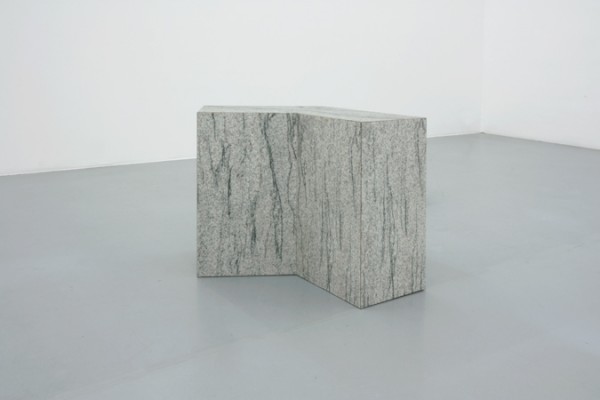

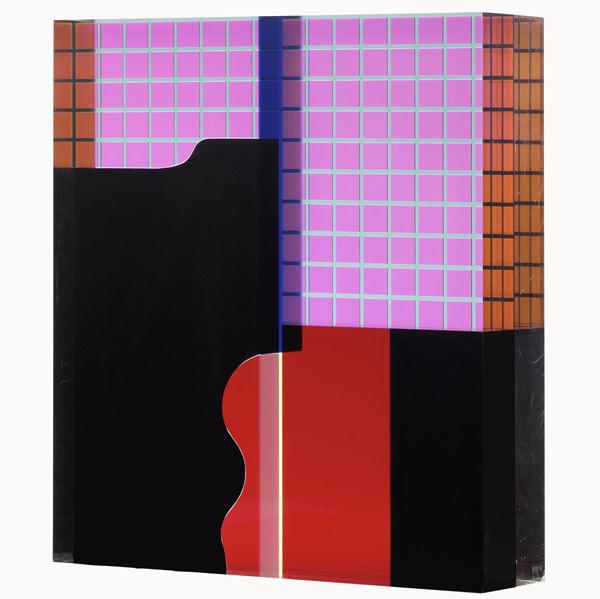

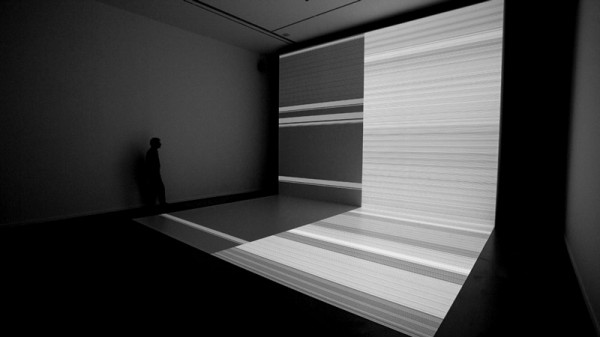

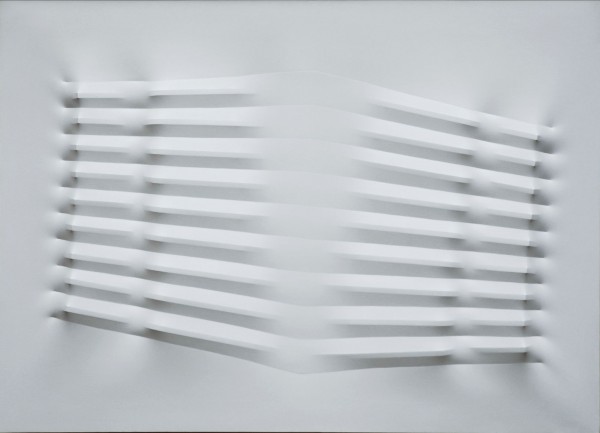

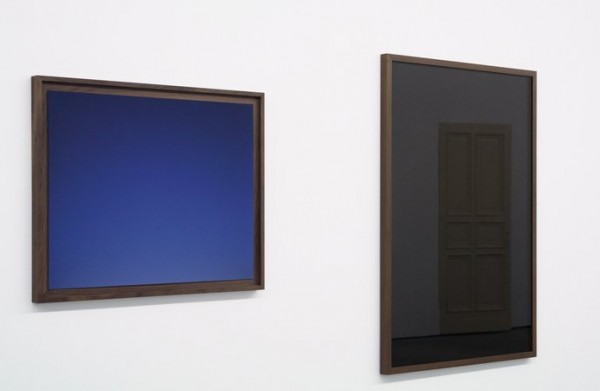

Mandla Reuter

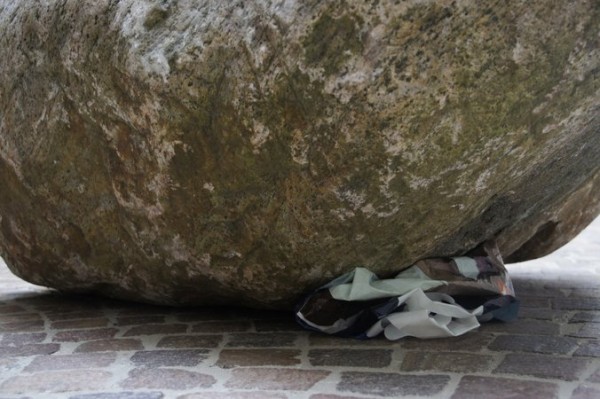

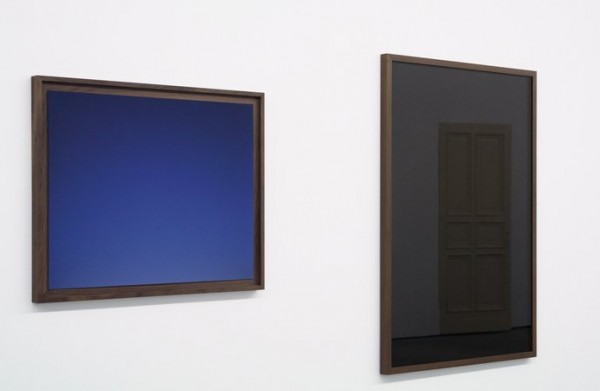

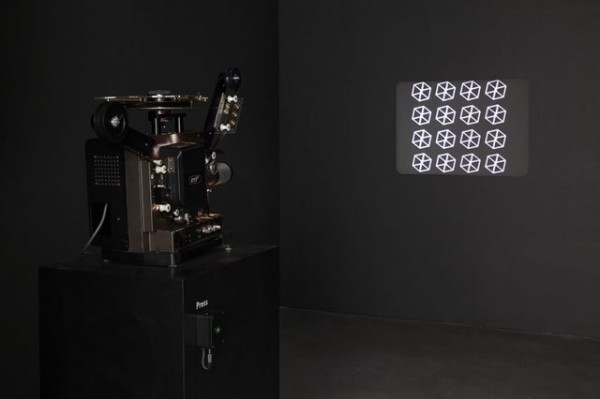

Work from his/her oeuvre.

This artist was found (as many have been in the past) on VVORK, Reuter’s image marks their last post of regular daily activity. If you haven’t spent time with their archives, I highly suggest you do so – it remains one of the most relevant and rich resources I have come across.

“KR: When taking a look at catalogue and press texts written on your exhibitions, your artistic approach is preferably described as one that by means of – in part explicit, in part minimal – interventions sensitizes one to specific institutional states and sheds light on the architectural, aesthetic and social conditions of art production and reception. In this context, my first question addresses concrete strategies, or rather, your specific methodology of producing shifts. What happens when rooms, architectural elements, doors, entrances etc. are ‘doubled’, for example? How does it function, how does it operate? What interests you most when doing this?

MR: These frequently mentioned shifts in my works are produced in a variety of ways; it is most often the case that an object in the room or an architectural alteration serves to create certain situations, which then form the actual core of the work. As far as I know, doubling, except for a few examples, doesn’t necessarily play a prominent role in my work, yet regarded as a very fundamental and old artistic means, it is of course interesting.

In the exhibition Isolated Human Particles Floating Weightlessly Through the Magnetic Stream of Fabricated Pleasure Occasionally Colliding (2006), doubling was naturally a pivotal moment. Two identical exhibitions were juxtaposed. They were simultaneously opened at two different locations in Frankfurt, with identical opening addresses and of course identical works. Yet the two shows each had a very different character, because one took place in a private flat and the other in a public exhibition space. The central and largest piece, which was at the same time relatively inconspicuous, was the only one that was not doubled in the classical sense.

The Move (2006) consisted in relocating the entire furniture and possessions of Meike Behm and Peter Lütje, the operators of the exhibition space rraum, to the back room of the public institution. The move was carried out by a removal firm which thus became part of the work. This lent the exhibition in the flat a relatively neutral appearance, while in the other art space the objects were stored. Less as a sculpture than as a mere mass moved within the frame of the show. Among other things, The Move played with the immense effort made in the backstage areas of large concerts, during film shootings and other cultural events. In my case it was a more or less meaningless effort standing for itself within the frame of the two exhibitions.

KR: I would like to add a further question here that has to do with the way your work is received or interpreted. Vanessa Joan Müller describes your works as “context-related installations”, and in the press release of the Berliner Flutgrabenfabrik on the awarding of the GASAG Art Prize 2007, talk is of “situation-specific installations”. What do you think: Do these positive references to the concept of installation as well as avoiding the use of the labels site-specificity and institutional critique have to do with trends in art criticism, or to what extent do they necessarily result from your work? You yourself just spoke about creating certain situations…

MR: It could perhaps have to do with the difficulty, but also the alleged necessity, of attaching a label to an artwork or trying to explain it, to make it comprehensible and place it in a context using familiar concepts. The terms used here, “context-related installation” and “situation-specific installation”, are not necessarily wrong, but they are probably more confusing than that they contribute to elucidating a working method. I would rarely describe my work as situation-specific, site-specific or context-related. The works are conceived in such a way that they can function independently of the site, and usually independently of the context as well. It is the contexts that change artworks, no matter what they are like. My work is not institution-critical either, at least that’s not how I see it. Perhaps one could have spoken of institutional critique if the works had been produced in the 1970s or 80s, but today such concepts often do not go far enough and tend to pigeonhole artistic works, thus making it almost impossible to read and deal with them in a farther-reaching, sensible way. In most cases I find these currently widespread artistic positions that present their political, ecological or institutional grounds in advance extremely difficult. I don’t want to be misunderstood here; of course it’s fine if an artwork functions as a political statement or can be very political in itself, but not as a priority and as the sole starting point of a work. Maybe that also has to do with trends in art criticism, but certain developments can be found there as well. In general I try to avoid these labels, even if it doesn’t always seem to work, as one can see. When I speak about works that create situations, I mean the circumstances and the possibilities of perception that are produced by an artistic intervention and that lead away from their actual materiality, allowing a number of interpretations. Basically that’s what happens with every picture hanging in a room. And of course I would like my works to be seen foremost as pictures; I’m an artist and artists create pictures. All one can say about the concept of installation is that any picture hanging on a wall becomes an installation, perhaps the respective artists have different priorities, but in the end what largely contributes to the reception of a work is how it hangs in the room and what it does to the room…” – from the inteview with Karin Rebbert.