Florian Slotawa

Work from Hotelarbeiten and others.

“A nondescript zone lies close to the start of Kurfürstenstraße. This should be the core of the city. Neither entirely residential nor commercial nor administrative, this curiously neglected quarter of central Berlin exudes a sense of fun’s absence. It’s where Florian Slotawa likes to work. His new studio is a former office divided into four rooms. The aging carpets and functionally compartmental spaces bear traces of a vanished world of small business bureaucracy circa 1979, lending the new tenancy the air of a squat—which seems entirely appropriate given the nature of Slotawa’s work.

Table and chairs are arranged with formal symmetry in the central room. They could be a work in progress—regress?—or just a place to eat. Turns out it’s the latter. This is one of the effects of Slotawa’s work: you start to notice structures in incidental clusters of things, be they arbitrary accumulations or functional arrangements.

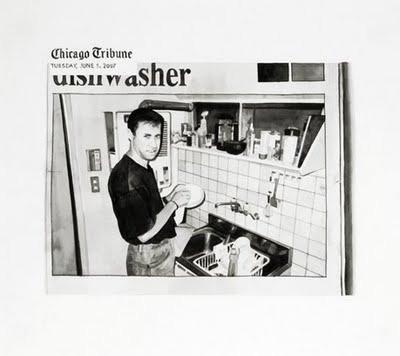

In a corner of an adjoining room, a crate of framed photographs has been recently returned. The series Hotelarbeiten [Hotel Works], 1998-1999, brought Slotawa’s work to the attention of a broad audience. Over the course of a night spent in a hotel, the artist would dismantle the furnishings and fittings of his room and re-assemble them into something between a makeshift shelter and a child’s fantasy hideaway. His journey entailed stopovers in Switzerland, Italy, France, and Germany, resulting in a series of black-and-white photographs of these one-night affairs, which were published in the magazine of the Süddeutsche Zeitung newspaper. And so, the work of Slotawa, who was then still a student, reached an audience well beyond the precincts of the artworld. The public resonance of these images—both quantitative and qualitative—lends them a certain archetypal status in his practice. They are evocative in many ways. While he literally dismantled and abused the hotel rooms, his transgression of the guest-hotelier contract was a matter of the spirit rather than the letter of the law: has any draft of the hotel’s regulations, however pernickety, foreseen this type of behavior? And besides, at the end of his clandestine operation, Slotawa scrupulously returned each room to its prior condition.

Here, the photograph is both an artwork and a document, that is, both a primary and a secondary work: it is both a framed, tonally nuanced picture and simultaneously a document, a piece of evidence that registers an absence, an event that has passed. The event’s clandestine aspect heightens the resonance of the photographs’ evidential nature. They don’t just document a performative intervention, they register a very particular transgression. Imparting knowledge of the transgression makes the audience complicit, however reticently. What’s more, the act’s seeming ineffectuality too has an affective charge. For it seems to rhetoricize its own inconsequentiality: room furnishings are shifted around and then painstakingly put back where they belong—although, of course, the intervention questions where they in fact belong. So, then, has anything happened? Has nothing happened?

Slotawa, the hotel guest, accepts the furnishings and fittings as a kind of inventory, as a given limit, while refusing their configuration. This is a question of dwelling insofar as the remade rooms declare themselves as zones of subjective identification and occupation. They deny the impersonality that’s assumed to be a condition of the hotel room’s function as a hotel room.

What about the specific features of individual re-arrangements? Throughout the hotel works, mattresses with bedding are placed on the floor. Some kind of roof or planar structure—usually a door or similar panel lying on its side—gives shade and shelter. Take Hotel Intercontinental, Zimmer 2116, Leipzig, Nacht zum 12. Dezember 1999, for example. No fasteners are used. Things rest on each other, bearing their loads precariously. The shelters inevitably establish a dialogue with the surrounding furnishings, setting up a kind of formalism-by-default that is constantly deflated by the pragmatic, amateur-engineering logic of their construction.

The Hotelarbeiten rehearses the concerns that have been key to Slotawa’s practice over the last decade: the foregrounding of a movement, often in the form of an exchange between private and public domains, which is intimately connected to the question(ing) of the imperative of display (in art); the insistence on composition; and the temporary nature, that is the moment, of composition. There is remarkable consistency in what—for want of a better word—you could call his method. Its elements are: acceptance and delimitation of a given; intervention upon this given; composition.

The first moment involves a crucial dose of passivity. Something—a situation, an institution, a chair, a night in a room or whatever—is given. An archive of sorts, it is received. It is thrown at the artist; the artist too is thrown into it. In this first moment, the ethic is to accept the condition of passivity, to accept what is given in its totality, and to refuse to select from among its parts. If the artist is to make a move that will allow the work to exceed what is given, it won’t entail editing out elements, preferring some bits while omitting others. As such, this ethic of passivity denies preference——aesthetic or otherwise. Of course, such denial of preference has a familiar historical pedigree. Yet, the originality of Slotawa’s work lies in its surprising attempt to yoke the logics of non-preference and givenness, which a structure like the inventory betokens, to a conception of sculpture as composition.

If the acceptance of what’s given comes first—accomplished perhaps by naming and so delimiting it—the second moment is the structuring of an intervention. Over a number of museum and public institutional exhibitions, Slotawa’s interventions have investigated the boundary between public and private, by way of an exchange between what’s displayed and what’s stored or concealed. In an important early work, Schätze aus zwei Jahrtausenden, 2001, Slotawa displayed all of his personal possessions en masse at the Museum Abteiberg in Mönchengladbach, while he hung works from the museum’s collection in his Berlin apartment. In 2002, as part of his Gesamtbesitz project for Kunsthalle Mannheim, he borrowed pieces from the museum’s ceramic collection to make temporary sculptures by placing them on arrangements of things from the museum’s offices. Also in 2002, he sold his personal possessions to a collector. Four years later, he attempted to reverse the process by borrowing the collector’s personal possessions to use them as materials for the assemblage he contributed to the 2006 Berlin Biennale. But these institutional interventions are not programmatic. For Solothurn, Aussen, 2007, at Kunstverein Solothurn’s Slotawa decided to work exclusively with existing sculptures in an adjacent park. He simply moved all the sculptures together in one spot, creating both a new composition and sites of absence discernible to visitors familiar with the individual sculptures’ usual locations.

In Kieler Sockel, 2004, a series of temporary works at Kunsthalle zu Kiel, he placed figurines from the museum’s historical sculpture collection upon makeshift structures and pseudo-plinths made out of objects from the museum’s offices and shop. As Sabine Rusterholz has observed1, when the museum later bought some of these pieces, it paid for artworks composed of things it already owned. While the Kieler Sockel series is perhaps Slotawa’s most relaxed and playful works, it still features the central polemic of his work: a challenge of the terms of creativity. In a sense, he does not make anything new here.

Nothing is transformed. He only composes—that is, literally, displays together—what already exists. This points to a broader conversation about creativity and the creative behavior of critical art today, when the consumer-citizen-subject faces constant and unrelenting injunctions to be creative. In the early noughties, Sony’s epochal “Go create” tagline was exemplary in this regard, yet only at the more lucid end of a continuum that extended to Canon’s “You Can” and Microsoft’s “Your potential. Our passion.” Such language characterizes a state of affairs beyond the older consumer society, formerly described by the phrase “consumption = production.” The dynamics of cognitive capital now requires the activation of the consumer-citizen as an expressive, creative subject who extends and safeguards niche markets. In this context, Slotawa’s practice deftly picks out a path around the looming double-bind, where, on the one hand, invention is demanded—”Go create”—and therefore impossible because it already serves other interests, and, on the other hand, invention is apparently a requirement of the artwork’s agency.

But composition is not the only operation at play in Slotawa’s work. In Ohne Titel [Untitled], 2007, the imperative of display returns with a vengeance. Here, it is figured by planarity and frontality. He revisits the division between the visible and the invisible yet necessary substructure of the visible with reference to the effects of painting. The work is both insistently flat and deep, compelling the viewer to consider the construction that underlies the planar composition. The oblique view from the side reveals the things whose topsides are frontally visible in the work. The things in question are domestic appliances and furnishings, though in the fiction of the frontal plane they are cast as pictorial inflections.

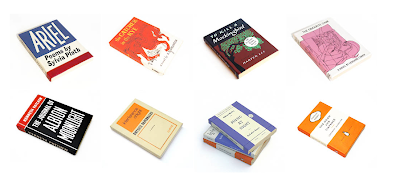

Alongside his interventions occasioned by invitations, Slotawa, who is not yet a post-studio artist, continues a parallel sculptural practice. These self-initiated works, entirely unlinked to an institutional site or frame, have tended to attract fewer words, perhaps because their conceptual narrative is less imposing. And so I will try to redress the balance somewhat. These remarkable pieces extend his working procedure—Slotawa’s method—and enact a mode of sculptural composition, however dysfunctional. From a subjective point of view, Slotawa wants to have stuff to do in the studio, irrespective of which museum phones him next. Small collections of frames removed from a variety of more or less canonical steel frame chairs lean on one of the studio walls. One bundle is from an Eames chair. In Slotawa’s recent works, the chair has become the institution. In a sense the Eames chair is just another institution—another given cultural circumstance, a state of affairs—that will be re-constellated by the work. Again, as in Hotelarbeiten, a certain ethic is in play that shuns fasteners and adhesives. In works such as SG.043.2, 2008, gravity and the chair frame alone must hold in place the steel structure that Slotawa inserts into the dialogue with the chair frame.

I have used the word “composition”—admittedly a loaded one—to describe Slotawa’s method and works. It’s my word, not his. Although Slotawa is an admirably fluent and persuasive talker about his projects, he has little if anything to say about composition. I’m glad he stays silent about it, not because it is ineffable or too banal to mention, but because it is something that he cannot avoid—something seen and found rather than spoken. An aggressive equilibrium holds together recent pieces like GS.002, 2007, or KS.042, 2007, where dumb gravity is aided and abetted by friction. In that sense, these are nearly unauthored compositions, rendered by gravity and awkward balance.

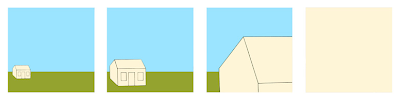

Other works declare that, while composition is the work’s operative condition, it remains radically contingent. In sculpture groups such as SG.02, 2006, Slotawa assembles a small inventory of components in varying configurations. In this serial work, the same parts—folding table, ironing board, and stepladder—are used in four distinct self-supporting arrangements. Composition is here severally contingent: structured first as a side-effect of gravity, and then proposed as a provisional and mutable arrangement. But one thing is crucial: while composition is established as radically contingent or even fully arbitrary, it is not a McGuffin—in Hitchcock’s sense of a plot device that leads the audience by the nose but turns out to be vacuous or irrelevant. In other words, it’s not an instrument of some further target of the work. Theorist Quentin Meillassoux has recently argued for an ontology that not only radically affirms the contingency of the world and its constituent multiplicities, but also finds it to be necessary.2 Meillassoux develops the surprising paradox that contingency itself is not ontologically contingent, but necessary. In other words, the claim is that things could be other than they in fact are—that is, things and situations are contingent—while this condition of contingency itself could not be other, that is, it is not itself contingent. Shifting freely the terms of Meillassoux’s equation, Slotawa’s practice delivers one essential lesson: notwithstanding the contingency of individual compositions that are overwhelmed by the arbitrary, composition as a generative horizon of appearance is absolutely necessary.

Leaving the studio I ask Slotawa what he is doing for P.S.1 in the autumn. He looks very relaxed, smiles, and says, “I don’t know yet.”” – John Chilver is an artist and writer based in London. His texts have appeared in Starship, Afterall, Art Monthly, and Untitled. He teaches at Goldsmiths College. – via Art Papers

via The Exposure Project