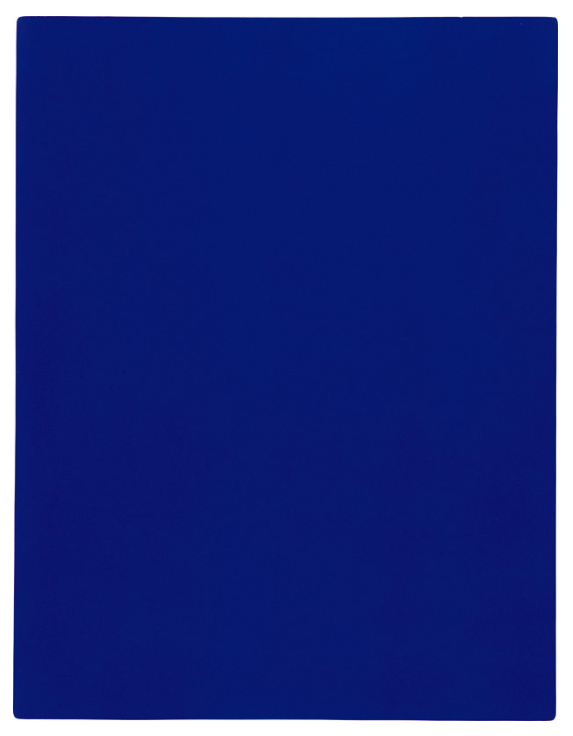

Work from his oeuvre.

“Due to the fact that I have painted monochromes for fifteen years,

Due to the fact that I have created pictorial immaterial states,

Due to the fact that I have manipulated the forces of the void,

Due to the fact that I have sculpted with fire and with water and have painted with fire and with water,

Due to the fact that I have painted with living brushes — in other words, the nude body of live models covered with paint: these living brushes were under the constant direction of my commands, such as “a little to the right; over to the left now; to the right again, etc.” By maintaining myself at a specific and obligatory distance from the surface to be painted, I am able to resolve the problem of detachment.

Due to the fact that I have invented the architecture and the urbanism of air — of course, this new conception transcends the traditional meaning of the terms “architecture and urbanism” — my goal from the beginning was to reunite with the legend of Paradise Lost. This project was directed toward the habitable surface of the Earth by the climatization of the great geographical expanses through an absolute control over the thermal and atmospheric situation in their relation to our morphological and psychical conditions.

Due to the fact that I have proposed a new conception of music with my “monotone-silence-symphony,”

Due to the fact that I have presented a theater of the void, among countless other adventures…

I would never have believed, fifteen years ago at the time of my earliest efforts, that I would suddenly feel the need to explain myself — to satisfy the desire to know the reason of all that has occurred and the even still more dangerous effect, in other words — the influence my art has had on the young generation of artists throughout the world today.

It dismays me to hear that a certain number of them think that I represent a danger to the future of art — that I am one of those disastrous and noxious results of our time that must be crushed and destroyed before the propagation of my evil completely takes over.

I regret to reveal that this was not my intention; and to happily proclaim to those who evince faith in the multiplicity of new possibilities in the path that I prescribe — Take care! Nothing has crystallized as yet; nor can I say what will happen after this. I can only say that today I am no longer as afraid as I was yesterday in the face of the souvenir of the future.

An artist always feels uneasy when called upon to speak of this own work. It should speak for itself, particularly when it is valid.

What can I do? Stop now?

No, what I call “the indefinable pictorial sensibility” absolutely escapes this very personal solution.

So…

I think of those words I was once inspired to write. “Would not the future artist be he who expressed through an eternal silence an immense painting possessing no dimension?”

Gallery-goers, like any other public, would carry this immense painting in their memory (a remembrance which does not derive at all from the past, but is solely cognizant of the indefinable sensibility of man).

It is necessary to create and recreate a constant physical fluidity in order to receive the grace which allows a positive creativity of the void.

Just as I created a “monotone-silence-symphony” in 1947, composed in two parts, — one broad continuous sound followed by an equally broad and extended silence, endowed with a limitless dimension — in the same way, I attempt to set before you a written painting of the short history of my art, followed naturally by a pure and affective silence.

My account will close with the creation of a compelling a posteriori silence whose existence in our communal space, after all — the space of a single being — is immune to the destructive qualities of physical noise.

Much depends upon the success of my written painting in its initial technical and audible phase. Only then will the extraordinary a posteriori silence, in the midst of noise as well as in the cell of physical silence, operate in a new and unique zone of pictorial immaterial sensibility.

Having reached today this point in space and knowledge, I propose to gird my loins, then to draw back in retrospection on the diving board of my evolution. In the manner of an Olympic diver, in the most classic technique of the sport, I must prepare for my leap into the future of today by prudently moving backward, without ever losing sight of the edge, today consciously attained — the immaterialization of art.

What is the purpose of this retrospective journey in time?

Simply, I wish to avoid that you or I fall under the power of that phenomenon of dreams, which describes the feelings and landscapes provoked by our brusque landing in the past. This psychological past is precisely the anti-space that I put behind me during the adventures of these past fifteen years.

At present, I am particularly excited by “bad taste.” I have the deep feeling that there exists in the very essence of bad taste a power capable of creating those things situated far beyond what is traditionally termed “The Work of Art.” I wish to play with human feeling, with its “morbidity” in a cold and ferocious manner. Only very recently I have become a sort of gravedigger of art (oddly enough, I am using the very terms of my enemies). Some of my latest works have been coffins and tombs. During the same time I succeeded in painting with fire, using particularly powerful and searing gas flames, some of them measuring three to four meters high. I use these to bathe the surface of the painting in such a way that it registered the spontaneous trace of fire.

In sum, my goal is twofold: first of all, to register the trace of human sentimentality in present-day civilization; and then, to register the trace of fire, which has engendered this very same civilization — that of the fire itself. And all of this because the void has always been my constant preoccupation; and I believe that fires burn in the heart of the void as well as in the heart of man.

All facts that are contradictory are authentic principles of an explanation of the universe. Truly, fire is one of these principles, essentially contradictory, one from the other, since it is both the sweetness and torture that lies at the heart and origin of our civilization. But what stirs this search for feeling in me through the making of super-graves and super-coffins? What stirs this search in me for the imprint of fire? Why search for the Trace itself?

Because every work of creation, regardless of its cosmic place, is the representation of a pure phenomenology — all that is phenomena manifests itself. This manifestation is always distinct from form and it is the essence of the Immediate, the Trace of the Immediate.

A few months ago, for example, I felt the urge to register the signs of atmospheric behavior by recording the instantaneous traces of spring showers on a canvas, of south winds, and of lightning (needless to say, the last-mentioned ended in a catastrophe). For instance, a trip from Paris to Nice might have been a waste of time had I not spent it profitably by recording the wind. I placed a canvas, freshly coated with paint, on the roof of my white Citroën. As I drove down Route Nationale 7 at 100 kilometers an hour, the heat, the cold, the light, the wind, and the rain all combined to age my canvas prematurely; At least thirty to forty years were condensed into a single day. The only annoying thing about this project is that for the entire trip I was unable to separate myself from my painting.

My atmospheric imprints of a few months ago were preceded by vegetal imprints. After all, my aim is to extract and obtain the trace of the immediate from all natural objects, whatever their origin — be the circumstance human, animal, vegetable, or atmospheric.

I would like now, with your permission and close attention, to divulge to you possibly the most important and certainly the most secret phase of my art. I do not know if you are going to believe me — it is cannibalism. After all, is it not preferable to be eaten than to be bombed to death? I can hardly develop this idea that has tormented me for years. I leave it up to you to draw your own conclusions with regard to the future of art.

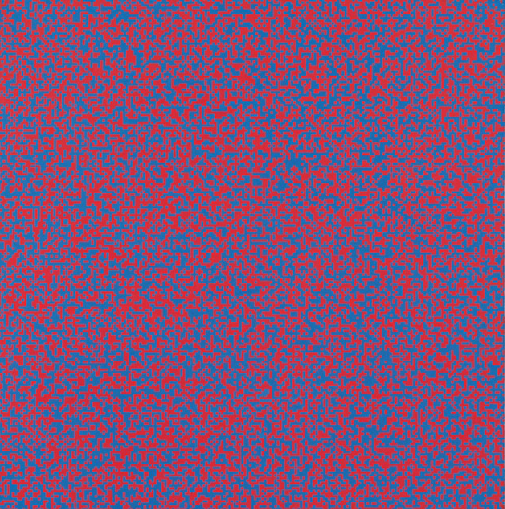

If we step back again, following the lines of my evolution, we arrive at the moment when I conceived of painting with the aid of living brushes. That was two years ago. The purpose of this was to be able to attain a defined and constant distance between myself and the painting during the time of creation.

Many critics claimed that by this method of painting I was doing nothing more than recreating the method that has been called “action painting.” But now, I would like to make it clear that this endeavor is distinct from “action painting” in so far as I am completely detached from all physical work during the time of creation.

Just to cite one example of the anthropometric errors found within the deformed ideas spread by the international press — I speak of that group of Japanese painters who with great refinement used my method in a strange way. In fact, these painters actually transformed themselves into living brushes. By diving themselves in color and then rolling on their canvases, they became representative of ultra-action-painters! Personally, I would never attempt to smear paint over my body and thus to become a living brush; to the contrary, I would rather put on my tuxedo and don white gloves.

It would never cross my mind to soil my hands with paint. Detached and distant, the work of art must be completed under my eyes and under my command. As the work begins its completion, I stand there — present at the ceremony, immaculate, calm, relaxed, perfectly aware of what is taking place and ready to receive the art being born into the tangible world.

What directed me towards anthropometry? The answer can be found in the work that I made during the years 1956 to 1957 while I took part in that giant adventure, the creation of pictorial immaterial sensibility.

I had just removed from my studio all earlier works. The result — an empty studio. All that I could physically do was to remain in my empty studio and the pictorial immaterial states of creation marvelously unfolded. However, little by little, I became mistrustful of myself, but never of the immaterial. From that moment, following the example of all painters, I hired models. But unlike the others, I merely wanted to work in their company rather than have them pose for me. I had been spending too much time alone in the empty studio; I no longer wanted to remain alone with the marvelous blue void which was in the process of opening.

Though seemingly strange, remember that I was perfectly aware of the fact that I experienced none of that vertigo, felt by all my predecessors, when they found themselves face to face with the absolute void that is, quite naturally, true pictorial space.

But how long could my security in this awareness endure?

Years ago, the artist went directly to his subject, worked outdoors in the country, had his feet firmly planted on the ground — it was healthy.

Today, easel-painters have become academics and have reached the point of shutting themselves in their studios in order to confront the terrifying mirrors of their canvases. Now the reason I was pushed to use nude models is all but evident: it was a way of preventing the danger of secluding myself in the overly spiritual spheres of creation, thus breaking with the most basic common sense repeatedly affirmed by our incarnate condition.

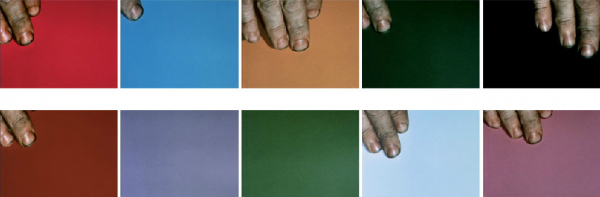

The shape of the body, its lines, its strange colors hovering between life and death, hold no interest for me. Only the essential, pure affective climate of the flesh is valid.

Having rejected nothingness, I discovered the void. The meaning of the immaterial pictorial zones, extracted from the depth of the void which by that time was of a very material order. Finding it unacceptable to sell these immaterial zones for money, I insisted in exchange for the highest quality of the immaterial, the highest quality of material payment — a bar of pure gold. Incredible as it may seem, I have actually sold a number of these pictorial immaterial states.

So much could be said about my adventure in the immaterial and the void that the result would be an overly extended pause while steeped in the present elaboration of a written painting.

Painting no longer appeared to me to be functionally related to the gaze, since during the blue monochrome period of 1957 I became aware of what I called the pictorial sensibility. This pictorial sensibility exists beyond our being and yet belongs in our sphere. We hold no right of possession over life itself. It is only by the intermediary of our taking possession of sensibility that we are able to purchase life. Sensibility enables us to pursue life to the level of its base material manifestations, in the exchange and barter that are the universe of space, the immense totality of nature.

Imagination is the vehicle of sensibility!

Transported by (effective) imagination we attain life, that very life which is absolute art itself.

Absolute art, what mortal men call with a sensation of vertigo the summum of art, materializes instantaneously. It makes its appearance in the tangible world, even as I remain at a geometrically fixed point, in the wake of extraordinary volumetric displacements with a static and vertiginous speed.

The explanation of the conditions that led me to pictorial sensibility is to be found in the intrinsic power of the monochromes of my blue period of 1957. This period of blue monochromes was the fruit of my quest for the indefinable in painting, which Delacroix the master could already intimate in this time.

From 1946 to 1956, my monochrome experiments, tried with various other colors than blue, never allowed me to lose sight of the fundamental truth of our time — namely that form, henceforth, would no longer be a simple linear value, but rather a value of impregnation. Once, in 1946, while still an adolescent, I was to sign my name on the other side of the sky during a fantastic “realistico-imaginary” journey. That day, as I lay stretched upon the beach of Nice, I began to feel hatred for birds which flew back and forth across my blue sky, cloudless sky, because they tried to bore holes in my greatest and most beautiful work.

Birds must be eliminated.

Thus, we humans will have acquired the right to evolve in full liberty without any physical and spiritual constraint.

Neither missiles nor rockets nor sputniks will render man the “conquistador” of space.

Those means derive only from the phantom of today’s scientists who still live in the romantic and sentimental spirit of the XIX century.

Man will only be able to take possession of space through the terrifying forces, the ones imprinted with peace and sensibility. He will be able to conquer space — truly his greatest desire — only after having realized the impregnation of space by his own sensibility. His sensibility can even read into the memory of nature, be it of the past, of the present and of the future!

It is our true extra-dimensional capacity for action!

If proofs, precedents or predecessors are needed, let me then cite Dante, who in the Divine Comedy, described with absolute precision what no traveler of his time could reasonably have discovered, the invisible constellation of the Northern Hemisphere known as the Southern Cross;

Jonathan Swift, in his Voyage to Laputa, gave the distances and periods of rotation of the satellites of Mars though they were unknown at the time;

When the American astronomer, Asoph Hall, discovered them in 1877, he realized his measurements were the same as those of Swift. Seized by panic, he named them Phobos and Deimos, Fear and Terror! With these two words — Fear and Terror — I find myself before you in the year 1946, ready to dive into the void.

Long Live the Immaterial!

And now,

Thank you for your kind attention.” – Yves Klein, Hotel Chelsea, New York, 1961