Michelle Forsyth

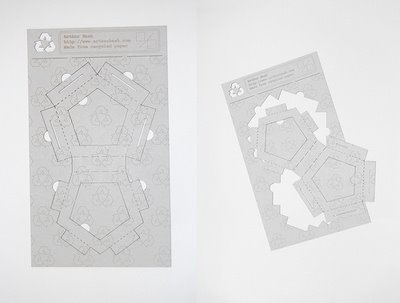

Work from Text Work.

These pieces are made by punching out small circles of paper in a way that replicates the print pattern of a newspaper press. Forsythe’s other work has a conceptually similar approach, using tedium and repitition to force reconsideration of contemporary imagery.

“For the past several years my work has addressed historical events as seen through the lens of news media. Through first-hand visits to, and subsequent renderings of, my visual experiences at 100 historical disaster sites pictured in news photographs, I have worked to address a sense of grief. While researching each site for this project, I have scoured many old newspapers for written information. Along the way I have noted many poetic passages that conjure graphic images of their own. In Text Work, I have punched several quotes, including eyewitness testimonies and first-hand accounts, into single sheets of white paper. What is left is a lacey absence.”

____________________

“Favoring the formal elegance of pattern, and the visceral qualities of the handmade over the efficiency of digital production, I consider my work to be a reflection on, and a reaction to, the onslaught of images of suffering in our contemporary world.

All of my work is made in response to an extensive collection of images of trauma culled from television, newspapers, and the Internet. From horrific scenes of disaster captured by our contemporary news media to the smaller scale depictions of personal tragedy, images of peril and demise have permeated nearly every aspect of contemporary life. Even without the recent documentations of the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, the US invasion of Iraq, or the Israeli bombing of Lebanon, it is easy to see that the mass media pushes daily reminders of the aesthetics of horror. Viewing these kinds of images from afar creates ways of looking that are, at once, both voyeuristic and apathetic. As I find myself confronted by this onslaught, I mourn our tolerance of violence in our media and our inability to express a sense of grief. “To grieve,” according to Judith Butler, “and to make grief itself into a resource for politics, is not to be resigned to inaction, but it may be understood as the slow process by which we develop a point of identification with suffering itself.” (See Judith Butler, Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence (New York, Verso, 2004), p.30).

As a humanistic response to these kinds of tendencies, I transform images of abjection and spectacle into glittering surfaces that shroud the images of pain with layers of beauty. Quiet and contemplative, my work bears traces of its making. From thousands of tiny, sinuous brush strokes or cut-out paper flowers, to diluted layers of watercolor, the value of my time spent becomes just as important as the final product. Color functions to conceal and hide the images in a protective coating, which creates a distance that I hope will empower viewers with a greater ability to bear witness to the complexities of our mediated experience.

I am certainly not the first painter to respond to these kinds of horrors, nor am I the first to work from journalistic photographs as source material. From as far back as Francisco Goya’s Disasters of War series (1810 – 20), which document the horrors of the Napoleonic invasion of Spain in 1808; and Edouard Manet’s The Execution of the Emperor Maximillian (ca. 1867) depicting Mexican republicans executing the French appointed emperor; through Gerhard Richter’s suite of 15 black and white paintings of the imagery associated with the Baader-Meinhof gang, who all committed suicide in their prison cells early on the morning of 18 October 1977; and Leon Golub’s paintings documenting the atrocities of the War in Vietnam; to the more recent work by Joy Garnett and Adam Hurwitz, the physicality that painting holds has long provided us with means to reflect on the persistence of these kinds of atrocities. According to Susan Sontag, “Torment, a canonical subject in art, is often represented in painting as a spectacle, something being watched (or ignored) by other people. The implication is: no, it cannot be stopped – and the mingling of inattentive with attentive onlookers underscores this.” (See Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003) p. 42.) Although I consider my work, as a whole, to fall within this tradition of painting, it does not rely on the aesthetic spectacle to give it its power, instead I hope it will be a lasting counterpoint to the typical manner in which we view traumatic historical events.”