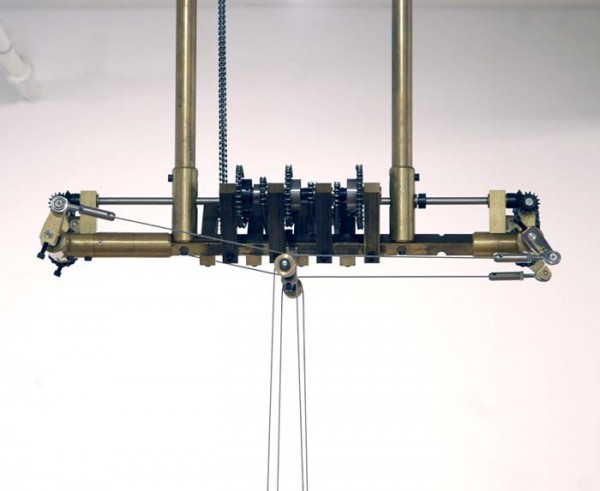

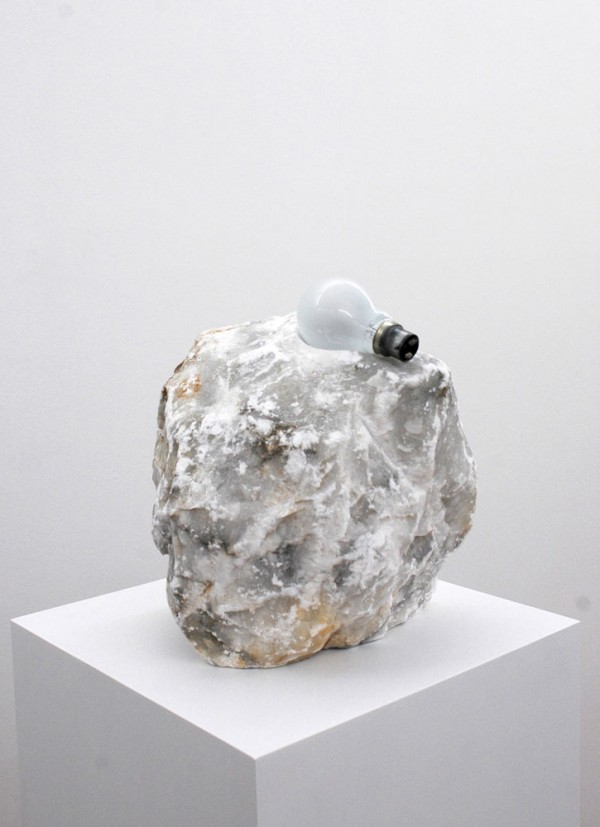

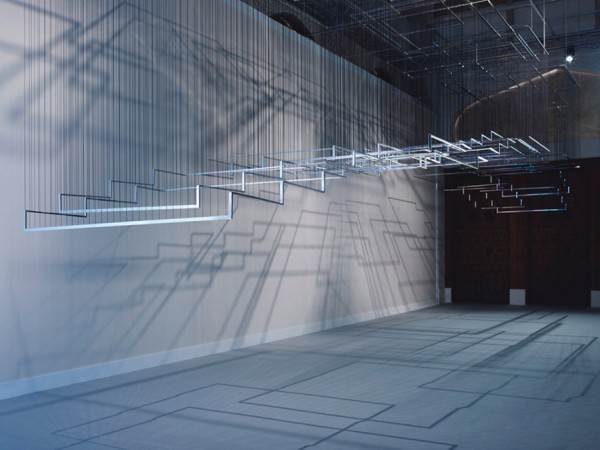

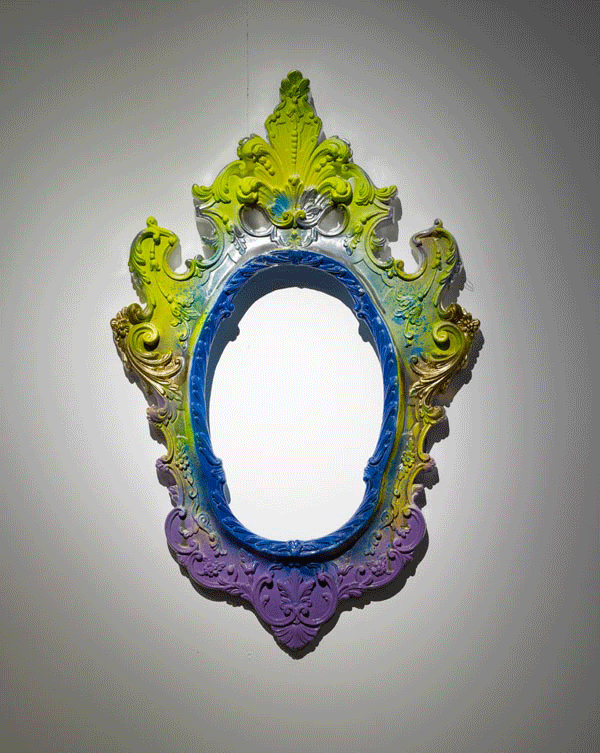

Work from To Dust.

” Two sculptures are hung from a mechanism that gently grinds them into each other. The sculptures will slide against one another for many years creating new unimagined form…

…The Shortcomings of the Living World’s Experiences vs. The Infinite Potentialities of The Universe, A DEATH CATHARSIS PARADIGM

The thrill of the Cyclone is an old thrill. Bull Fights. …Aztecs… Standing in line under the aged wooden roller coaster on Coney Island, hearing the creaking of the wood under the barreling weight of the heavy cars, the screams of the groups in freefall… waiting, looking up: you have already entered into the ritual.

Tension builds as the crowd salmons through the slots into fate-chosen cars. The platform shakes deep and heavy, connecting to an unseen force. To wait in line, to watch, to anticipate – is to participate. Anticipation is part of the experience. When your moment comes, you step into the car. And the larger than life force of the mechanism catches you up and hurls you over a precipice. The pure natural force of gravity slips you terrifyingly up out of your seat, as the machine drags you even faster against it: down. Two jealous gods do battle over your mortal body. To ride the Cyclone is to be swept up in the center of the narrative. Ulyssian adventures of life and death are in action upon you. In the end, through the dark, the car rushes home and is impressively and abruptly stopped. The firm hand of force is finished with you, done. The door is rudely shown to all. “Get out.” It is over. You walk out on wobbly newborn legs a changed man – giddy – full of life.

Thrilling or nauseating the rollercoaster is built to have a physical effect. What is this about? Why take fate in hand for fun? Interacting with elemental bodily fear, and transforming that fear into a feat, changes your relation to the world.

Surprising your autonomic functions, scaring the hell out of your reptilian brain, is fun.

For once you are the older brother of the autonomic, you know more than it does, you alone are privy to the knowledge of your fate. Why not fake it out, give it a shock, silence it for a while? For once, you can override its chronic, nagging suspicions of doom. Why not discharge your automatic brain so it doesn’t run you. So you run it.

It is a primal bodily catharsis to throw yourself onto the Cyclone. You take the tension of fear and combust it, convert it out into the universe. The pressure is released. Ritual is a very old reset button. The function of all ritual is catharsis.” – Jonathan Schipper