Gilles De Brock

Work from Liquid Design and The New Public Space

“Liquid Design

Imagine, you’re living in the 14th century, somebody tells you the printing press will be a catalyst in a scientific revolution. You would probably think this person is exaggerating. You do understand the principle of reproduction and distribution of thought, that’s not the problem. However, you can’t imagine that such a simple thing as a change in medium can have such a profound impact.

The inability to understand the transition to a newer medium can have severe influences. From the moment the printing press made it’s first appearance a new group of disadvantaged became apparent, the illiterate. This group was unable to read, spell and write and could therefore not interpret the new medium. For them the world became more and more a place they could not understand.

In the 21st century not only the illiterate are the ones that are unable to understand the new current medium. A new group is created, those who can not understand an ever changing medium. With the arrival of the internet it becomes relevant to ask if a human being and the graphic designer can really cope with an ever such changing medium.

The modern illiterate

There is a new group of disadvantaged because of the nature of a developing or established medium. This, in essence, is what happens with every new medium, as it asks of it’s user to undergo a process of unlearning and learning. Besides vocal language, people had to learn how to interpret written language, they had to unlearn to write the same as they spoke and refinements were expected along the way .

But what happens if a new medium is introduced that is not only different from it’s predecessor but also constantly changing? The process of learning and unlearning becomes a constant state. Alvin Toffler wrote the following about this:

“The illiterate of the 21st century will not be those who cannot read and write, but those who cannot learn, unlearn, and relearn.”

If we take a look at which medium might be the biggest change towards the printed word, the internet is likely to be picked. Our environment is more and more designed for quick communication in which we are hardly limited to geographical location, our social relations are maintained by platforms and applications and the amount of people that use smartphones, tablets and laptops is growing exponentially. All developments largely dependent on the internet.

With our daily and sometimes even uninterrupted use we give ourselves the interpretation that we also understand. We use a smartphone so we “are” on the internet, we use google so we use the internet. But do we truly understand what internet is? Is using applications that are on the internet the same as understanding? Maybe we are fooling ourselves, and maybe we are the new generation that does not understand it’s environment. And perhaps worse: we aren’t even noticing it.

From solid to liquid

An important cause of if we do or do not understand the internet is most likely the wrong interpretation of it’s nature. Up until we had internet all our media was invariable, as soon as they were produced. A book, newspaper, flyer or poster: as soon as they are produced they are solid. The internet on the other hand is not solid at all. For example news-websites can add and change content at any moment of the day. If you look at a news website you merely see a snapshot of an ever changing image. But if internet knows no solid state which state does it have then? Maybe liquid?

In core the difference between solid and liquid is easily described, however it is very clearly defined by Zygmunt Bauman “[…] in simple language […] liquids, unlike solids, cannot easily hold their shape. Fluids, so to speak, neither fix space nor bind time. While solids have clear spatial dimensions but neutralize the impact, and thus downgrade the significance, of time (effectively resist its flow or render it irrelevant), fluids do not keep to any shape for long and are constantly ready (and prone) to change it; and so for them it is the flow of time that counts, more than the space they happen to occupy: that space, after all, they fill but ‘for a moment’.

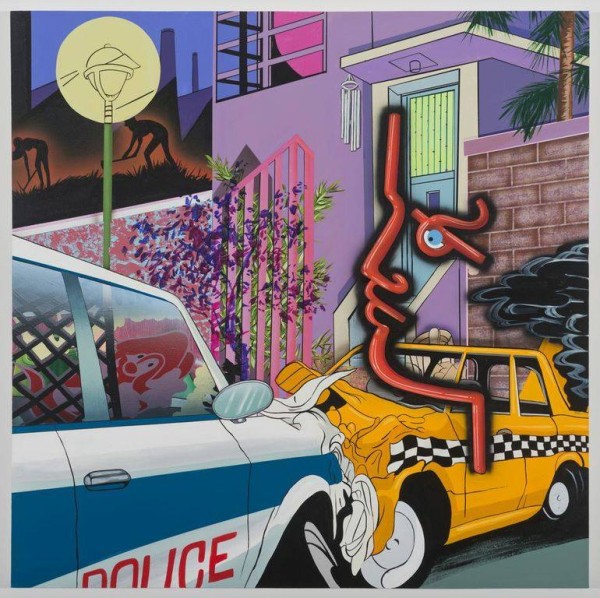

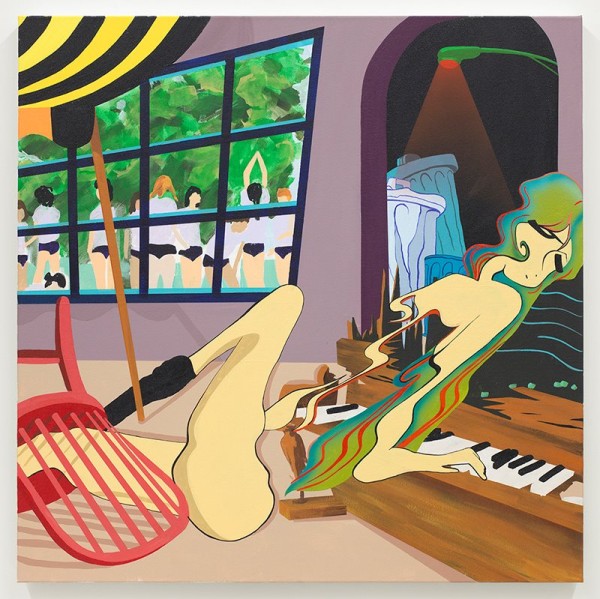

Not only the visual qualities but also time plays an indispensable role. A picture of a liquid form needs a time indication, because when the picture is taken, the liquid form has already changed. A solid shape however is hardly affected by time. As easy as liquid shapes change they manoeuvre around solid shapes and hardly feel impact. They can ‘flow’, ‘spill’, ‘run out’, ‘splash’, ‘pour over’, ‘leak’, ‘flood’, ‘spray’, ‘drip’, ‘seep’ and ‘ooze’. Even better, just as it takes energy to hold a liquid form stationary, it takes energy to make a solid form move.

The comparison between solid and liquid is highly relevant when we are talking about internet. The internet doesn’t know the solidness as we have known in media up to now. The internet does not feel any friction when being moved: it flows from one side of the world towards the other in a fraction of a second. Images can be duplicated with a friction that is almost negligible. News-reports don’t have a specific moment in time they are only snapshots of a liquid form.

Liquid Design

The underestimation of changes and their impact, and the wrong interpretation of the nature of the internet, can have profound effects, as Toffler indicated: the rise of a new generation that can’t interpret the media around itself. Especially because of these factors it is very important to address a group that is extremely dependent on the medium of this time and it’s interpretation: the graphic designer.

The printing press was on it’s own nothing more then a technique; it was the human who by a (specific) implementation gave value to it. He duplicated documents, made books, made posters, flyers and derivatives. From this development the graphic designer evolved, a person who has the task to visualise a message in the media of it’s time.

Here arises a paradox: graphic designer is rooted in history of solid forms, but it’s his task to use the medium of nowadays which is mainly liquid these times. Because the medium is so different, omnipresent and growing, it is the graphic designer who should critically review himself. The graphic designer must go from solid (static) design towards liquid design. We shouldn’t learn to write and read differentially in order not to become subordinated; we need to learn a skill to handle constantly changing state of our new media. This is not a simple task for a graphic designer, because he is inclined to think in terms of solidness, rules and grids. It is almost an inhumane transition. It is in our nature to think in heuristics in order to make our daily life manageable: who are and are not our friends, what I do and do not like, etc.

Maybe the transition to liquid design is still ungraspable and we should take a step back and realise that we underestimated the internet, it’s nature and impact. Even language limits us.

Comprehending, grasping, materialising are conceivable descriptions of a change in thinking in which statements are made in terms of solidity.

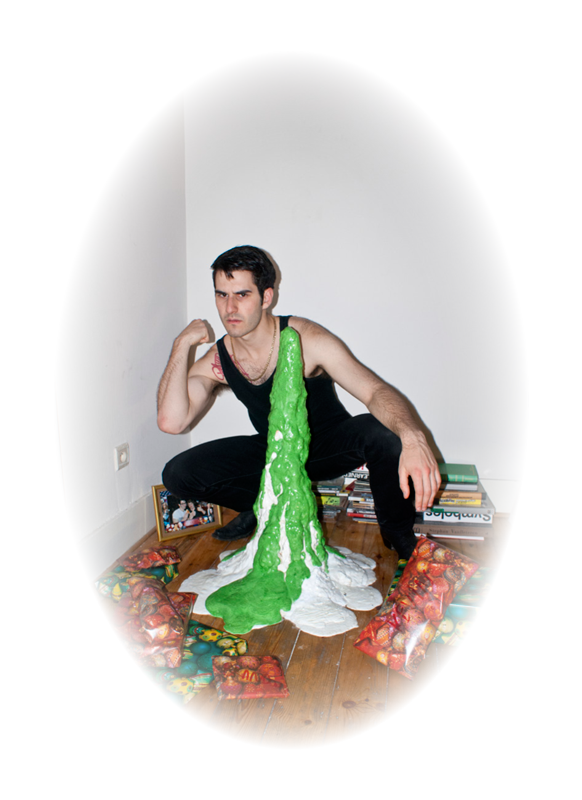

Factors like these make it an excellent task for a graphic designer to rove the internet in a visual way. By not only understanding it and holding it down but also by letting it ‘flow’, ‘drip’ and ‘ooze’.

The New Public Space

If posters can be created on demand, what does that mean to our perception of them? This project is an experiment on a poster that refreshes itself endlessly to current relevant matter. Can we design a poster that shows an interpretation of the current world at all times? And what happens when you do, can this application be thought of as a representation of the future?”