Frank Kunert

Work from Photographs of Small Worlds.

Ironically, the first time I cam across Kunert’s work it was in a spam email titled “Award Winning Construction Projects” that featured the bottom image. Kunert is another example of why I am so grateful that I abandoned my model making project in its infancy.

“The project “Small Worlds” is far from being mere photographic satire. Instead, Kunert has spent weeks, sometimes even months, working with deco boards, plasticine and paint, in order to model his thoughts in 3D. With an exceptional eye for detail, he has constructed faultless models, and created scenes that look just like the real thing. Kunert never flicks on his studio lights and reaches for his large-format camera until he feels that his models have reached a state of perfection — until they have become little worlds of their own.

And, it is true, these intricate models could very well stand on their own. But by taking photographs of them, the complexity of these elaborately staged worlds (as well as the intended visual illusion they create) is made manifest. For Kunert, photo montage and computer animation do not come into question. He has no interest in getting fast results, or of achieving a perfect high-gloss surface. In his mind, it is not only perfectly acceptable that viewers of his large prints can detect that these are pictures taken of models; they should actually be aware of this fact. The “analogue look” of his photographs is intentional — Kunert’s answer to digitalization is creating images of the tangible.

Frank Kunert’s “Small Worlds” are, in their symbiosis of idea, image and caption, just as multi-dimensional as excellently-crafted written narratives. On the surface, these photographs confront us with all of the hollow words, catchphrases and banalities we encounter in our daily lives. The stereotypical and senseless aspects of human communication cannot be unveiled more convincingly than in their literal conversion into a visual medium. Kunert deliberately oscillates between humor, wit, scurrility and the grotesque. If, indeed, “Life goes on,” then, there is no question about it, it is only with the continued delivery of one’s daily paper and mail. The tombstone will, of course, need a mailbox and a doorbell, and Mr. Kunert has naturally taken both into account.

On a deeper level, these “Small Worlds” are linked by a reoccurring motif: our deep human desire for security and our fear of loss, as well as our anxiety regarding the transitory nature of life. It is no accident that, despite all of the foliage depicted, there is not a single photograph in this collection that evokes a feeling of summer. In addition, Kunert does not portray secluded suburbia as a neat row of townhouses with carports, but rather as buildings that stem from the early post-war period. Melancholy and dejection pervade these images. “Near the autobahn” illustrates how justified we are in fearing the loss of our sense of safety on an individual level. Here, the freeway literally runs through a residential neighborhood, depriving its inhabitants of any possibility of finding a calm, solitary and safe place to retreat to. The same applies to the photograph entitled “Sunny side”: no matter how hard the tenants of this apartment scrub and sweep, or decorate the balcony with potted plants, the plants will shrivel, and there will be no getting away from the traffic.

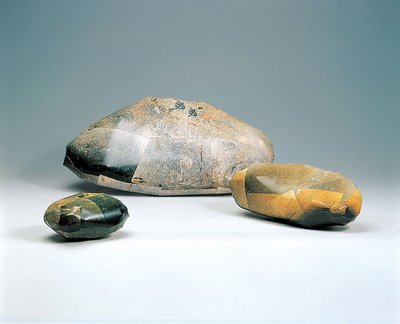

With his “Small Worlds,” Frank Kunert confronts a further menacing loss that our experience-driven “fun society” will undoubtedly encounter in the near future: the loss of imaginativeness and invention in the face of entertainment overload, which has already turned small-town, country-style inns and locales into event gastronomies, and made so-called “adventure pool complexes” out of quaint public indoor swimming pools. The fact that Kunert feels neither affected nor threatened by this loss himself can be gleaned from each and every one of his photographs, as well as the very apparent inexhaustibility of his ideas. Just how much work, time and effort has been put into spinning his visual tales, with seeming ease, becomes readily apparent in the sample models that the artist puts on display when he exhibits his photography, even if the viewers only ever get to see pieces of them.

Kunert’s art has often been rightfully compared to the poems of Robert Gernhardt. Kunert’s “Small Worlds” are equally funny, whimsical, grotesque, and pensive musings, and they are also provocative and critical. It is left up to the viewers to decide if they find the works morbid, or simply funny; if they want to truly see the deeper level of what the stories are telling them, and if they might even dare to elaborate on them.” – (This text appears by the kind courtesy of Dr. Christine Donat.)

via PYTR 75 (thanks to Mrs. Dean for posting a link to PYTR75)