Work from his oeuvre.

“Appearing from out of the darkness, Lyota Yagi opens a small box and takes out a number of remote controls – those everyday items that one uses to operate household appliances from a distance. When he moves the arm which is holding a remote, while also holding down a button, a stuttering kind of noise comes out of the speakers in front of him. Somehow, the electric signal from the remote is being received by a device and being transformed into speech sounds. Watching this, you notice that the sounds change according to which remote is being used, and that the position of the remote itself affects your sense of distance from the sounds and even the balance between the left and right speaker outputs. Seemingly in response, the lighting turns on and off and a camera flashes like a bolt of lightning. After a while you realise that this is a work which takes what can’t be seen, (the signals sent from the remote controls) and actualises them (through our perception of the sounds from the speakers).

This was one scene from a live performance on April 18 at Snac, a new performing art space in Kiyosumi-shirakawa. A collaboration between contemporary artist Lyota Yagi and musician Shuta Hasunuma (who has had music released on the Weather/Headz label, among others), the performance employed Yagi’s piece ‘Remote Con-Troll’ as a musical instrument. It’s this work which forms the focal point of his current solo exhibition, ‘Jisho sonomono e / Zu den Sachen selbst!’ (‘Towards the event itself’).

Lyota Yagi has the image of being an artist who deals with themes involving time rather than sound. This rap is largely due to his work ‘Vinyl,’ which was exhibited at events like his solo show ‘Emergencies #8 “Kai-ten”’ (NTT InterCommunication Center, 2008) and the group show ‘Winter Garden: The Exploration of the Micropop Imagination in Contemporary Japanese Art’ (Hara Museum of Contemporary Art, 2009). ‘Vinyl’ is a record player that plays records made of ice. As the ice melts, the pleasant sounds turn into noise. Critics tended to focus on its expression of how the passing of time brings about change, rather than the changing of the sound itself. Yagi felt that perhaps he needed to correct this mistaken kind of perception, and his current exhibition actually focuses on making the viewer perceive those things they are not aware of.

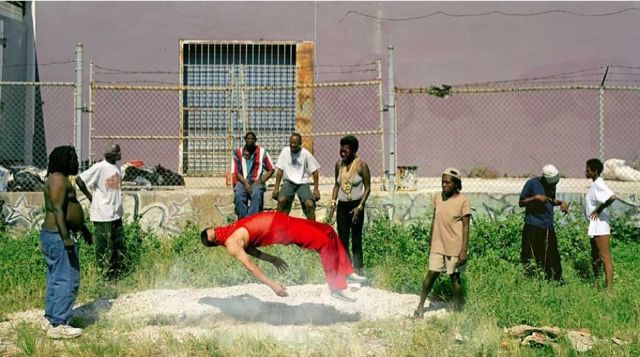

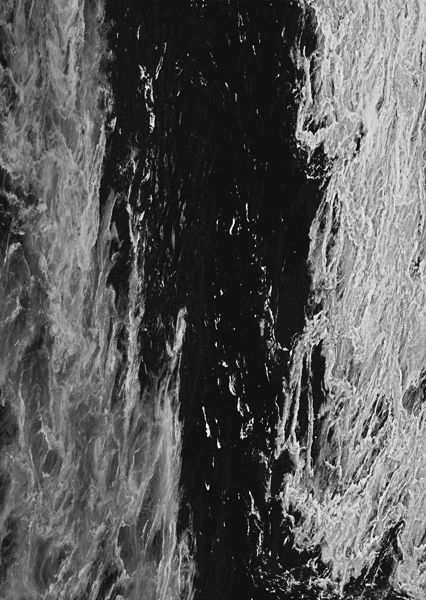

For example, in ‘Remote Con-Troll’, what we are usually unaware of is the signal being emitted by the remote controls. In another of his works, ‘Tsukue no shita no umi’ (‘The ocean underneath the desk’), a waist-high tabletop has been made to look like the surface of the ocean, and there is a pair of headphones for the viewer. If the piece is viewed while standing, the sound of waves can be heard, but if you crouch down, it changes to the sound of being underwater. It brings to mind the world seen from the perspective of a child, an experience that everyone has had in the past but perhaps has forgotten.

‘Yottsu no isu de dekiru koto’ (‘What you can do with four chairs’), is like a game where you have to guess what is written on your back – and takes the idea even further. One person has to imagine what is being drawn on a canvas close to their ear simply by listening to the sound of the pencil moving across the canvas, then that person has to draw that picture on a canvas near the ear of the person next to them – in that way a message keeps on being passed on. It makes us recognise the imaginative power contained in these messages, messages that use a kind of communication which pre-dates language.

Lyota Yagi’s way of thinking, which takes the functions and meanings found in everyday tools and diverts them to completely different uses, is childlike in its simplicity. He uses things so familiar and so ordinary – those things that we don’t usually even notice – and that is what makes his work so surprising, like being suddenly attacked from behind. Before we know it, we are reflecting on our own lives too. Is he a terrorist without a crime, or simply a mischievous child? In any case, his work makes us acknowledge all of the things that we pretend never happened or never existed, because it makes us feel better or more content. Yagi shoots at the blind spots in our consciousness with a deadly accuracy.” – Time Out Tokyo

via VVORK.