Work from Self Portraits.

“On Dec. 8, 1980, Tseng crashed the opening reception for an exhibition of Ch’ing Dynasty costumes at the Metropolitan Museum. By this time, Tseng had affected a military haircut and added to his costume a small photo identification card. (The words printed on the card, “Visitor” and “Slutforart,” would have blown Tseng’s disguise, but few people ever noticed them.) As the rich and famous arrived, Tseng invited them to pause for photographs and take part in brief conversations which he recorded. Among those snapped posing with Tseng were Henry Kissinger, William F. Buckley, Jr., and Yves Saint Laurent, who commended Tseng for his fluency in French and asked if he had served in the Chinese embassy in Paris.

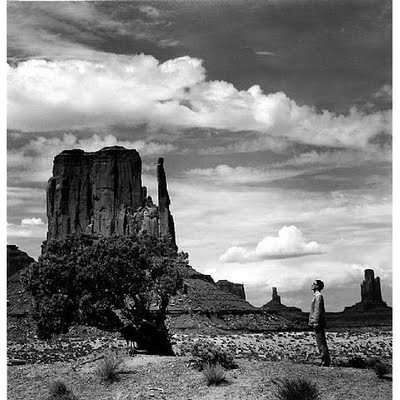

That night at the Met, Tseng tapped into something rather profound: the pervasive ignorance of Westerners regarding Asia generally and China specifically. More than just a brilliantly executed hoax, Tseng’s unauthorized appearance at the museum opening was a concise critique of “Orientalism.” It was also a significant moment in the evolution of an artist. From 1979 until his death from AIDS in 1990, Tseng used the persona of an anonymous visiting Chinese government functionary to create an oeuvre that explored and exploited Western stereotypes of Asians. Initially titled “East Meets West,” Tseng’s primary body of work consists of approximately 150 black-and-white photographs, each of which shows the artist, in costume, posing in front of such American tourist meccas as Niagara Falls and Mount Rushmore. After 1983, Tseng went international by photographing himself at sites such as the Eiffel Tower, Tower Bridge in London and the statue of Christ that overlooks Rio de Janeiro.

More concerned with staging a one-man invasion of familiar images than with seeking new perspectives on cliched national icons, Tseng determined the location for his camera by scouting out the most popular tourist views. Wearing his gray Mao suit, ID badge and sunglasses, Tseng posed rigidly with the camera’s shutter release held firmly in one hand, the release cable visibly trailing back to the camera. In the photographs, his expressionless face and clenched fist are vaguely menacing. This menace is subtly reinforced when the camera angle makes Tseng appear to dwarf such monuments of American gigantism as the Empire State Building or the Hollywood sign.

Like the sites where he posed, Tseng became an icon, caricaturing the West’s nightmare of “Yellow Peril,” the dread of being overtaken by anonymous Asian hordes that has been a persistent racist subtext of East-West relations for a century. Coinciding with the beginning of the Reagan era, his early images also seemed to playfully mock the ponderous Cold War, anti-Communist rhetoric then being revived. Throughout the series, Tseng’s alter ego was perfectly realized: impassive and unspecific, he satisfied the basic stereotypes by which Westerners define Asia…” – Grady T. Turner for Art in America