Saturday, 12 October 2013

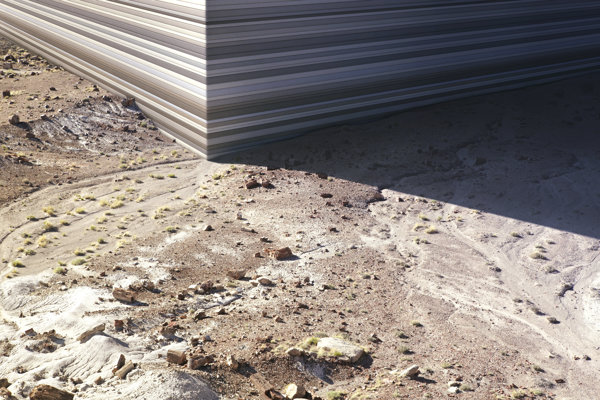

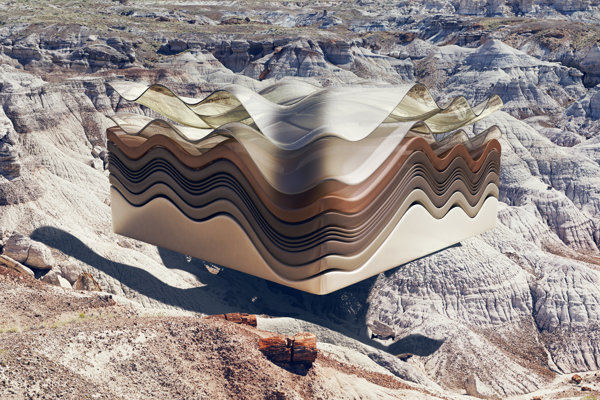

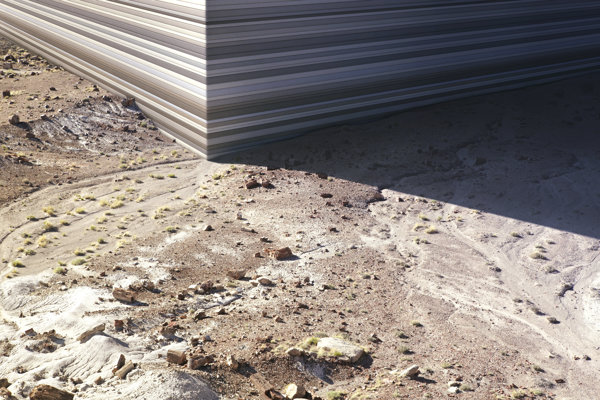

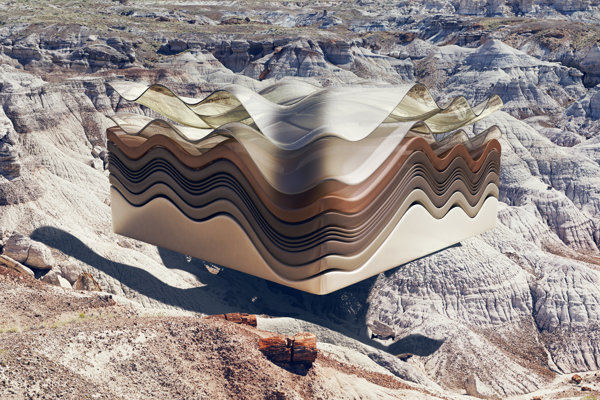

Zeitguised

Work from Badlands.

“Exploring the Arizona desert landscapes, the photographer’s camera becomes the recorder of the original source, while the artist’s digital modeling tool interprets the phenomenology of the geological formations. The resulting world becomes a striking and uncanny walk-in bastardization between the rich reality of the landscape and the reduced analytic model thereof.” – Zeitguised

via Field Notes

Tags: badlands, color, commercial, digital, nature, photography, pixel, weird

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on Zeitguised

Friday, 11 October 2013

Mårten Lange

Work from Another Language

“In Another Language Mårten Lange examines the natural world and the sciences surrounded by it. By capturing flora, animals, and natural phenomena he creates a visual enigmatic and intimate world where the subjects are distanced from their environments; they appear as sculptures in frozen photographic moments.

The aesthetics of science and the materiality of the depicted objects are constantly emphasized and explored in Lange’s black-and-white images, which result in an ambiguous and unreal index of nature. InAnother Language, Lange reiterates photography as documenting and voyeuristic means, while he lingers upon how the visual image can capture shapes, patterns and texture. The world we are entering, the objects we are viewing, and the other language the photographs read, bring us to a secret and mythical world. The idea of ‘other language’ is thus two folded; nature and its laws can be seen as one language, while the idea of photography as a language and system is underlined throughout the project.” –Melk

Tags: another language, black and white, natural phenomena, photography as a language, swedish

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on Mårten Lange

Thursday, 10 October 2013

Laura Letinsky

Work from Ill Form and Void Full.

“This exhibition focuses on Letinsky’s new series, Ill Form and Void Full (2010-11), and marks a significant development in her work since 2009. Letinsky became increasingly interested in the artificiality of the photograph and its potential as a self-reflexive space. Here Letinsky has begun incorporating paper cut-outs from lifestyle magazines and art reproductions of food and tableware into her studio arrangements.

The series title Ill Form and Void Full continues Letinsky’s interest in playing with representations of space and time, but departs from the narrative potential of the still life. It focuses on the relation between positive and negative space, and a more muted depiction of a subject where two and three dimensional forms from different sources co-exist uneasily.” – Photographer’s Gallery London

Tags: fotofocus, lecture, meta-photographic, meta-photography, rad, still life

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on Laura Letinsky

Wednesday, 9 October 2013

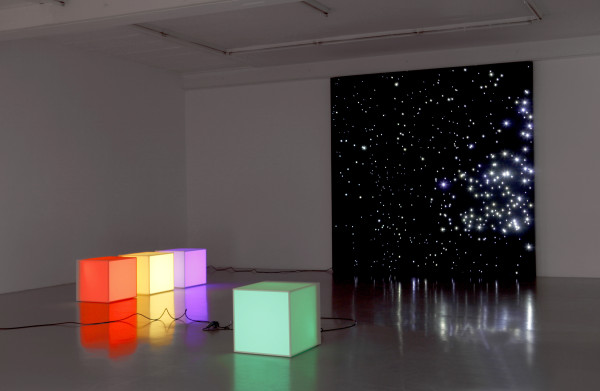

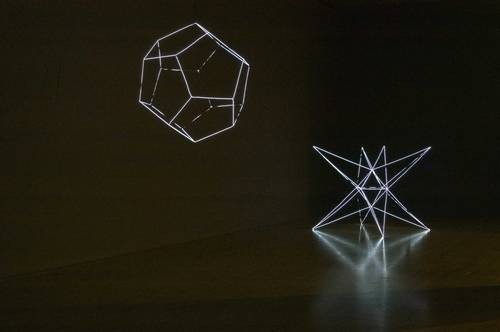

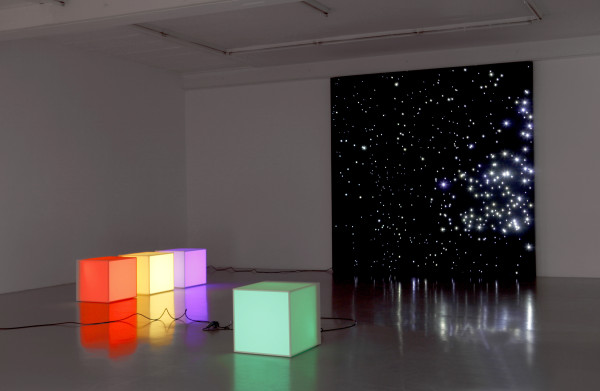

Angela Bulloch

Work from her oeuvre.

“Angela Bulloch is interested in systems that structure social behaviour. Her functional sculptures, light and sound works play with the ways in which we construct and interpret different types of information, be it related to art, literature, cinema, music, or issues of ownership and authorship. Her multi-disciplinary installations marry conceptual rigour with sensuousness and humour. Walking through a room triggers canned laughter; a video screening is activated by a person sitting on a cushioned bench opposite; a wall-mounted sequence of coloured spheres switches on each time a person passes a particular point.

Since the early 2000s Bulloch has been creating increasingly ambitious sculptural installations made from ‘pixel boxes’. Developed by Bulloch with engineers as a prototype in the late 1990s, the pixel box is made up of luminous tubes and an electronic control unit housed within an industrially produced wooden or metal casing. Elemental units within an ever-expanding body of work, the pixel boxes form the basis of a variety of structures, from towers and floors to monumental screens which translate scenes from cinema, television or entirely abstract sequences as mesmerising colour compositions that change before the viewer.” – text via Galerie Micheline Szwajcer

Tags: cube, perspective, pixels, space, yba

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on Angela Bulloch

Tuesday, 8 October 2013

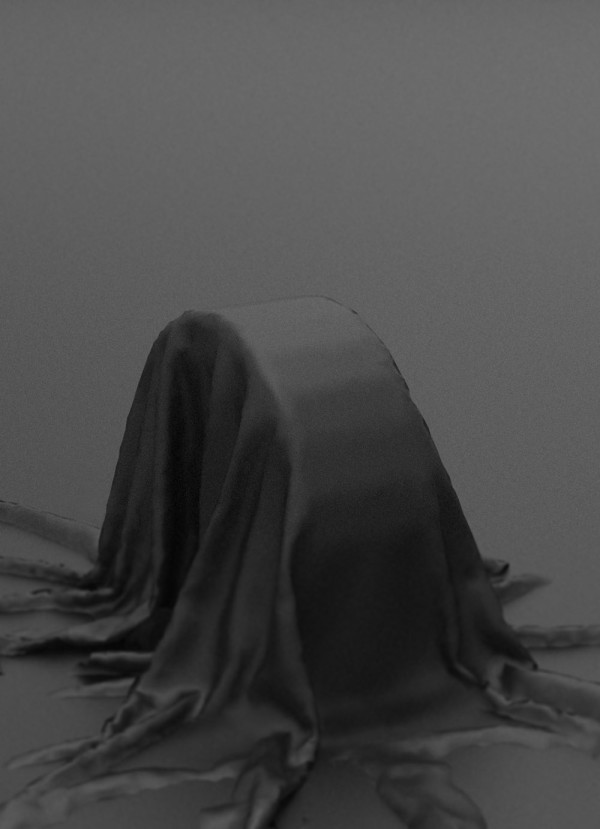

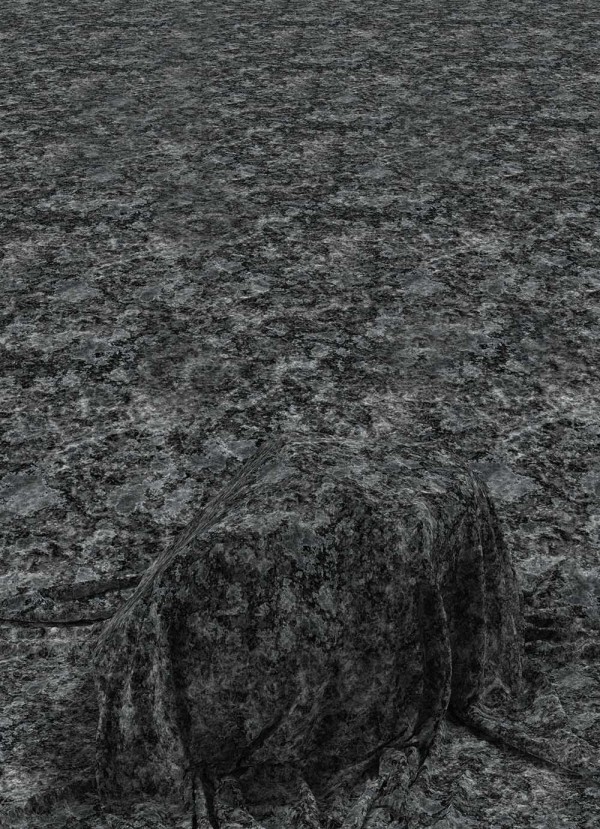

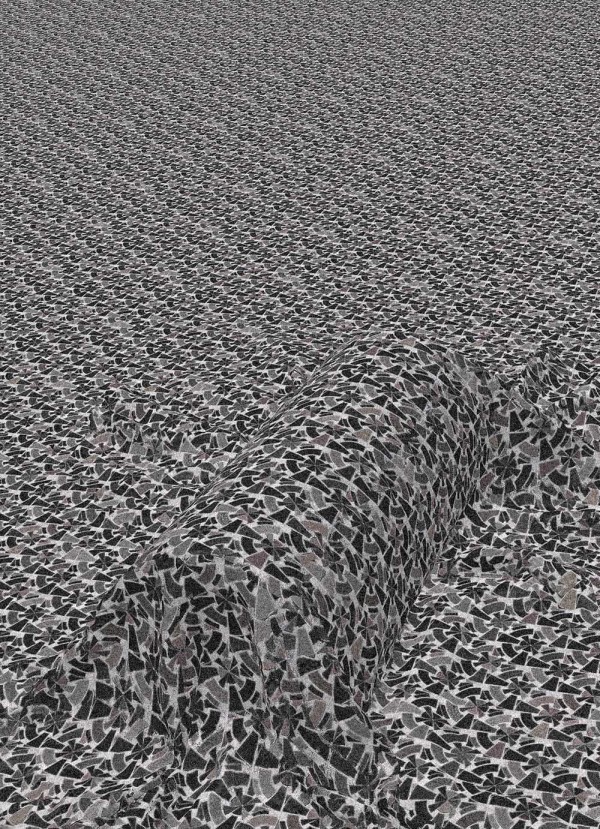

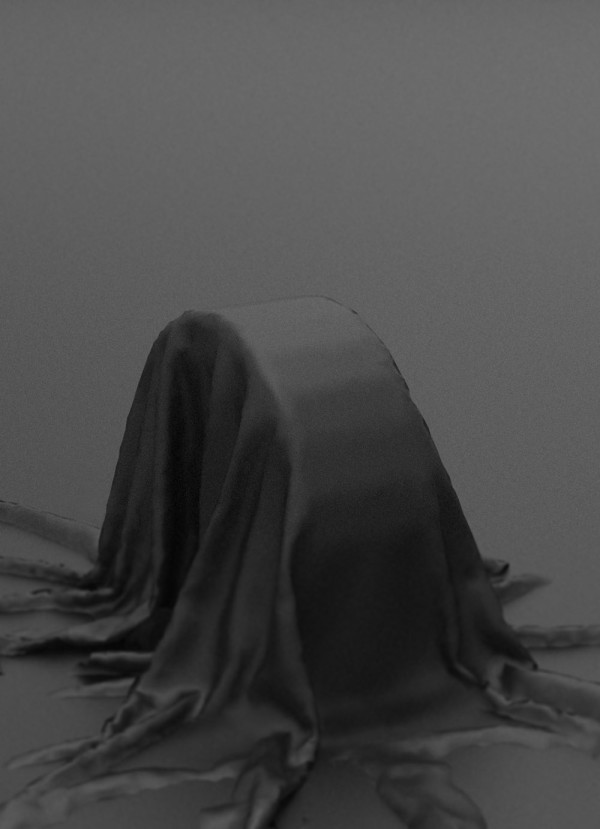

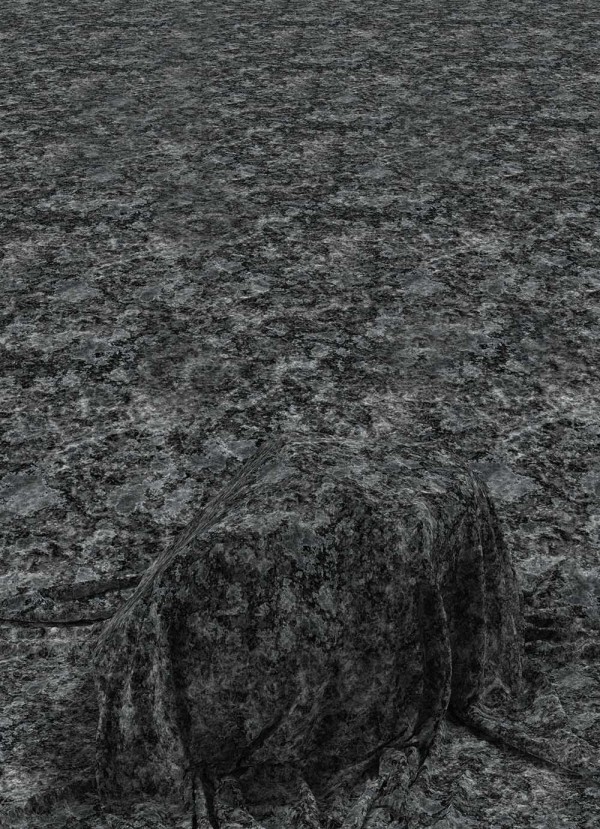

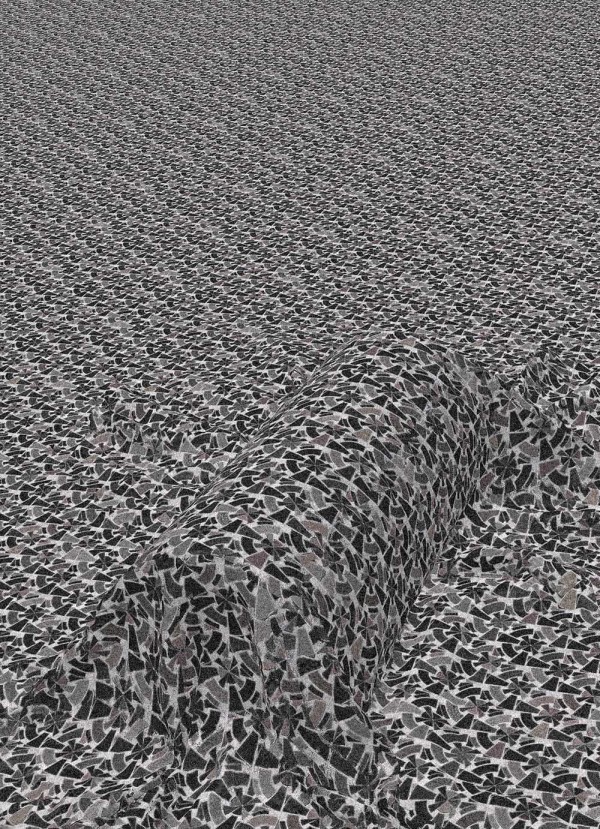

Hugo Scibetta

Work from Draped at Domain Gallery

“Hugo Scibetta’s work reinterpret and reconstruct the information and images ingested through the prism of the screen. From these attempts derive various forms, which are an experiment of composition and confrontation between volatile datas and tangible materials.

The “Draped” series is an evolving and ongoing project.

It is the result of a texturing test on 3D forms through a process

of drape.

The generated images are the finding of a kind of frustration, that of a time spent searching, trying, for a disappointing render.

The aesthetics of failure is then proposed as a new definition of “Beauty”, in which the technical flaw becomes harmonic.” –Domain Gallery

Tags: 3d rendering, data, materials, texturing

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on Hugo Scibetta

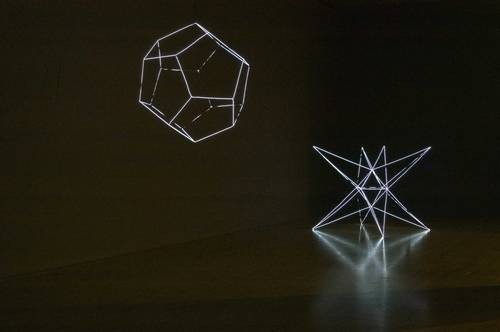

Monday, 7 October 2013

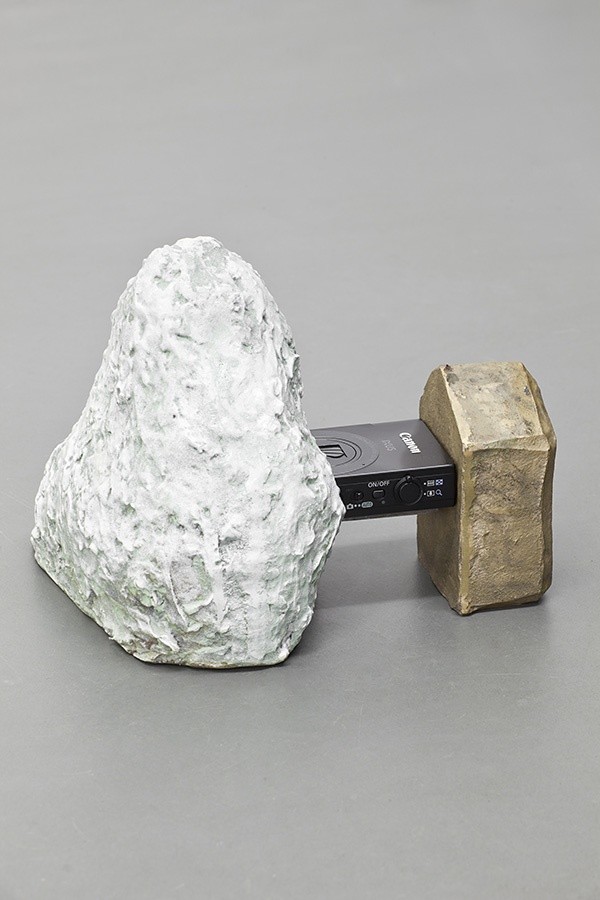

Karl Larsson

Work from “Twelve Hours” at Galerie Kamm, Berlin

“When Foucault enters the amphitheater, brisk and dynamic like someone who plunges into the water, he steps over bodies to reach his chair, pushes away the cassette recorders so he can put down his papers, removes his jacket, lights a lamp and sets off at full speed. His voice is strong and effective, amplified by loudspeakers that are the only concession to modernism in a hall that is barely lit by light spread from stucco bowls. The hall has three hundred places and there are five hundred people packed together, filling the smallest free space … There is no oratorical effect. It is clear and terribly effective. There is absolutely no concession to improvisation. Foucault has twelve hours each year to explain in a public course the direction taken by his research in the year just ended. So everything is concentrated and he fills the margins like correspondents who have too much to say for the space available to them. At 19.15 Foucault stops. The students rush towards his desk; not to speak to him, but to stop their cassette recorders. There are no questions. In the pushing and shoving Foucault is alone. Foucault remarks: “It should be possible to discuss what I have put forward. Sometimes, when it has not been a good lecture, it would need very little, just one question, to put everything straight.” – Galerie Kamm, Berlin

“Twelve Hours” is on exhibit through 26 October 2013

via Mousse Magazine

Tags: objecthood, philosophy, sculpture, swedish, theoretical

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on Karl Larsson

Sunday, 6 October 2013

Alice Channer

Work from Out of Body.

“For her South London Gallery exhibition, British artist Alice Channer has created an installation of entirely new works which extend her exploration of the relationship between the human body, personal adornment, materials and sculpture. In these figurative works, Channer questions established hierarchies within the history of art, objects and clothing, and offers a unique perspective on manufacturing, the hand-made and consumer culture.

Out of Body brings together a group of sculptural works which the artist defines as being figurative, but from which recognisable representation of the human form is as noticeable by its absence as by its presence. It is the tension born of that relationship which weaves a binding thread between pieces made in a broad range of materials, using a variety of techniques and on radically differing scales.

Entering the main gallery the viewer is confronted by enormous digital prints of stone-carved classical drapery, suspended from the impressive height of the space and held to the floor by marble surrogate limbs. The bodily references are direct if not immediately obvious in these works, but less so is the distinction between what is human and what is not. Two other pieces, entitled Lungs and Eyes, span the space in a different way, each one occupying opposite walls, 20 metres in length, in a sequence of aluminium frames which take their forms from Yves Saint Laurent’s drawings for his famous ‘Le Smoking’ suits. Establishing a dialogue between the industrially-produced metal armatures and the artist’s body, every frame has been hand-covered in machine-sewn Spandex sleeves, which have been digitally printed with an ink impression of Channer’s arm, stretched beyond recognition.

Adding to this complex web of relationships between various methods of production and references to the human body, floor-based sculptures entitled Amphibians and Reptilescombine machined, hand-carved and polished marble with aluminium casts of stretch-fit Topshop clothing and mirror polished stainless steel which has been digitally cut and industrially rolled along hand-drawn lines.

In talking about the show, Channer says:

“I am not trying to oppose or find alternatives to the things that separate us from ourselves – the machine, the industrial, the virtual, the commercial. Instead, I am seduced by these things and am becoming part of them through the work. The work is me, breathing, feeling and thinking with, through and as part of the processes and materials that make up the industrial and post-industrial late-capitalist world that I live in and that constitute my work.”…” – text via ArtSlant

via DUST Magazine.

Tags: body, british, classical, Dust Magazine, hanging, material, scroll, sculpture

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on Alice Channer

Saturday, 5 October 2013

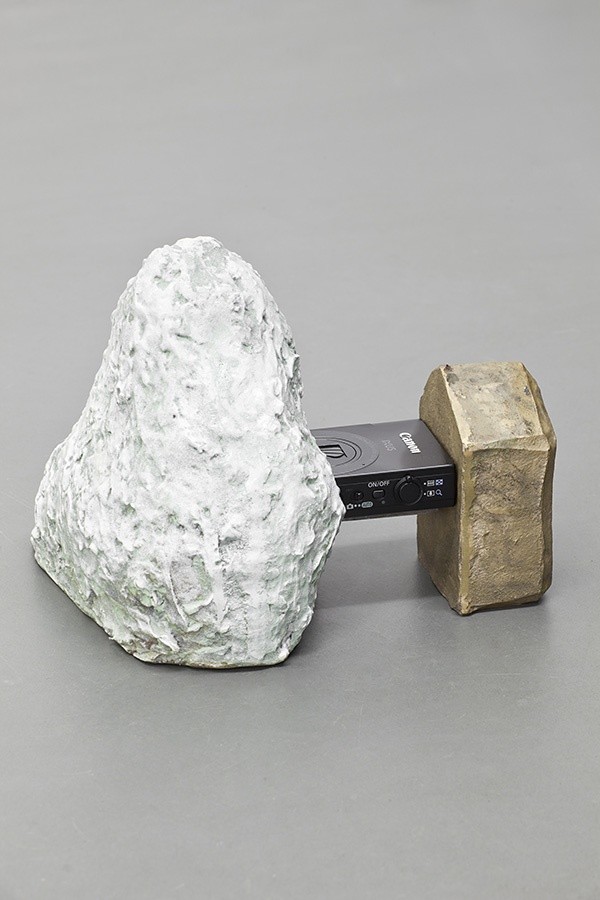

Jon Rafman

Work from You Are Standing in an Open Field.

“…Journeys through virtual landscapes form the heart of Jon Rafman’s current show, expressing his continuing search for lost loves, ideals and cultures. Alongside this, Rafman foregrounds his ongoing exploration into the nature of memory conveyed through intimations of archaeology and anthropology, highlighting the way that we rely on objects to locate our relationship to the past. Sculpture, video, and mixed media installation express the material form that memory takes.

The historical impulse to make sacred what is lost becomes all the more urgent when we consider contemporary technologies and online cultures. Rafman encases not-yet-vanished cultures in the form of sham relics or false monuments in order to both recognize their historical value and to critique contemporary amnesia. In his works, ephemeral cultures meet the solidity of constructed artifact. In Rafman’s version of archaeology, a large finely engraved stone carving commemorates not fallen war heroes but the names of defunct New York state shopping malls. By using sham ruins to evoke an historical gaze on these contemporary cultural objects, Rafman changes the meaning of both and raises the question of what exactly we are remembering when we visit a museum, when we look at a memorial, or when we click on a broken web- link…” – via Zach Feuer Gallery

Tags: bust, chelsea, digital, digital culture, edits, new media, video game

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on Jon Rafman

Friday, 4 October 2013

Joel Dean

Work from The Mutant and the Melody at Jancar Jones.

The show takes its structure from the dichotomy of an ancient form of cultural inheritance, the fable. It includes two pieces that remain in flux for the full duration of the exhibition. Like the driving forces in the narrative of a fable, the pieces work together to perform a story from which the audience can extract a pithy maxim about shared human consciousness. Historically fables present morals. The wording of a moral may differ between cultures, and how a fable is recited may shift over time, but the lessons presented in fables are universal. They reflect a cross-cultural consensus of the human experience.

The history of the fable is, up until the industrial revolution, mostly an oral history. The fables we have today were arrived at over time through verbal re-duplication. They evolved in a manner analogous to the self-replication of a meme. Fables exist both as images and as stories, but they also relay behaviors. They are one of the first user- generated structures for sociocultural imitation, and can serve as a model for understanding the shifts in information hierarchies that are occurring throughout society as our globalized economy moves away from a packaged good media towards a conversational media.

To highlight this connection, and to emphasize dialogue over dogma, The Mutant and the Melody presents two maxims that have recently been transformed into mantras through their extensive use on social networking websites. Neither maxim is the moral of the story. Instead, they operate as a call and response, working together to frame a key paradox facing the content generation: it is impossible for an individual to exist in a state of pure spontaneity while also working to document that existence.” – via Jancar Jones

Tags: color, gradient, installation, LA, painting, rocks

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on Joel Dean

Thursday, 3 October 2013

Tobias Kaspar

Work from Bodies in the Backdrop at Galerie Peter Kilchmann.

“The Galerie Peter Kilchmann is pleased to present the first solo exhibition of Tobias Kaspar (born 1984 in Basel) in Switzerland. The artist lives and works in Berlin and belongs to a young generation of artists who work with strategies of conceptual and appropriative art.

The exhibition shows the installation Bodies in the Backdrop (2012) which is composed of 20 color photographs, and a slideshow with separate sound, which was initially shown at the Halle für Kunst Lüneburg in early 2012. Correspondingly, a catalog of the same name was published by Walther König Verlag, Cologne, and is now available at the gallery. The title, inspired by Elizabeth Lebovicis text about Ghislain Mollet-Viéville, points to the affective and economic relationships of tensions between collectors and other actors in the field of art. The photographs document a visit to the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice and how heaviliy cropped, itʼs main protagonist being a young girl and boy, different works and unknown visitors. These scenes are accompanied by quotes like “I especially hated people making love on my bed“ (see invitation card), or “I could not produce the sum necessary because all my money was tied up in trusts“ from Peggy Guggenheim’s autobiography «Confessions of an Art Addict», which have already a strong narrative quality…” – Galerie Peter Kilchmann

Tags: appropriation, archive, berlin, carpet, found image, swiss, tv, video

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on Tobias Kaspar