Matten Vogel

Work from Zensiert (Censored).

The diptychs are my doing for formatting reasons.

“Censorship is the reverse of liberty. It means repression. Involves the suppression of all form of self-determined thoughts and comments by controlling authorities that are higher placed in the hierarchy. It can be instituted by the government or – you only have to think of Michelangelo’s frescos in the Sixtine Chapel – the church. But it also originates from superiors, parents and teacher, that say boycott the establishment of a works council, forbid their children to wear outlandish clothes, and is equally in the decision not to print the critical contribution to the school magazine. In other words, censorship can extend to everyday things – and at times there is no clear-cut dividing line between it and what is generally referred to as “education”.

Yet censorship need not necessarily have a negative touch. Given the unabated flood of information produced by the Internet for instance, it can become a real necessity. And who is to decide where legal protection for young people begins, and the obstruction of liberal expression begins? Essentially, censorship is nothing more than an expression of people’s longing to get a grip on life. It represents the desire to uphold existing orders by controlling and limiting whatever goes beyond the familiar, challenges it, or otherwise threatens its existence. At any rate, in the generally accepted sense censorship is more an enemy of art, and by no means its ally.

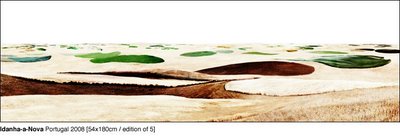

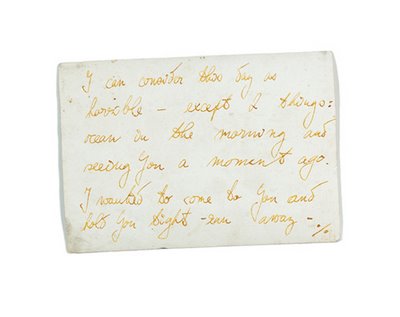

Matten Vogel is aware of this. But it does not seem to bother him. On the contrary. He deliberately incorporates the censorship principle into his artistic work. His method: he takes photos from magazines, books or brochures, selects a section, which he then scans, and places censorship strips across it. Sometimes the black strips are large, sometimes small, at times they appear in isolation, at others several occur together. They are placed across the faces of individuals or a group of relaxed-looking people in summer clothes, eagerly taking photos. But they occur equally in photos of buildings destroyed by natural catastrophes or in idyllic scenes of mountains, forests or seascapes. The important aspect for Vogel in making his selection is that the subjects are not generally known, and as such occupy no place in the observer’s collective memory. For all that, they do not deny their origin, and are easily recognizable in their aesthetic as newspaper, advertising or fashion photographs.

Evidently, there are no natural subject-related laws governing the positioning of the censorship strips. If the photos include persons, they are placed over the eyes in the manner familiar to us from pictures observing data protection and privacy laws. This approach seems to make sense in individual portraits, but the situation becomes difficult to decipher when a crowd of people is depicted. In such cases, it is no longer possible to grasp the selection criteria the artist applies to determine which faces to cover, and which to leave uncovered. The whole thing becomes more puzzling still when the black strip floats unencumbered above forest clearings, in snow-covered mountain valleys, or a blue expanse of sky. Is it really concealing something, thereby having a proven subject-related function? Or is it not more the case that it has a formal purpose, is designed to lend the existing picture rhythm and restructure it? Censorship as a means of creating a picture? To Matten Vogel’s way of thinking this is not a contradiction.

That much is evident when he say places the strip on the horizon of a (North German?) landscape exactly in relation to the golden section. And it is also apparent in the two levels that are unified in every photograph. Firstly, there is the original photo which has been visibly scanned. Across the latter’s bepixeled surface Vogel places the pin-sharp strip, which though it varies in size always forms the picture’s dominant element. This effectively defines the original picture’s content level through the artistic element of the censorship strip. The overlapping of both areas becomes particularly obvious through Vogel’s employment of the classic, black censorship strip which assumes a truly old-fashioned appearance. Today, people tend to rely on soft-focus lenses or superimpose patterns over the bare breasts of dancing beauties on MTV videos. But such censorship would detract from the formal aspect of fuzziness already expressed in the scanned originals, and would reinforce rather than counteract it. Moreover, the artist believes such methods have a minimizing effect: “whereas censorship strips may be brutal, but are honest.”

Already in Matten Vogel’s earlier works we can detect him resorting to control devices, such as the censorship principle in this series. In the video installation “Private” from the year 2001, for instance, he presents night shots of apartment windows on four monitors, whose blurriness evokes the surveillance images familiar to us from popular spy movies. Not that much happens. Occasionally a curtain moves here, a shadow flits behind the drawn curtain, elsewhere the TV screen flickers – unspectacular images reproduced for no immediately apparent reason, that nonetheless expose the private sphere of strangers. Though the monitors reveal a lack of activity, the observer is however a willing party to it. After all, nobody has granted them permission to see what they do, and the participants are not aware they are party to them. This knowledge can produce a vague sense of one’s own superiority, one’s own power.

A sense shared by Vogel perhaps vis-à-vis these censored pictures. Ultimately, we are not confronted with censorship by a third party, but by the artist himself, as he never tires of emphasizing in the epithet “censored by Matten Vogel”, that accompanies every single work in the 18-part series. This effectively lends the paradox nature of his action an almost grotesque quality: The artist as the highest control authority of his own work, and in this function simultaneously a creator of something new. The desire to submit to such fantasies of omnipotence certainly occurs repeatedly in his work. And why not?

This is precisely the fascination that drives Matten Vogel. The idea of not only being a creator of new visual worlds as an artist but of also going further. And furthermore to do so by resorting to things such as surveillance or censorship, to elements that are seemingly diametrically opposed to the creative process, indeed normally obstruct it. Vogel employs them consciously with deliberate clarity, and with their assistance creates something new from what exists – according to his concepts. In the process, what once existed in the first photo loses its original message, is treated like a sketch precursory to the actual work, becomes equally a means to an end as does the positioning of the black strip on it. Censorship is not understood here as restriction but rather as a vehicle of expansion, an expression of artistic liberty. Or better still: The image of censorship omnipotence is transformed into a synonym for the artist’s power in an open, creative process. The artist as a censor for the sake of the picture – for Matten Vogel the two are by no means mutually exclusive.” – Janneke de Vries