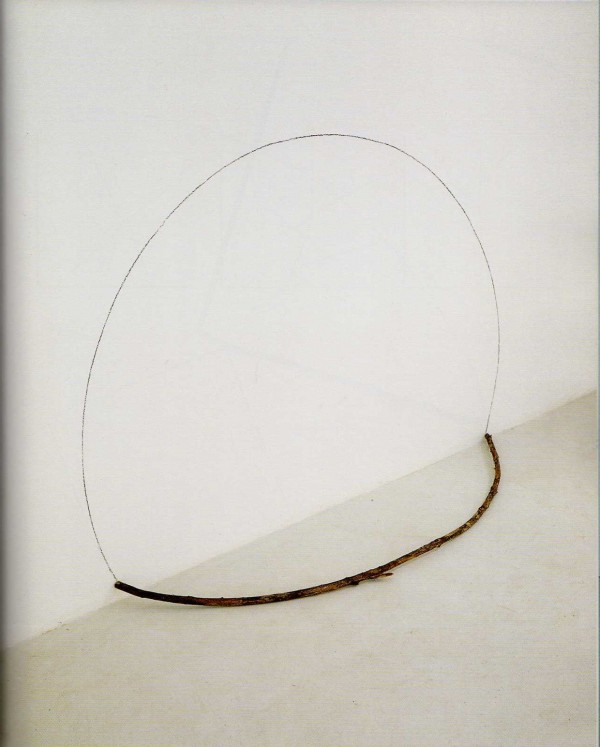

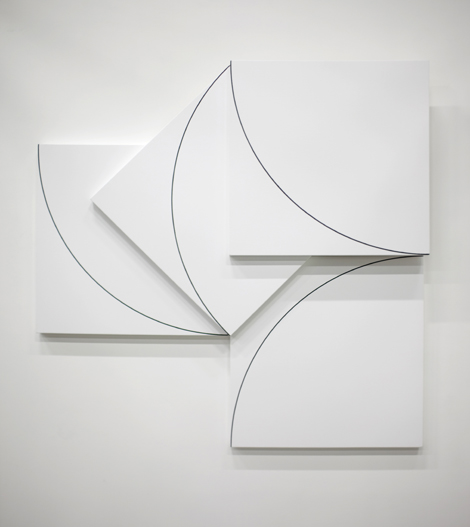

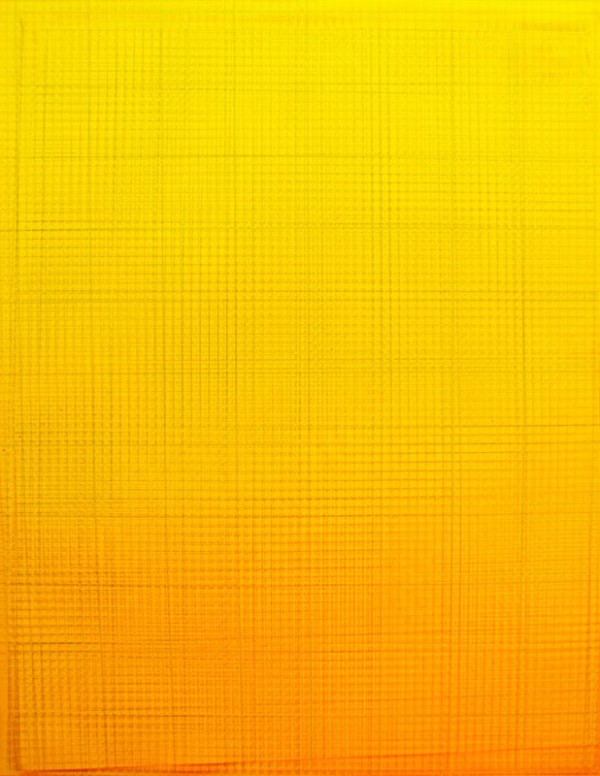

Isabelle Cornaro

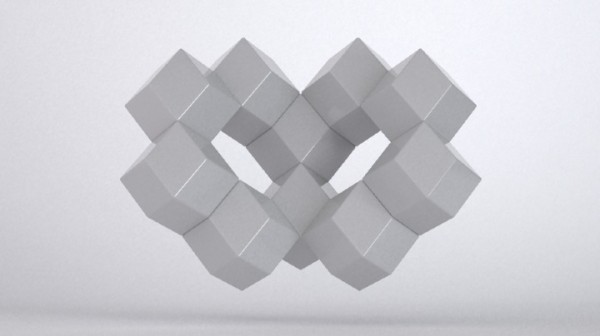

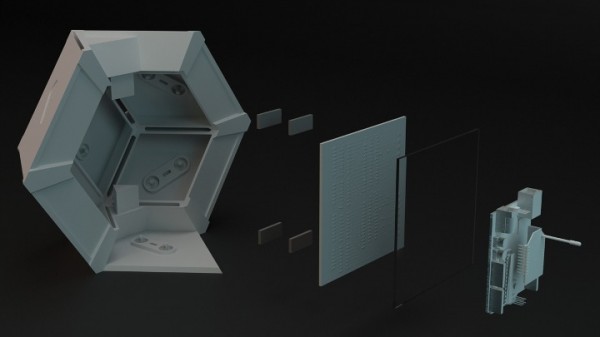

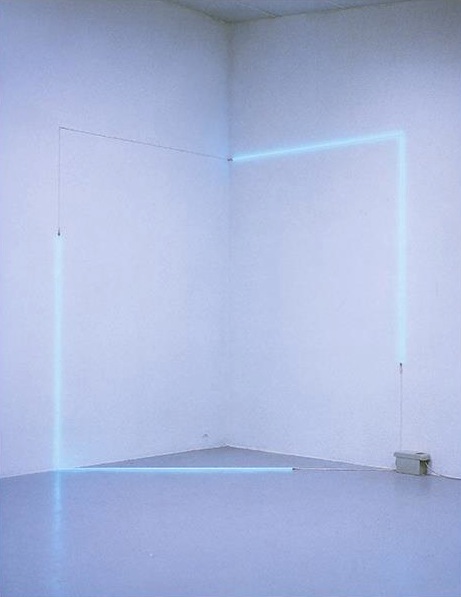

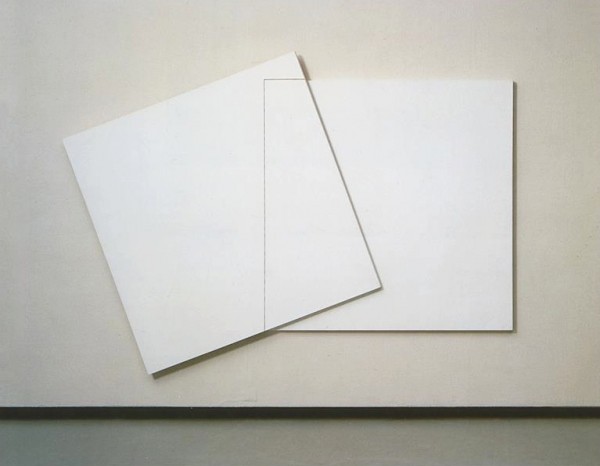

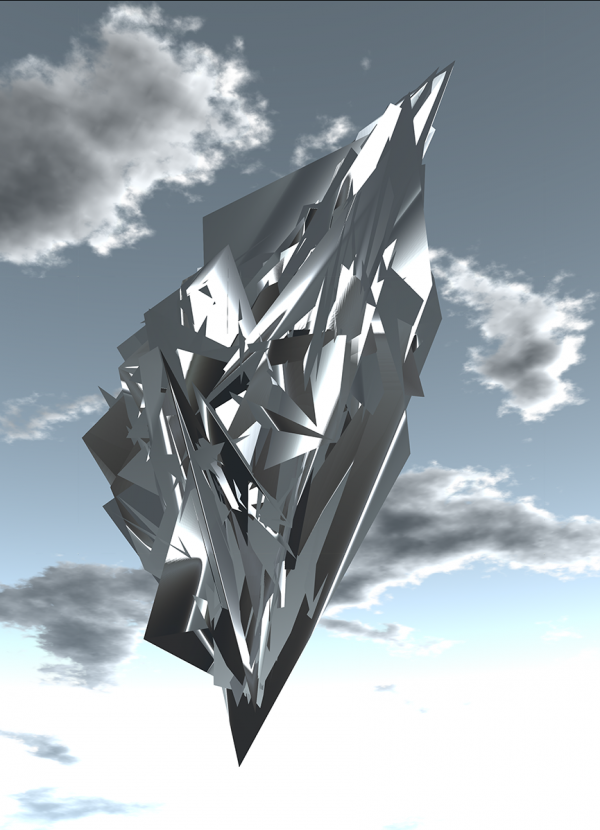

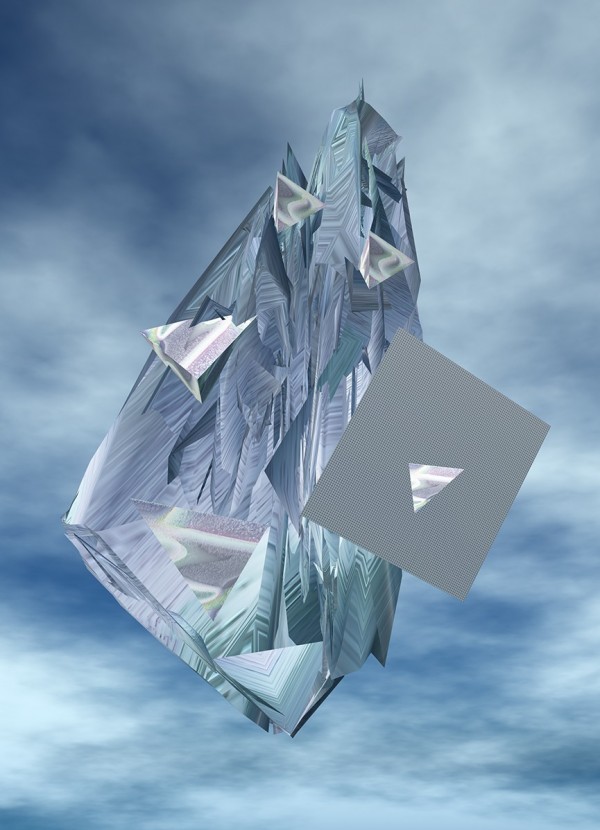

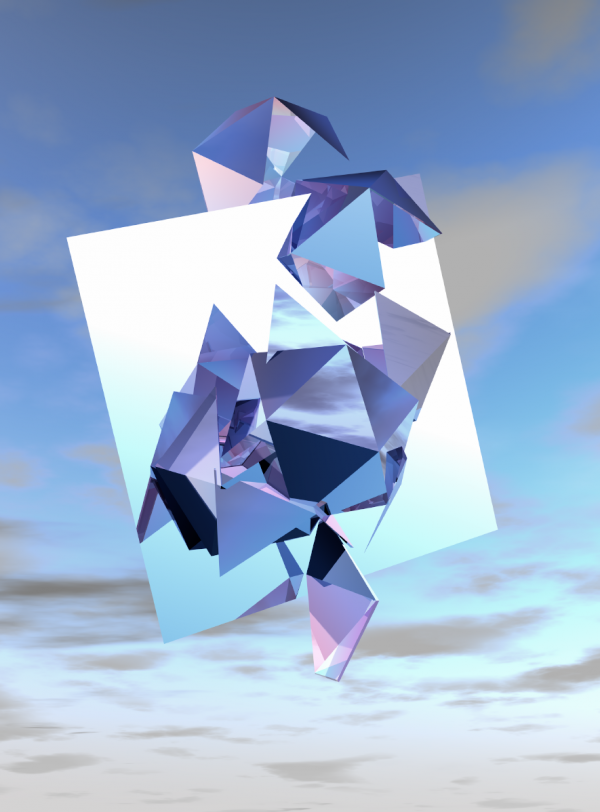

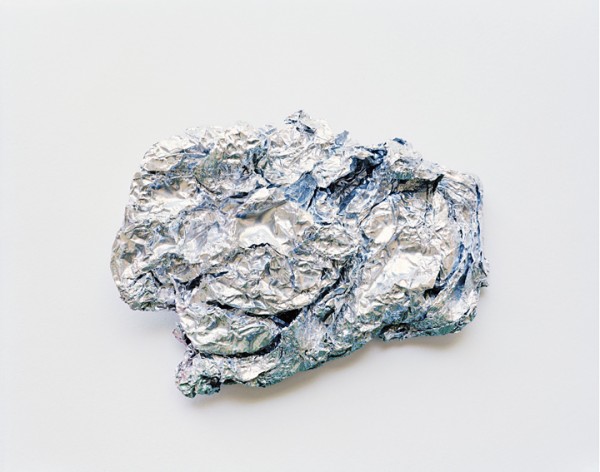

Work from her exhibition at Kunsthalle Bern.

“Six questions to Isabelle Cornaro on the occasion of her exhibition

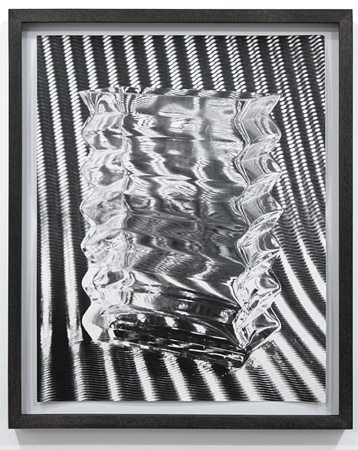

Fabrice Stroun: At Kunsthalle Bern, you will exhibit two sets of cast works, one horizontal the other vertical, which are collectively titled Homonymes. Most of the objects you are using to make these casts seem to come from a defunct era; old-fashioned tchotchkes found in someone’s attic or at the flea market.

Isabelle Cornaro: They do indeed come from flea markets, which I visit without any pleasure. I dislike the slightly pornographic relationship to objects, half-sentimental, half-lecherous, that these kinds of places generate. The objects I select are domestic, decorative baubles (vases with ‘Oriental’ motifs, cheap glassware, Christmas decorations, etc.), outdated tools (rubber stamps, metronomes, old camera lenses, etc.), my own worn-out working tools (small varnished plinths, bits of bubble wrap, plaster, glass sheets, slides, etc.) as well as objects linked to money (coins, bills, poker chips, piggy banks, etc.) or to pageantry (perfume bottles, jewels, medals, lipsticks, etc.). There are rarely any direct human representations, only abstract, vegetable, animal and mineral motifs. All these objects are the product of semi-industrial labor (since none or very few of them are actually hand-made) and they articulate the values of a social class– which happens to be, most of the time, my own.

FS: Is this a way of bringing to the fore an autobiographical dimension in your work?

IC: No, not in this sense. It’s just that, having grown up with them, these objects are familiar. I know them intimately. The very first objects I ever used to make art are jewels that belonged to my mother. Not only did I have them at my fingertips, but I had also seen them in old photographs that date to a time when my parents were living in a former French colony. The jewels were made with local gold and diamonds, the very natural resources that got the French there in the first place. Today, the majority of the objects I work with would be copies of copies of precisely such jewels: surrogates.

FS: The use of this ideologically charged, depleted decorative aesthetic demarcates a semantic field that is very much your own. Your work seems relatively impervious to avant-garde citations or to the globalised pop culture so many of your contemporaries draw on.

IC: I find it difficult to work with pop culture because, in my opinion, it is already overflowing with meaning. Most importantly, pop tends to generate a positive, sentimental relationship to culture that I find unproductive. I prefer working with objects that make me ill at ease. This unsympathetic relationship to my source material creates a tension that I much prefer.

FS: Do you consider these casts as ‘models’ of something, or some process, or should we regard them more as ‘allegories’? And if so, allegories of what?

IC: I like the trope of an allegory since it describes an abstract relationship to the world and often calls for the use of figures. The cast object relates to two distinct fields of likeness: to the real objects that were used to make the casts, and to the abstract categories they represent.

FS. Are you talking about aesthetic categories of representation or art-historical ones, which relate more to technique?

IC: The categories I refer to are empirically defined, most often while observing different objects lying around my studio at a given time. For the horizontal Homonymes, for example, I identified three distinct families of objects: naturalistic objects (even when streamlined), ‘in the shape of’ a duck, a flower; etc., objects carved with decorative motifs, repeated and stylized, and objects sporting geometrical form– even if impure– that brought to mind a notion of abstraction. In other words, my categories were Naturalism, Stylization and Abstraction. A fourth cast was then made with all the ‘leftovers’.

FS: Once you have defined an ensemble of objects, what formal or processual principle presides over their assembly?

IC: It really depends on the series I am working on. As far as the Homonymes are concerned, they are not so much composed as simply piled up. The absence of composition allows me to put aside my subjectivity, or at least my ‘sensibility’. This allows me to move from formal (or stylistic) to more categorical considerations. Here, the piles were thought of as ‘heaps’, following a functional rather than an aesthetic logic. By that I mean that spacing had to be sufficient for the technician to make the casts, with various heights so as to reveal the maximum detail, etc. One thing that really matters to me is that the cast is molded in a single take. It is a solidifying, a change of material state– meaning that all the objects used become a single mass; ‘drawn’ shapes, emerging from a formless block of matter. An important point of reference for me are 16th-century Mannerist grottos, where animals and flowers are sculpted in a mass that remains partly formless, or, rather, keeps its initial natural shapes. There are also other grottos where the entire stone is sculpted, including the parts that are supposed to be formless; ‘natural’ matter. The material and the manner in which it is used projects an image of reification, i.e. of death – the passage from a living, animated body to that of an object, that is to say, of a corpse.

Isabelle Cornaro was born 1974 in France. She lives and works in Paris. Major presentations of her work were organized by the Kunstverein Düsseldorf (2009) and Le Magasin (2012) in Grenoble. Kunsthalle Bern presents her first monographic exhibition in Switzerland. The exhibited works date from 2006, such as All we ever see of stars, to this day. Two new large productions, Celebration and God Box No. 1-3, were made specifically for this exhibition.” – Kunsthalle Bern

via Contemporary Art Daily