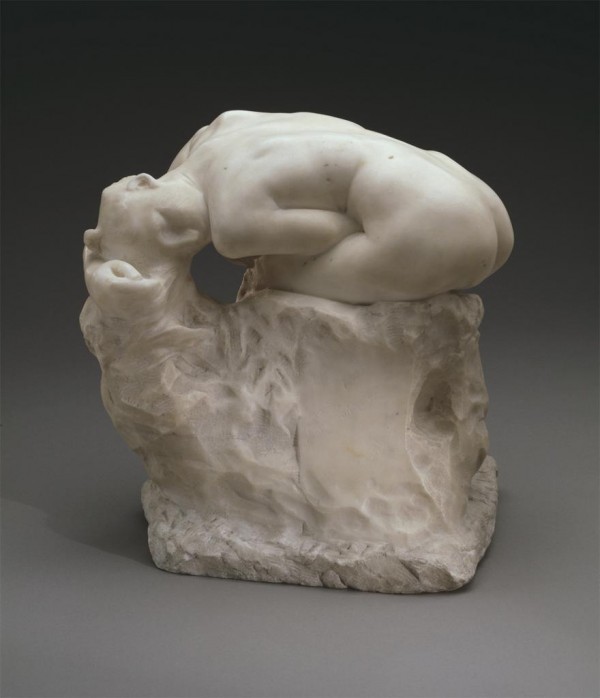

From top to Bottom: Small Seated Female Torso (N.D.), Hand of Dumas (N.D.), Andromeda (before 1917), Hands Clasping (N.D.)

“Born to a working-class family in Paris, and despite promising talent, Auguste Rodin (1840–1917) struggled hard to obtain the international fame he would enjoy by the 1890s. After repeatedly failing to gain admission to the prestigious Ecole des Beaux-Arts, he supported himself as a decorative object craftsman and studio assistant. His sculptures from this era were radically different from traditional idealized figures—an indication of the rugged, realistically imperfect forms that would characterize his signature style.

Rodin finally gained state patronage in 1880 after a group of artists petitioned the government to provide him with a studio, financial support, and official commissions for public sculptures, many of which he failed to finish. One such project was the bronze doors known as The Gates of Hell. This unrealized masterpiece obsessed the artist until his death and spawned numerous sculptures enlarged from its figural elements.

Bewildered by their rough edges, tool marks, and lack of finish, the public often considered Rodin’s sculptures unacceptably incomplete and frequently obscene for their sexually charged nature. Nevertheless, Rodin achieved fame and status by the turn of the century. In his groundbreaking modernity, he laid the foundation for twentieth-century masters such as Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and Constantin Brancusi.”

-Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden