Jennifer Steinkamp

Monday, 15 November 2010

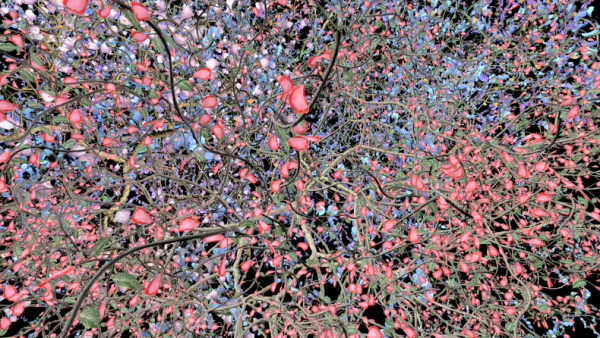

Stills from

Daisy Chain video installation

The Wreck of the Dumaru video installation

and Orbit, 2 video installation

“My artwork uses computer animation to craft immersive interactive projection installations. Three dimensional computer graphics are the basis of my animation; animations that take full advantage of the computer’s ability to create motion and points of view that are not available by any other means. Projectors are strategically placed in a space, and the projections of the animation are then fitted or remapped into architectural situations; the art can then be experienced physically in relationship to one’s movements through the space.

The first installation I executed was a multiple site work titled Gender Specific (1989), a piece created for my undergraduate thesis at Art Center College of Design. It began as an installation for a house in Pasadena that was an artist run alternative gallery space called Bliss; subsequently it was also exhibited in a storefront at the Santa Monica Museum of Art, California. Both pieces ran simultaneously in different parts of the city and viewers would have to drive across town to experience the entire installation. Issues surrounding the cultural specificity of gender in relation to domestic and consumer architecture were addressed by bifurcating the architecture and sites across town.

I use light to dematerialize space.

As my ideas and the work developed, I found I could dematerialize architecture by combining light, space and movement. I had always been fascinated with the light and space artists such as James Turrel; his perceptual light illusions transform our experience of architecture. Following this tradition, I investigated how light could create an illusionistic sense of space and dimension. Unlike the light space artists, I added the component of motion to my light projected illusions that made the architecture appear to dematerialize. I first came across this visual phenomenon when I created Untitled (1993), a floor projection piece. A colorful water animation was projected from the ceiling down across the floor. The inanimate floor seemed to breathe; the architecture was transformed by light. The viewers perceived the non-physical components of the imagery and light corporeally. People actually experienced the physical sensation of seasickness. Ever since creating Untitled, I set out to investigate illusions that transform the viewer’s perception of actual space in a synthesis of the real and virtual

Shifts and Decentering

I have used various methods to decenter or reconsider subjectivity; another installation titled, The TV Room, for the Santa Monica Museum of Art: the image formed a disorienting parallactic shift as the viewer moved through the room. Three wall strips stretched horizontally across a room in the museum; animated water streams were projected on each strip. The wall behind was filled with a multi-colored waterfall. The back surface and the wall strips interlaced to form the image, somewhat akin to the scan lines on a television set. Further shifting occurred as the animated imagery tilted, consequently, the architecture, virtually destabilized, it felt as if it were tilting as well. The viewer, unable to decipher the half wall, found the experience disorienting.

Shadows

With many of the installations, the viewer’s shadow becomes part of the image as she passes through the projection, partially disrupting the image, breaking the illusion. The projectors are often placed low so the viewer has no choice but to become part of the work. Children immediately understand that they are expected to play in the projection. Humor and play are important aspects of the art; these are further ways of involving the viewer as part of the work. As the viewer internalizes the image in her mind, she also experiences it physically and narcissistically (though their shadow) in real space.

Some of the imagery I use tends to be more abstract, I am intrigued with abstraction because the point of view in abstraction is complex and perhaps not fixed. You could ask, where is the point of view in abstraction? What is the viewer’s relationship to an abstract image? This thought has had a profound effect on my contemplation of abstraction and subjectivity.

My work has evolved out of a deep interest in issues of feminism. My site-specific installations set up complex relationships between the viewer and the viewed. With the environments I create, the relationship between viewing subject and art object is recast. My work engages with the spatial politics of vision. It breaks down standard — often male coded — modes of seeing to create a more open physical state of pleasure that includes all genders. My work is influenced by the pioneering feminist film theory of the seventies, especially Laura Mulvey. I am interested in investigating ideas such as the patriarchal gaze, point of view and objectification. With the help of virtual technology, my work sets out to de-center and reconstitute the viewing subject as we know it.

Collaboration

I have collaborated with three composers over the years. Their music is a very important part of the work: music creates the atmosphere, adds mood and emphasis to certain visual elements. The soundtrack creates a sonic dimension to the space; the physical space is transformed by the audio. For example, the interactive piece titled Phase=Time, exhibited at the Henry Art Gallery, Seattle: composer Jimmy Johnson and I placed 8 speakers around the perimeter of a large square room, the sound traveling across each speaker transformed the square gallery into the sensation of a circular space.

To date, I have collaborated on twenty-three pieces with Jimmy Johnson who had an electronic music group called Grain. I have also collaborated with Bryan Brown whose band is called Blue Bird, additionally, he is the drummer for surf guitarist Dick Dale; I have also collaborated with an experimental composer and artist named Andrew Bucksbarg. When collaborating, I come up with the structure, or space for the piece. I usually create a virtual scale model on the computer, and then discuss the ideas behind the work with the composer. We get together a few times testing the sound in relation to the space and image.

My first collaboration with Jimmy Johnson was part of an exhibition and symposium on photography. You might say our work was a far extreme of photography, especially since I never use imagery from the real world; everything is synthesized in the computer. On the other hand, Jimmy used highly manipulated sound samples of Helen Keller speaking to an audience, by the time he was finished the sound sample was unrecognizable. I conceptually linked the work for this exhibition to photography by utilizing three intersecting landscape topologies that moved in and out of focus on a grid. A “photographic” aerial view of my constructed landscape was remapped into the space.

Technology

As I mentioned, the imagery, synthesized is derived from software tools, not the world. I use Alias Maya Software, a 3D animation package used by the film industry for special effects; Adobe After Effects for compositing; and Macromedia Director for interactivity. As new virtual reality software tools develop, my work effectively changes; in a sense the software developers are collaborators. I often use particle dynamics and paint effects, a set software tools created to simulate natural phenomena. These are interesting because they are unpredictable; you can assign the particles a life span, tell them what color to be over their life, and attribute how they will respond to environmental variables such as gravity, turbulence and wind. You dial in these variables, and then run the simulation for a few hours. It can be a pretty random process and it can take a couple months to complete an animation. Because particles were created to simulate physics, they synthesize a very realistic quality of motion. I have long since been interested in “life-like” motion. This is always the challenge for an animator or anyone who thinks about movement.

Over the past couple years, my collaborator, Jimmy Johnson and I have been adding the component of interactivity with sensors. We completed a large-scale piece titled Stiffs (2000). I knew almost immediately that I wanted to create large floor to ceiling monoliths, the forms would fill the space while referencing some of the existing proportions of the gallery. I imagined the monoliths as a forest of tall figures or trees. We further emphasized this by arcing the animation and sound around the viewer as they approached each monolith; the image would envelop the body. The viewer has always been an integral part of the artwork – their shadow disrupts the image, breaking the illusion of the projection. Their playfulness and movement though the space creates the experience. With Stiffs we explored spatial interactivity, using ultrasonic sensors to track the viewers relationship to each monolith. As the viewer approached the monolith, the animation would speed up. Another couple of sensors at the far ends of the gallery sent the image and sound into a chorus; all the monoliths sang together in unison. It is an interesting challenge to construct interactivity in a large space for many viewers without loosing the impact or experience of the work of art.

Genres and Influences

The question is often raised about what genre these art works can be said to inhabit. They obviously can be considered part of the new media art genre because of their origins in, and reliance upon, computer based technology. At the same time they are part of a long evolution in installation art. These are the two most overarching genres; but there are many other ways to categorize this work; and it has been included in many types of exhibitions, including: feminist, video, digital, interactive, photo, and abstract painting.

3D computer graphics, virtual reality if you will, is a new medium for artists. I find it extremely gratifying to work with these adept tools. Works of art can be created that have never been experienced before, although this can also be all too tempting. I feel a great responsibility to create artwork that engenders poetic resonance. Artwork should perform on many levels; it can be accessible and interesting to an untrained audience, as well the cultural vanguard. One of my greatest challenges is to create a work where complex ideas can be best experienced as works of art.”