near-horizontal jolt underlining the cool geometry of “Staircase.” And with the louvered shades in “Window.”

And also with the gray and yellow Post-it notes, diminishing into depth, in “Poll,” which Mr. Demand based on a photograph of a Florida election recount station. The receding tables, like interlocking arcs specked with color, mimic Bauhaus design.

W. G. Sebald, the great and gloomy German writer of postwar memory, once claimed that his favorite haunt in England was the Sailors’ Reading Room in Southwold, because it is “almost always deserted but for one or two of the surviving fishermen and seafarers sitting in silence in the armchairs, whiling the hours away.” Sebald knew the eloquence of empty places. There is also a reconstruction by Mr. Demand of Leni Riefenstahl’s film archive: an empty room with shelves supporting identical gray boxes, hinting at Riefenstahl’s regimental pageants glorifying the Nazis, simultaneously alluding to Donald Judd and Andy Warhol, suggesting that in this clash of cultural aesthetics may be the condition of modern history.

I mentioned London at the start because it was where Mr. Demand, after his training in Düsseldorf, said he had found an appreciation for spectacle for its own sake. “Clearing” is his version of a forest, made up of 270,000 individually cut leaves of green paper, cinematically lighted, based on a spot in the Public Gardens in Venice. Sublime landscape, a German Romantic tradition, is shown to be just another illusion.

But the photograph is uplifting anyway. It’s a laborious sculpture and also a labor of love. Mr. Demand evidently couldn’t help his own attraction to the subject, which transcends its artifice. In the end, the art suggests, even the elusiveness of reality can have its visceral pull.” – Michael Kimmelman for the New York Times