Richard Prince

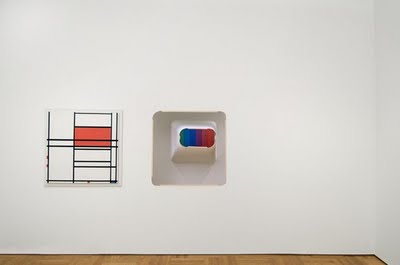

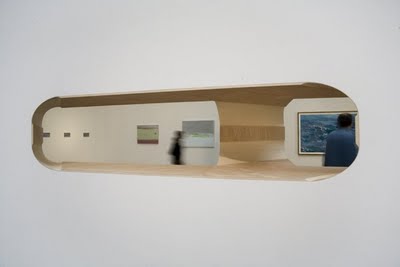

Work From Untitled (Publicities).

“Richard Prince has heard America singing, and it is not in tune. The paradoxically beautiful, seamless 30-year survey of his work at the Guggenheim Museum catches many of our inharmonious country’s discontents and refracts them back to us. The central message of this array of about 160 photographs, drawings, paintings and sculptures, most of which incorporate images or objects cribbed from popular culture, is that we won’t be getting along any time soon. But in Mr. Prince’s view, little of life’s cacophony is real except the parts deep inside all of us that are hardest to reach.

Mr. Prince has devoted his career to this surface unreality, attempting to collect, count and order its ways. He has said that his goal is “a virtuoso real,” something beyond real that is patently fake. But his art is inherently corrosive; it eats through things. His specialty is a carefully constructed hybrid that is also some kind of joke, charged by conflicting notions of high, low and lower.

Frequent targets include the art world, straight American males and middle-class virtue, complacency and taste. His work disturbs, amuses and then splinters in the mind. It unsettles assumptions about art, originality and value, class and sexual difference and creativity.

The work in the Guggenheim exhibition opening today, subtitled “Spiritual America,” defines the nation’s culture as a series of weird, isolated subcultures — from modernist abstraction to stand-up comedy to pulp-fiction cover art — and gives them equal dignity. It begins on the ground floor with “American Prayer,” a magnificent, haunting new sculpture for which the chassis of a 1969 Charger, a classic muscle car, has been stripped bare and cantilevered above the floor by a large block that merges with its hood. As aerodynamic as a bird’s skull and as commodious as a double coffin, it is not on blocks but lodged in one, like a stray bullet. Its bulky support suggests a pedestal, a Minimalist box, an anchorage and an altar. It is spackled and Bondoed, ready for its final, shiny coat, unlike the rest of the car. Together they form a memorial to custom cars presented as an abstracted body awaiting resurrection or a truncated crucifix lying in state.

Mr. Prince’s ancestors include Duchamp, Jasper Johns and especially Andy Warhol. But unlike Warhol, he is much less interested in the stars than in the audience. Thus he is just as much an heir to Walker Evans and Carson McCullers, with their awareness of the common person.

Over the years, Mr. Prince has shown himself to be in touch with the same shamed, shameless side of America that gave us tell-too-much talk shows, reality TV and the current obsession with celebrity. Practically every last American could find something familiar, if usually a bit unsettling, in his work. If he were the Statue of Liberty, the words inscribed on his base might read: Give me your tired, your poor, but also your traveling salesmen and faithless wives; your biker girlfriends, porn stars, custom-car aficionados and wannabe celebrities; as well as your first-edition book collectors (of which he is one).

It often seems that Mr. Prince has never met a piece of contemporary Americana he couldn’t use. Customized checks with images of SpongeBob SquarePants or Jimi Hendrix? He pastes them to canvas and paints on them. Mail-order fiberglass hoods for muscle cars? He hangs them on the wall — instant blue-collar Minimalist reliefs. Planters made of sliced and splayed truck tires? There’s one at the Guggenheim, cast in white resin, where the fountain should be. Is it a comment on the work of Matthew Barney, a gallery-mate who had his own Guggenheim fete? Probably. But from above it resembles a plastic toy crown or the after-splash of milk in that famous stop-action Harold Edgerton photograph.

And borscht belt jokes? They are a signature staple that runs rampant in the show, appearing on modernist monochromes, on fields of checks and as arbitrary punch lines for postwar New Yorker or Playboy cartoons. These examples of a better class of humor are variously whole, fragmented, steeped in white or piled into colorful, nearly abstract patterns yet still retain their familiarity. The same jokes occur in different works, alternately writ big or little, sharp or fading, straight or rippled as if spoken by someone on a bender.

“My father was never home, he was always drinking booze. He saw a sign saying ‘Drink Canada Dry.’ So he went up there.” “I went to see a psychiatrist. He said, ‘Tell me everything.’ I did, and now he’s doing my act.”

Mr. Prince’s act has been one of continual breakouts and surprises, some better than others, and of increasing command. Selected and expertly installed by Nancy Spector, the Guggenheim’s chief curator, with considerable input from Mr. Prince, the show includes examples from nearly 20 series of works, but it also skips a lot of weaker efforts, tryouts and rehearsals. It sums up more than recounts the path of a brilliant artist whose sense of visual style is matched by an ear for language, as he progresses from hip, hermetic mind games to hip, inclusive generosity and even tenderness.

Mr. Prince was born in the Panama Canal Zone in 1949 and has shown in New York since the late 1970s. He is a leading member of the sprawling appropriation generation of the early ’80s that included artists like Barbara Kruger, Cindy Sherman and Jeff Koons and that continues to add new recruits, like Wade Guyton and Kelley Walker.

In a sense his career has been a process of self-liberation by expanding upon an esoteric mode that he helped invent. His early work, the essence of orthodox postmodern appropriation, consists of influential yet hermetic rephotographs of the ads and fashion spreads in glossy magazines. Cropped, enlarged and grouped according to subject and pose, these images exposed with almost anthropological precision advertising’s subliminal codes and stereotypes. For all its elegance, the early work had a spindly endgame air that seemed to disdain anything as touch-feely as making an actual art object. But that is just what Mr. Prince proceeded to do, regularly introducing new subjects, mediums and techniques.

The primness of the early photographs gives way to the Technicolor flamboyance of the Cowboy series, pirated from the famous Marlboro Country campaign. Then come the grainy, clustered “gangs,” as he called them, of related magazine images — big-wheeled trucks, rock bands, surfers’ waves. Surprisingly, Mr. Prince’s latest camera works reject appropriation altogether. They are dour yet lyrical images of the hardscrabble area in upstate New York where he lives.

His paintings have become similarly free, or perhaps traditional, as evinced by his pulp-fiction-cover Nurse series. But the final gallery leaves him working at new extremes. On the one hand he seems to be painting for all his worth in his garish new reprises of de Kooning’s “Women,” in which most of the girls are guys who look a little too much like Jar Jar Binks. On the other are his latest straight-out ready-mades: the American English series simply and suavely juxtaposes American and English editions of books like Lenny Bruce’s “How to Talk Dirty and Influence People” or Bob Dylan’s “Tarantula,” creating a subtle exegesis of the national character of design.

Early in the show an especially imposing joke painting offers a summation of his ambition. “I Know a Guy” (2000) has a snowy surface powdered with eminently touchy-feely plumes of pastel but starkly divided by a horizontal band of large black Helvetica type, all caps and hand-stenciled. In a crowded rush, the words inject a twitching dose of stand-up monologue: “I knew a guy who was so rich he could ski uphill. Another one, I told my mother-in-law my house is your house. Last week she sold it. Another one … ”

The clincher here is the urgent aside “another one,” which has echoes in subsequent joke paintings: “Again.” “One more.” It turns these paintings into portraits of the artist at work, sweating it out, honing his material and timing, egging himself on to come up with another one and then another one until he gets our full attention, cracks us up and, in stand-up parlance, kills.

That, in a nutshell, might be the story of Mr. Prince’s career, one of nonstop production, of collecting, editing and honing, of sifting and shifting styles and techniques, and getting better all the time. Among other things, it means that the Nurse and the de Kooning series, if continued, can only improve.” – Roberta Smith