Vik Muniz

Work from his oeuvre.

Lecture on TED Talks.

“Here’s the art history quiz for the day: What connects Leonardo da Vinci to Bosco chocolate syrup? Answer: Vik Muniz, an artist who specializes in unlikely means of not quite fooling the eye and calls the results ”photographic delusions.” Mr. Muniz has copied Leonardo’s ”Last Supper” in chocolate syrup. This is probably a first.

The famous fresco in Milan was already deteriorating in Leonardo’s lifetime because he refused to observe the time-tested rules that fresco painters followed. There are no rules for syrup pictures; the limited amount of unscientific research to date suggests their life expectancy is short. There is a rumor that Mr. Muniz sometimes eats his chocolate pictures (talk about consuming passions) but not before enhancing their prospects for a long and healthy life by photographing them.

What results in this case is a kind of cockamamie tour de force: a copy of a major artwork already frequently copied (preferably on velvet), here blown up large and looking at first glance more like a photograph by the Starn twins than a drawing in Bosco (whatever that looks like). It’s no surprise that Mr. Muniz is attracted to the attitude of Dada and Fluxus art, which he says is ”like conceptual art without a frown.”

His own art will make you smile faster than you can say ”cheese.” ”Vik Muniz: Seeing Is Believing,” at the International Center of Photography Midtown, includes about 100 images from the last decade by this Brazilian-born artist who came to the United States in 1983 and has since wrought gentle mayhem on photographic representation. An interview with the artist in an accompanying book (Arena Editions) by the same name proves he can sometimes be as thoughtful and dryly amusing on the hoof as he is on paper.

Charles Ashley Stainback, the Dayton Director of the Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College, is the curator of this first museum survey of Muniz’s work, which insists that things are seldom what they seem but are in fact mostly illusion, and that most of what we know we know through representation — which we don’t even remember very well, so we may not know it after all.

These are not exactly new ideas, but Mr. Muniz serves them up in a relaxed, slyly humorous and occasionally goofy manner, as if Jean Baudrillard had appeared in a Hawaiian shirt, brandishing hot dogs and offering to barbecue them on a drawing of a stove.

At Wooster Gardens in SoHo, ”Flora Industrialis,” a new portfolio of 20 pictures, shows Mr. Muniz in uncommonly beautiful form but without the swift wit of some of the material at the international center. These pictures of individual flowers on dark grounds, heraldically displayed and richly toned to resemble late 19th-century specimen photographs, are actually loving portraits of fake flowers. Unreal flowers (or perhaps real fakes), they are copies at one remove from reality, so realistic that only the camera’s famously realistic reproduction of reality reveals their fakery.

Mr. Muniz generally prefers to invent his own fakes. ”Personal Articles” is a bulletin board cluttered with illustrated newspaper articles. One reports that small cameras have been outlawed in Yosemite. (This should have been headlined ”Making the World Safe for Ansel Adams.”) Another informs us that the Pentagon has admitted engineering the dyslexia virus. Yet another says a National Geographic photographer has been accused of falsifying nature documents by constructing images from his girlfriend’s underwear; the illustration resembles neither nature nor any known piece of lingerie.

These clippings, which hover at the edge of credibility, suggest that (a) paranoia and conspiracy theories are so widespread that for many people almost anything might be true; (b) photographs are manipulated so easily that almost anything might seem to be true; (c) real news has become so wacky that almost anything really might be true, and (d) who can tell what’s true?

Mr. Muniz dances the rhumba with visual perception and temporarily fools the viewer into thinking it’s a samba. In the book he says: ”I have neither the interest nor the means to produce illusions that expand the concept of what an illusion is — George Lucas and Steven Spielberg are doing that for us . . . I want to make the worst possible illusion that will still fool the eyes of the average person.”

So his ”Pictures of Wire” look like drawings, which they are in a way, but photographs of drawings, and the drawings are made of wire rather than traced by a pen or pencil. These simple images of a light bulb, a roll of toilet paper, a spiral notebook, are nearly as pure and elegant as drawings by Ellsworth Kelly, if a good deal shakier. A part of the viewer’s pleasure lies in discovering the agreeable deception at their core.

Mr. Muniz also makes drawings — I guess you can call them that — out of thread, amazingly complex renditions of landscapes, some copied from Corot or Claude Lorraine or Courbet. He uses as much as 17,500 yards at a time, photographs the final image, then scraps it and uses the thread for another picture.

This process is some rigorous form of artistic or perhaps ecological insanity, akin to performance art at its most exhausting, expending all that time, effort and skill on a photograph and then simply unraveling the model. Still-life photographers (and Bosco photographers) can at least eat the mise en scene. Photographers in the last couple of decades have been building elaborate environments for the sole purpose of photographing them; whether the garbage police have succeeded in getting them to recycle remains unclear.

Mr. Muniz specializes rather in materials unavailable at Pearl Paint. He has tried everything from M & M’s to live ants, rubber bands, black beans, electric sparks, oil and milk, but alas, without success, so he has had to resort to dirt, sugar, cotton, wire, thread, chocolate.

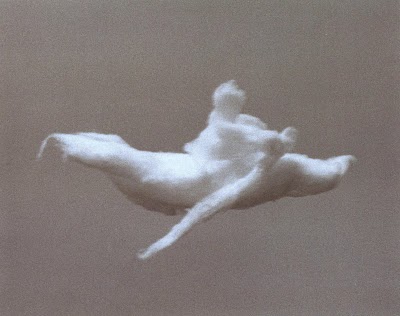

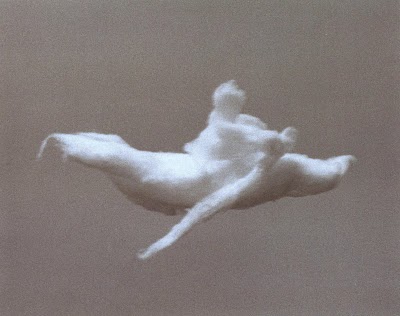

His ”Equivalents” are pictures of floating cotton ”clouds” that faintly resemble a cat, a snail, a rowboat and Alfred Stieglitz’s cloud photographs by that name. He copied his own photographs of the children of sugar-cane workers in sugar itself, grain by grain, then photographed the results. His pictures of nudes, hands, binoculars, a fish made of dirt cleaned speck by speck with miniature vacuum cleaners, Q-tips and straws are puzzlingly, beautifully convincing; they appear at first glance like photographs double exposed onto pictures of earth. His stereo images of such microscopic rarities as ”Vocal Cords Saying ‘Bon Giorno,’ ” the ”loser gene” and the ”sloth virus” were composed of spaghetti strands and a double helix of cheese doodles.

He could, if he wished to, point to a proud tradition for such work. In the age of mechanical reproduction there has arisen among image junkies an insatiable urge to copy major images by hand in materials cadged from the fridge: the Bikini Atoll blast atop a cake, Michelangelo’s David in ice, Iwo Jima in hamburger (as well as gunboats made of roses and topiary dinosaurs). God knows what goes into all those Statues of Liberty outside souvenir shops.

One of Mr. Muniz’s series, ”The Best of Life,” comments on the impact of photographic images. He drew some of the most famous photographs of the century from memory, then photographed the drawings and printed them through a half-tone screen as Life magazine did. At first they look like badly printed photographs until you realize something is off — an arm’s too long, a figure’s missing. If his memory is a little wrong, yours probably is too, so what is it that we remember when we all remember the same thing?

John G. Morris, author of ”Get the Picture: A Personal History of Photojournalism,” pointed out to me that none of the photographers of these images is credited. Corot and Courbet are named, but not Nick Ut for the child running from napalm, John Filo for the Kent State shooting, Stuart Franklin for the man stopping the Chinese tanks in Beijing, Joe Rosenthal for Iwo Jima, Eddie Adams for the Saigon execution of a Vietcong suspect, Alfred Eisenstaedt for the kiss at Times Square, J. R. Eyerman for a 3-D screening, Bob Gruen for John Lennon in Manhattan and Neil Armstrong for the man on the moon.

This is curious. Is it unfair appropriation, or are the most urgent images of our time effectively anonymous? Are the authors of news images erased or subsumed by the contents of their pictures? Have the most memorable images become such public property that they no longer need credit, whereas the less memorable images by artists still do?

Taken all in all, Vik Muniz’s work tells us that seeing is not quite believing, that perceiving and understanding are balancing acts, that experience itself is a see-saw. This is a drawing, he says, but then again, maybe it’s not. Ceci n’est pas un Corot.

What it is is an idea wrapped up in surprise and laughter. You might just give up Prozac for the day and see this show instead.” – Vicki Goldberg for the New York Times