Heimo Zobernig

Work form his oeuvre.

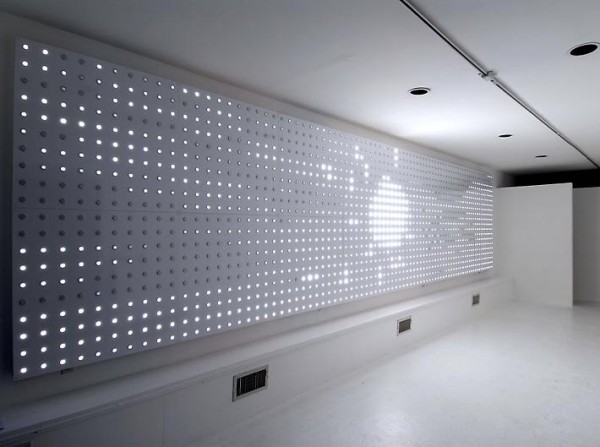

“Zobernig’s main interest often seems to be attempting to find out what the bare minimum requirements for a work of art or art space might be. His installation O. T. (Untitled, 1999-2000), for example, is a press conference, podium discussion and video presentation space with rows of white designer chairs, a long Last Supper-type table and audio-visual hardware between two floating panels in black and white. Three monitors showed some of his rather bland low-tech videos. The room is something of a reprise of similar earlier works, including his conference room design for Documenta 10, with Franz West chairs. But it could conceivably be customized for the reception or promulgation of international art in any institution anywhere. Sitting in the room is like being at an absurd discussion that has no participants or invited guests but is taking place anyway.

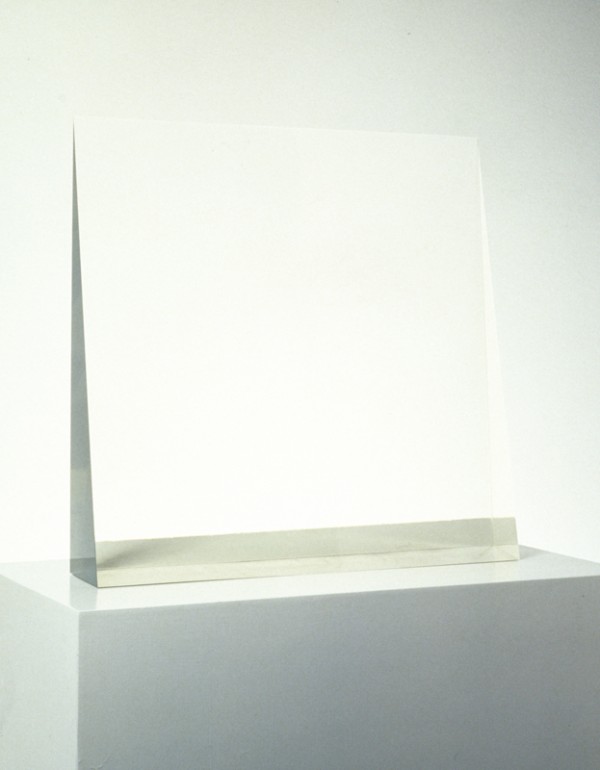

Zobernig’s most dramatic commentary on architecture for art was in the cavernous gap that divides the interior of the new museum into two lopsided grey basalt-clad lobes. Here he installed his White Cube (2002), a permanent intervention that acts a passage or connection between the exhibition rooms on one of its levels. It is a kind of gesture equivalent to a reverse lobotomy. Like Blinky Palermo’s site-specific paintings in art institutions, it is easy to miss if you haven’t been in the place before, although in a typical piece of showmanship Zobernig organized a spotlight projection of his name and the work’s title. Also on show were displaced reconstructions of similar works, such as Kunstmesse Chicago, 1990, Stand Galerie Peter Pakesch (Chicago Art Fair, Peter Pakesch Stand, 1990), (1990) a gallery booth for the Chicago art fair, and a chipboard reception area and a doorway for the Neue Galerie, Graz – O. T. (Untitled, 1993). Although many artists have explored the boundaries between sculpture and architecture, display techniques and furniture, Zobernig does it with considerable finesse.

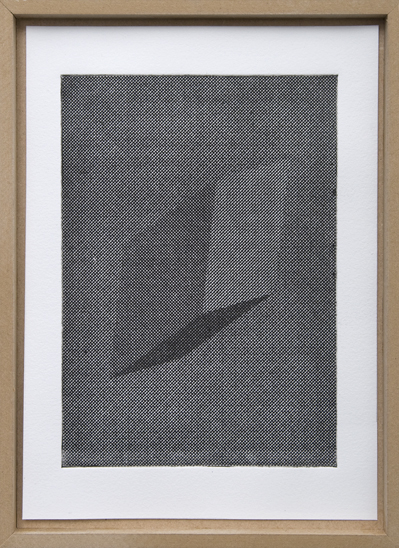

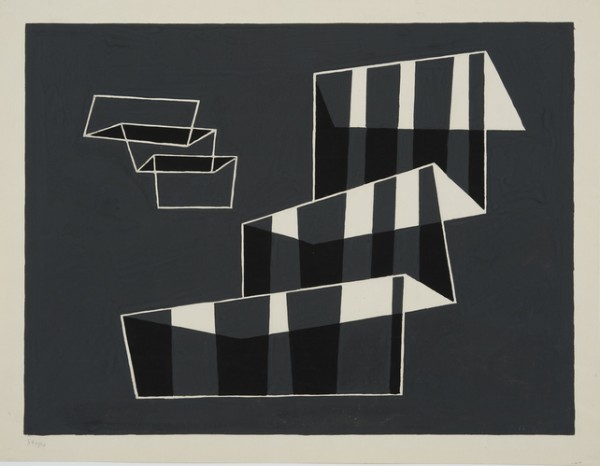

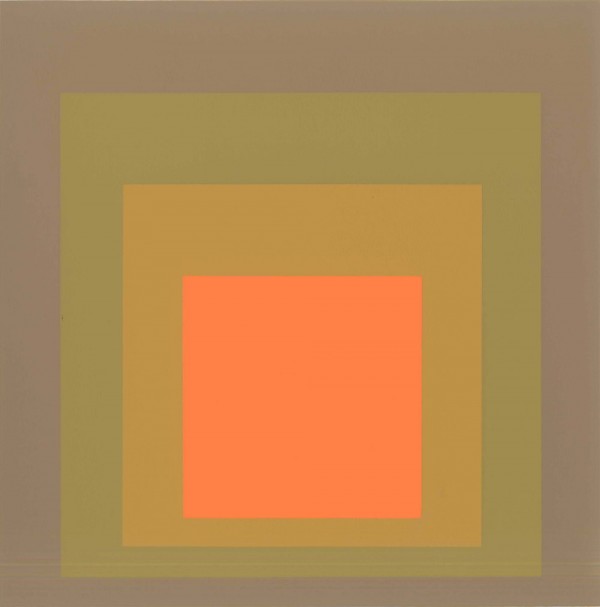

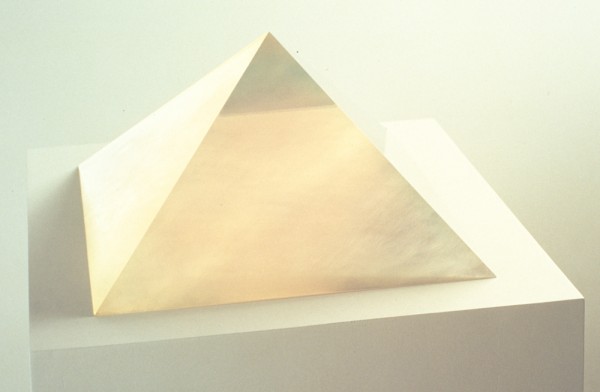

The hallmarks of his work is his use of standard materials and sizes, an inside-out appearance and the embracing of a no-frills craftsmanship that acts something like the equivalent of brushmarks and rough edges in some of his paintings and sculptures. This is evident in his great gloss-painted cardboard objects such as O. T. (Untitled, 1986), a tarred and feathered column or pedestal. Included in ‘Mid-Career Survey’, were four untitled groups of geometric abstract paintings from the mid-1980s, one of which was hung on a black wall – a reconstruction of an exhibition at Galerie Peter Pakesch, Vienna (Nachbau der Ausstellung in der Galerie Peter Pakesch, Wien, 27.1. – 23.2.1985, 2003). Also included were his works from the mid-1990s, which proclaim the word ‘real’ in the manner of Robert Indiana’s Love; somehow these look better reflected in the untitled mirror works he has made over the years – wall-mounted panels cracked by the blow of a hammer.” – Frieze Magazine