Glenn Ligon

Friday, 9 October 2009

Work from his oeuvre.

Ligon has an opening at the Illingworth Kerr Gallery tonight.

“It’s late on the morning of the US presidential election, and Glenn Ligon is talking about Jasper Johns. “His notion that you take an object – or in my case a text – and do something to it and do something else to it: that’s always been the touchstone for the way I’ve thought about my work.” The displacements and iterations Ligon effects, from returning to source material a decade after first use to hiring an appraiser to perform a condition report on an earlier painting, well attest to this legacy. Yet anyone who has stood before one of Ligon’s text paintings and seen its thick encrustation of oil stick, a product of the artist repeatedly running the medium through stencils, will be hard-pressed to not also think of his forebear’s paint handling. Nor was this connection lost upon New York Times critic Michael Kimmelman, whose review of the 1991 Whitney Biennial identified Johns as ‘the unlikely source’ of Ligon’s paintings. As Darby English previously commented, ‘unlikely’ is the operative word: Ligon, while gay, is also African American, and in an early 1990s moment of what the artist calls “high multiculturalism”, any but the most explicitly identity-based work failed to compute.

“There was an assumption that artists of colour could only and would only talk about their identity”, he recalls. “From the beginning, myself and a whole group of artists – including Lorna Simpson, Gary Simmons, Fred Wilson and Kara Walker – resisted the notion that there was some easily identifiable, unified, readily agreed-upon thing called blackness that we could present in our work.”

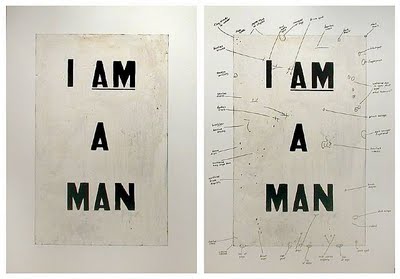

Ligon’s engagement with literary and vernacular quotations, beginning with a painting excerpting a sign wielded by demonstrators at a 1968 black sanitation workers’ strike (Untitled (I Am a Man), 1988), reveals a far subtler understanding of the personal and sociocultural delineations of the self. As a statement, ‘I am / a man’ captures the complexities of political action, in that its assertion of a seemingly evident fact calls attention to the very condition of social invisibility that necessitated it, while its circulation through collective action risks inscribing a group of individuals with still another set of norms. By transposing this message from the placards of protestors to the surface of a canvas, and dividing up the quote (‘I am / a / man’), Ligon widens the discursive rift, and we are left to consider the subject for whom this phrase has hauntingly returned.

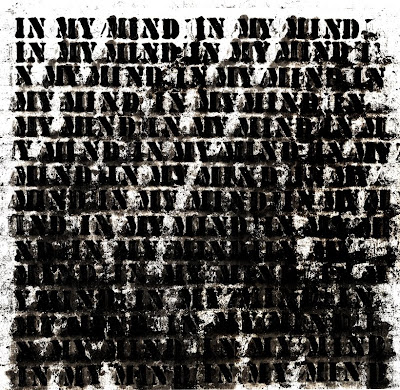

Subsequent text paintings, many originating from etchings, introduced Ligon’s now characteristic use of oil stick and text stencil, with seminal lines from Zora Neale Hurston, Ralph Ellison and other authors repeating over page- and scroll-proportioned surfaces, progressively muddied by the accumulating paint. “The way I use quotations is almost like adapting a novel for a film”, Ligon remarks. “It’s based in the text, but it’s not the same thing. It has its own structures and desires.” The thick, material life Ligon gives his quotes can be taken as symptomatic of “the text’s unconscious”: a latent realm of wish and fantasy that manifests at the limits of legibility.

Hurston’s 1928 statement ‘I feel most colored when I am thrown against a sharp white background’ receives analogous visual form in many of Ligon’s renditions, the black paint settling with increasing randomness upon a white surface that appears as its seeming and ever-eclipsing precondition. As with the artist’s other bodies of work, the ready significance of the colour palette is less a conceptual endgame than one pole of an axis traced between absent body and absent voice.

Hurston’s address retains its specificity and resonance several decades hence, while its compulsive multiplication draws out the community it synecdochically serves. ‘Much of Glenn’s investigation has been about how the “we” replaces the “I” when the black subject is being considered’, curator Thelma Golden has observed. In other words, while using the first-person voice, his quotations ‘speak for an entire experience’.

If this repetition of source texts overstates, so as to highlight a community’s historical lack of representation, it also points to Ligon’s tenuous status as a member and as the artist doing the quoting. His decision to speak through borrowed words is bolstered by the indirect, stencil-based handling of his medium, such that the resulting paintings’ very evidence of making is the residue generated by his execution of a predetermined script. Any definitively authorial trace is thus substituted with a presentation of alienated labour to accompany those of the other partial and qualified selves on display.

Ligon also problematises his role in other bodies of work, adopting particular modes of biographical narration in a fashion that reveals more about their relative conventions of storytelling than their alleged subject. Two-channel video The Orange and Blue Feelings (2003) finds the artist engaged in a session with his therapist, the cameras notably angled away from the talking heads and respectively towards the office bookshelf and the therapist’s legs, and the conversation generally affirming the well-known truth that the ‘talking cure’ is a performance like any other, with a 45- minute running time and an office for a set. A series of etchings entitled Narratives (1993) masquerade, in format and style, as the opening pages of nineteenth-century slave narratives, often replete with an amendment, by a fictional white abolitionist, authenticating the authorship of the tale to follow. The accounts detailed on these pages are pointedly biographical, including one about Ligon’s early education in a predominantly white New York school and another summarising his life as a homosexual. During the same year, Ligon invited friends to write short descriptions of his appearance, which became the content of a series of lithographs modelled after runaway-slave notices (Runaways, 1993). The implication is that these formats continue to inform the construction of the minority subject in both personal and public consciousness, a point Ligon emphatically makes in one print from Narratives by connecting the double-edged consumption of slave narratives with that of contemporary black art (‘Glenn Ligon / … / His commodification of the horrors of black life / Into art objects for the public’s enjoyment’) and in Runaways by asking friends to write their descriptions as if they were describing a suspect for a police report.

As much as these different working methods have helped Ligon avoid the ‘minority artist’ moniker, they have also allowed him to sidestep the institutional trappings that commonly befall midcareer artists. Ligon could not properly be said to work in series or periods: he visits and revisits quotations and bodies of work, at times producing more than a dozen print and painting variations on a single source quote and even crossing media to append his ideas. The process affords the artist a twinned perspective on his own output: as the author of work that by its very nature challenges assumptions of authorship; and as an interpreter who sources bits of his own practice as he would any other good in the cultural domain. This may explain the hesitation of the curators of Glenn Ligon: Some Changes, the recent touring survey of the past 17 years of his output, to characterise the show as a retrospective. “Calling it a retrospective would imply fixed bodies of work that can now be studied”, Ligon reflects. “My show was deliberately titled Some Changes with the idea that the work was always work-in-progress and could take other forms in the future.”

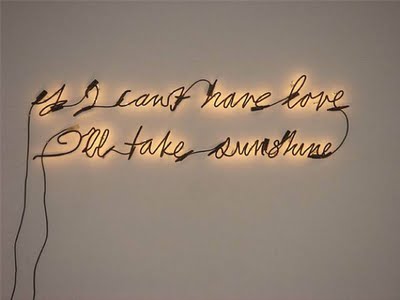

Among the products of Ligon’s cyclical process, A Feast of Scraps (1994–8), a vintage scrapbook interwoven with assorted homosexual imagery, was revisited in 2003 as the aptly titled Annotations, a digital variation that allows users to click on photos and uncover chains of associated images and songs, some disclosing the flipside of the scrapbook’s buttoned-up veneer. Ligon has also borrowed the phrase ‘negro sunshine’ from Gertrude Stein’s 1909 novella Melanctha for a series of drawings that he later turned into his first neon piece, Warm Broad Glow (2005). The black paint customarily applied to the back of neon instead covers its front, diverting the light into an intense halo that emanates from behind, and elegantly touching on the issues of opacity, repression and invisibility that occupy his practice as a whole. Even then, Ligon produced other versions of Warm Broad Glow, including one for his 2007 exhibition at Regen Projects, in Los Angeles, which was painted entirely black. “If phrases are resonant enough”, he observes, “they cannot be exhausted. Other meanings can be teased out of them, partly by a change in medium or approach.”

In recent years, Ligon has returned to a group of paintings made a decade earlier, which featured jokes from Richard Pryor routines. “I wasn’t done with Pryor or he wasn’t done with me”, he says with a laugh. “If you go back and listen to his albums, they are very pointed critiques of American society. They are from the 70s, but he was quite prescient.” While a series begun in 2004 traded Ligon’s earlier monochromes for a palette he playfully calls “off-colour”, his 2007 Regen Projects exhibition comprised 33 renditions of the same joke, in black, on square gold canvases. The paintings encircle the gallery like a thin gold band, punctuated by differences in paint application as well as by three equally sized paintings with other Pryor jokes. If these works position the audience at the threshold of reading and viewing, then the installation in turn builds an affective syntax, letting us scan the paintings as we would a line of text in an environment that also necessitates bodily engagement.

“It was important to me to return text to the speaking voice”, Ligon comments. “Jokes seem to require that you say them out loud, which is different than a text from an essay. I noticed that people in that show performed the work, performed it for each other, told each other the jokes. There was something in how that installation worked that brought up memories of Pryor’s physicality and forced a performative relationship with the text.” – Tyler Coburn for Art Review