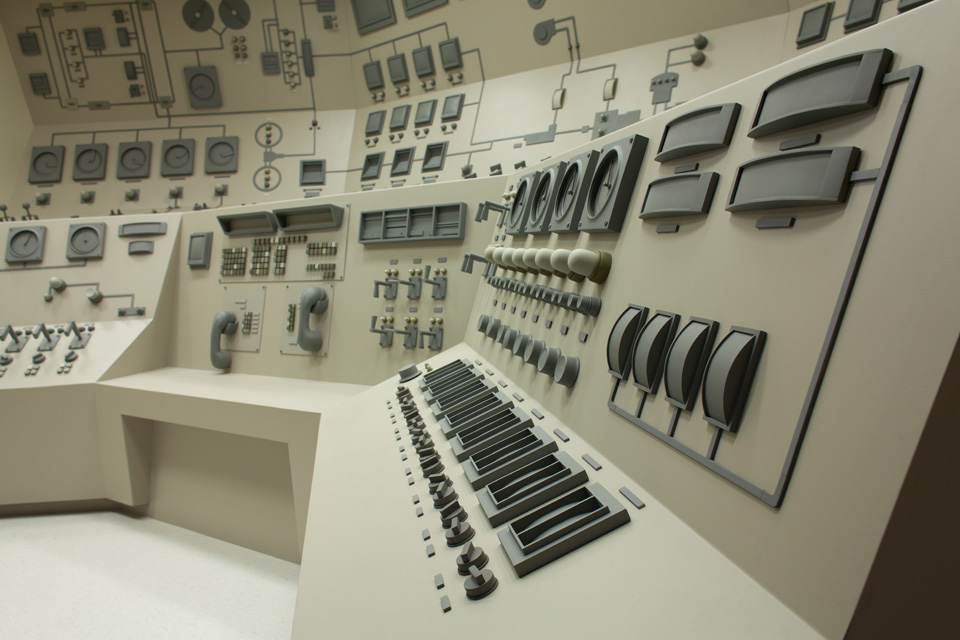

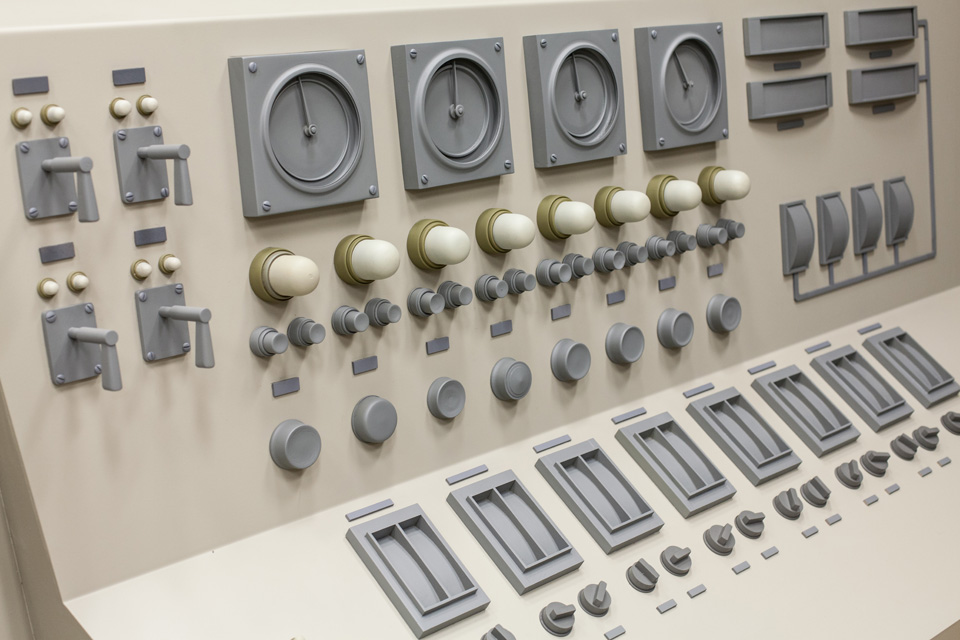

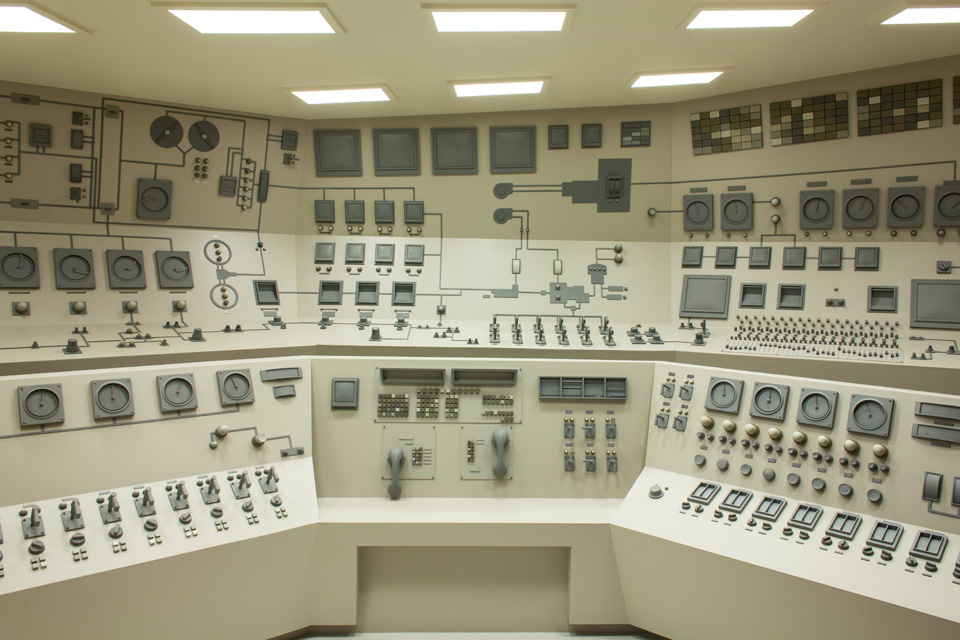

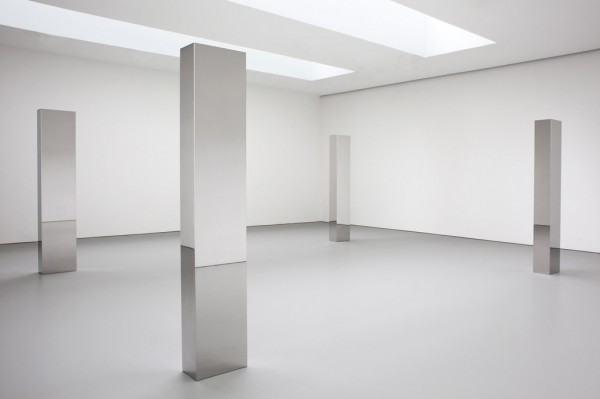

Work from Apparatus at Kavi Gupta.

“Roxy Paine’s work has challenged the perception of visual language and how it affects the understanding of our environments since the genesis of his career in the early nineties. Focusing on objects and their fabrication, Paine strives to evoke a desire to understand how meaning can transcend through time, using our conventional relationships with the visual as an anchor for the exploration of truth. Paine’s contemplative work has ventured into two distinct, yet related, avenues of artistic production. Highly acclaimed for his synthetic replicas of organic forms such as fungi and trees, intricately executed with impressive mastery and ingenuity, and his computer-driven machines programed to auto-produce works of art, Paine presents a complex arena where the balance between what we know to be true and what we can learn from a deeper contemplative observation is considered. A truth dependent on our willingness to accept the beauty in the imperfections within nature and language itself, a balance in paradoxical poetics.

With Apparatus, Roxy Paine introduces a new chapter in his work, a series of large scale dioramas. Inspired by spaces and environments designed to be activated via human interaction, a fast-food restaurant and a control room, the dioramas present spaces and objects which are hand carved from birch and maple wood and formed from steel, encased and frozen in time, void of human presence, making their inherent function obsolete. Rooted in the Greek language, diorama translates to “through that which is seen”, a definition that has evolved throughout time as dioramas became conventionally known as physical windowed and encased rooms used as educational tools. Paine transforms the environments on display by using the diorama’s traditional experience as a tool to create a contemplative experience where what we see behind the glass transitions between being real and being a mere shell of something real. These dioramas are not intended to be specific or accurate replicas, but merely gestures of their real life inspirations. As Paine himself states; “they are translations from one visual language to another”. The environments ask the viewer’s to consider their pre-conceived knowledge of the mechanics and functions of a fast food restaurant and that of a control room, as well as open up to the possibility of how this knowledge can, and will, change through time and context.

Japanese culture has a term known as Wabi-Sabi, the idea of art and architecture addressing how the natural change and uniqueness of objects helps us connect to the world and how we can transcend significance and meaning with inevitable change and time. Paine has constantly innovated ways that address impervious knowledge and challenged it with almost impossible transformations, taking into consideration the concepts behind Wabi-Sabi to find a balance in the inevitable changing nature of the world. Though human language relies heavily on social convention and learning, Paine strives to push the boundaries of that process. Paine’s dioramas, along with his previous bodies of work, serve as reminders of the knowledge and enlightenment that comes from actual, real, experience with our natural and fabricated worlds.” – Emanuel Aguilar

Photo Credit: Joseph Rynkiewicz, courtesy of Kavi Gupta CHICAGO | BERLIN