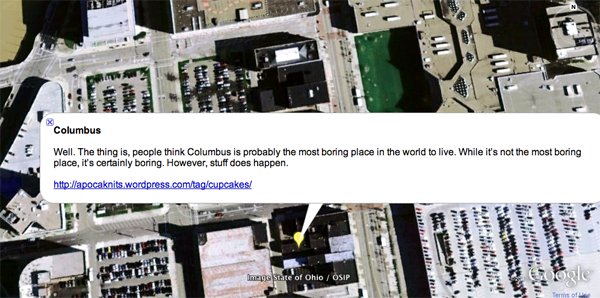

Michael Schmelling

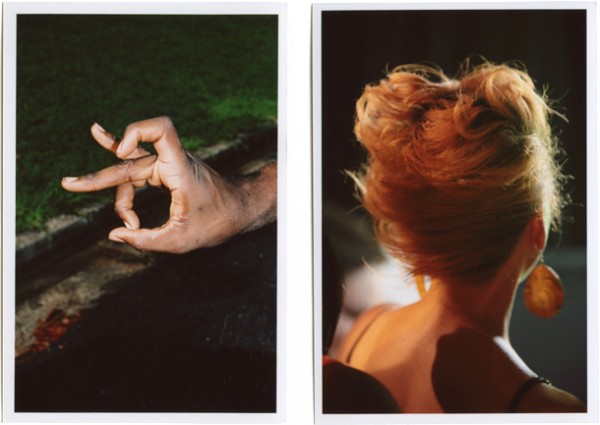

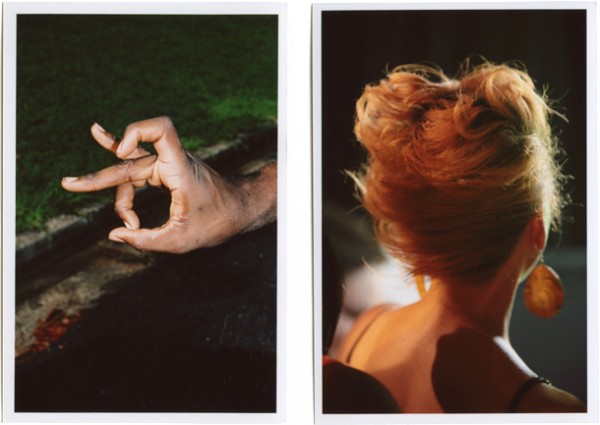

Work from Atlanta Revisited.

“Michael Schmelling’s Atlanta is a photographic tour through that city’s hip-hop scene, arguably the most influential music community of the past decade. And while Atlanta (out November 1 from Chronicle Books) includes interviews with big names such as Outkast’s Big Boi and André 3000, Ludacris and The-Dream, Schmelling focuses on the more protean realities of young musicians aspiring for their next big break. (In true hip-hop fashion, the book even comes with a downloadable mixtape of unreleased songs.)

Schmelling’s photographic style, though highly varied, bears a closer resemblance to the abstracted mundanity of Southern photographic legend William Eggleston than to New York rap documentarians such as Ricky Powell or Martha Cooper. As Schmelling says, that’ s because the Atlanta music community isn’t about glorifying past heroes. The perpetual obsession is on what’s next.

KEN MILLER: Why focus the book on younger performers instead of the big names?

MICHAEL SCHMELLING: Even by the standards of rock and roll, hip-hop belongs to its youth. There’s no shortage of big records by teenagers that have come out of Atlanta—Kriss Kross, Crime Mob, Soulja Boy… Soulja Boy was 16 and just blowing up when I started the project, so that really reinforced this notion that youth plays a huge role in Atlanta music. I guess it’s fair to say that most people have a pretty good idea of what mainstream hip-hop looks like, so I was really interested in seeing what hip-hop looks like just before it gets big—the moment before things happen. We’ re used to seeing a bit of the underground side of rock music and indie rock, but we don’ t get to see as much of it in visual depictions of hip-hop. I ended up gravitating towards people that were making music on their own, mostly out of their homes. Lots of them were just out of high school, making their first mixtapes, demos. There’ s a raw, do-it-yourself immediacy to the music that I really love.

MILLER: What do you think makes Atlanta’s music community so particularly vibrant?

SCHMELLING: Well, part of it is that youthful aspect—and then there’ s also the fact that Atlanta has always functioned as the South’s economic hub. But I think what really keeps the scene so dynamic—and this is something [New Yorker staff writer] Kelefa Sanneh mentions in the book as well—is the fact that Atlanta hip-hop doesn’ t restrict itself to just one sound or one way of making hip-hop. Anything goes. People are open to all sorts of different sounds and trends. It’s like, if it sounds good right now, then it’s good.

MILLER: Tell me a bit about the underage parties you photograph in the black-and-white section of the book…

SCHMELLING: On any given weekend there are a bunch of parties like these being thrown in the Atlanta suburbs. Most of the ones I went to were in Decatur, Stone Mountain, Tucker, Norcross, [which are] far from the city center, but still very much a part of Atlanta. They’ re thrown in semi-defunct bars, old clubs, skate rinks or storage warehouses. They’ re more all-ages than underage—lots of the kids are just out of high school. The rooms are pitch black, occasionally lit with a strobe light, very hot, very loud. Usually it’ s five or 10 bucks to get in.

MILLER: Atlanta is dedicated to Joshua Holder. Can you tell me about him?

SCHMELLING: Joshua Holder—AKA Midnite—was one third of 3rd Degree, one of the groups featured in the book and on the book’ s mixtape. Midnite made all the beats for the group. There’ s a bunch of pictures in the book from his bedroom, which doubled as 3rd Degree’ s studio. He was killed last May in a work-related accident.

MILLER: What’s up with the collages?

SCHMELLING: It was really important to me that the book have more than one way of looking at the scene—more than just one type of photograph.

MILLER: Do you have a favorite interview from the book?

SCHMELLING: I love the Gucci [Mane] interview because it delves into the economics and machinations of the scene. That stuff is so hard to get a handle on—the economics in particular—so it’s cool to hear him explain this idea that it makes more sense to buy a cheap classic car and put $200,000 worth of work into it instead of buying a Ferrari, ’cause the Ferrari would just call too much attention…” – Ken Miller for Interview Magazine.

via Zero1