Ian Aleksander Adams

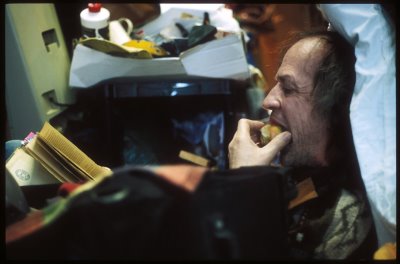

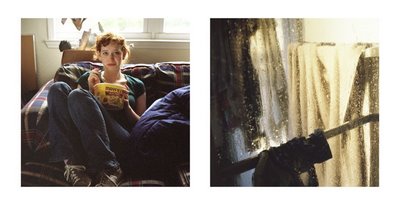

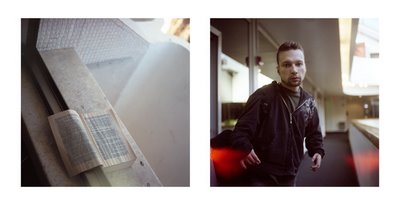

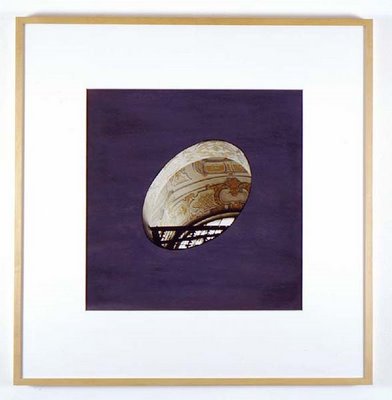

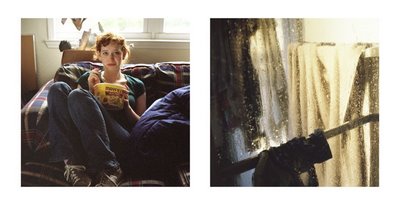

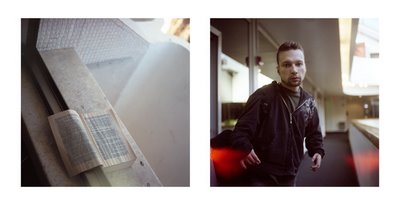

Work from Gray Days.

The following is an email dialouge that Ian and I had yesterday that discusses his work. It really was a treat to have an intelligent Trans-Atlantic back and forth about art.

Ian: Gray Days is my most recent book project, with the final touches still being put on it. Being Inside was the first attempt to pull something together from my personal work, and ended up being much more conceptually specific. Israel By Land was also shot during the Gray Days period, and there is some crossover.

So I don’t have a final statement that I’d want to send just yet, but I’m more than happy to talk a little bit about it.

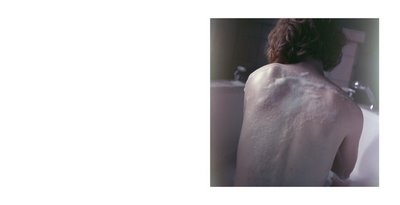

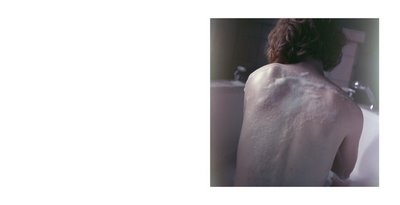

The book, which is small and personal (7 inches, the blurb square, is perfect for it, I think), is either a culmination or a significant step in about 4 years of shooting. The creative process for this book centers on the editing and discovery of visual sensibility, instead of being founded on a specific subject based project mentality. Basically, I wanted to look at what I’d been taking pictures of and let myself make connections in a more organic matter in order to learn more about what I took with myself when I was shooting. So it’s a book about New England, with many of the pictures taken very far from the area I was raised. It’s a book about Gray Days, but not about gray days. It’s a book about fuzziness and poetic sequence, about in betweens instead of solid blacks or pristine whites.

It’s very mundane, but it’s not, I hope.

I hope some of that helps. It’s a body of work that I think speaks for itself in many ways – on most levels, it is what it is. But I don’t want it to sound simple. It took many months of just editing and moving pictures around till I felt it was perfect, as well as the creative input of many minds. From the get-go, though, I was hoping to make a project that resisted the quick and dirty artist statement approach to creating work, and that makes it more difficult to describe verbally.

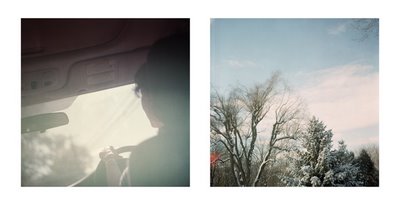

Jordan: There were a few things that specifically drew me to the work, and I was wondering if maybe I could ask some vague questions that could get us somewhere productive. One of the aspects that drew me into the work was the film-specific aesthetic, not in the use of grain or color palate or any sort of preferential film v. digital usage, but in the inherent acknowledgement of photographic process evident in processing marks, chemical stains, and light leaks. Quite possibly, I am sensitive to this sort of treatment because of a strong conceptual interest in medium-specific contexts and self-reflexive works, but regardless, it brought me in.

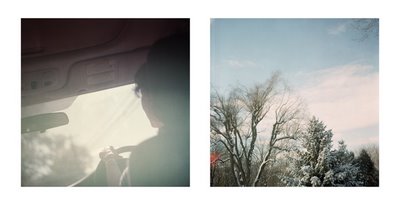

In some ways this is what interests me about contemporary Dutch photography, but their aesthetic sometimes balks at formal composition or thematic cohesion in a way that I find less appealing than your work. It was also the use of diptych that I found interesting, with some images paired and some left alone, yet still organized in book form. Were the pairings mostly formal, organic, trail and error type of diptychs (I view them this way rather than recto-verso) until something felt right, or was there any sort of conceptual narrative to how the book is structured?

Ian: I’ve been very interested in the physical manifestations of photographic process – though perhaps more in a metaphorical or purely aesthetic sense, instead of a technical one. They tend to represent a shift in how I felt about photographing in general – embracing of fear, acceptance of failure, perhaps – and I’ve written a fair amount along those lines. Maybe you saw the article published in ahorn magazine? Here’s the link: (On Fear And Photography)

While an art student, I had many debates with my teachers about the “right” and “wrong” of creating images. Phrases like “underexposed” irked me, because of their inference of a “proper” exposure. To me, the “correct” exposure would always be the version of the image that had the emotional impact that reached me the most. Often times that would be the image at the end of the roll, or the one with the light leaks, or the one four stops underexposed. When I showed these to teachers out of context, they were almost always under appreciated, but I think after several months editing, they were allowed to be what they were.

It’s like the crooked skylines of that one landscape photographer – one crooked skyline was a mistake, but in context, they were a vision, a way of looking at the world. Learning to let these things be as they should, instead of “correcting” them in some manner is just as hard as learning the “rules” for successfully pleasing an advertising director, haha. It takes willpower to just let them sit until they become comfortable – often the impulse to change them is only within myself, not something wrong with the picture.

And since I was learning to embrace a more risky style of shooting (vintage camera, expired film, neglected light meter), I would often be reacting to the final images themselves, not trying to create what I thought might be the best way to capture something – if that makes any sense. Many of these images were taken, scanned, and then left alone for several years before becoming part of the editing process for the book. When I saw them again, it was as if I was discovering them for the first time, and their existence was purely as photographic object, as image, and not as representational of something that had happened. Obviously that’s only one layer of their existence, but that was the most important one to me for much of the editing process. I wanted to see what they did as images.

Of course, at the same time, it’s almost impossible to think of a picture of something as just the picture – the “something” matters very much. I think that for much of the small books, though, I was photographing feelings, mindsets… moods, not objects. Perhaps you can see that? It tends to come across more in book and series form, it’s an aspect to the work often lost in individual prints, one of the reasons I don’t often focus on selling prints as the primary art object.

So the pairings and sequence, they might be the real crux of the art here. I think a lot of the individual images are beautiful, some may even be excellent pictures, but real poignancy doesn’t seep into the work until it is appreciated together. I spent a long time making sure each page turn worked in some fashion, each image was working on the page with others. I wasn’t satisfied with what an image did to the viewer, I wanted to see what the images would do to other images.

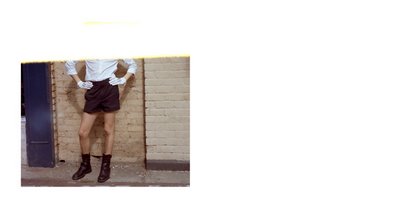

I also spent a lot of time making decisions about the overall sequence. Subject matter, and even exact subjects, are revisited throughout the book. Time is played with. I didn’t want it to be direct and easy, it had to stay gray in all aspects, so time flows in strange ways. Also, as a direct reaction to seeing people flip through my other books, the book ends and begins with the same subject. Many industry professionals will flip through a book from end to beginning, and I wanted that to still be a moving experience.

People know that a lot of editing goes into books, but they often focus on selecting the “best” or “strongest” images. That was not my intention. You don’t make a song by only including the loudest sounds, you don’t make a poem by only including the harshest words. In order for something to flow, it needs to have rhythm, it needs to have waves. So I included images where they felt right, without worrying too much about their individual strength. It makes sense for the viewer to spend less time on some pages than others. If every image is an explosion, the viewer feels worn out, tired. I know there are not many explosions, in this book, it’s not that kind of work, but I think you understand what I mean.

In the same way, not every spread is a diptych. There are no rules for this kind of work, and getting stuck in a pattern is often detrimental. I included that half frame image of the young man in the mickey mouse costume, and I included it on the left hand side for this very reason. It’s designed to let the viewer know that this book is not just a set of pictures, it’s a poem that is in an order, and may catch you off guard or pass you by if you are not paying attention.