Harrison Haynes

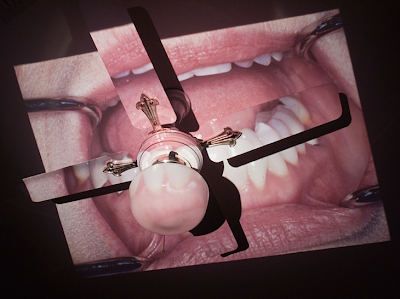

Work from Distruptive Patterns.

“LB: Your work often contains an isolated object/figure in an open field as is the case here. Is this an aspect of the work, or a way of discussing the work?

HH: I have a preoccupation with decontextualization. Focusing on details or objects within my everyday surroundings and thinking about what they might mean outside of their original environment, what they might mean to the viewer and also what they mean to me. The latter question is a more recent one. I’m trying to better understand my own intuitive approach to visual taxonomy/subject matter. i.e., what do I ‘gravitate towards’ and why?

Kudzu was just something I saw my whole life, an omnipresent part of the landscape of NC. Moving away and returning a few times probably allowed me to see it for what it is: an insane monster of a plant that forms some very compelling shapes as it blankets the tree line.

Isolation in this collage-Untitled (Form 1), 2009-is literally manifested. The discrepancy between the figure and the ground is amplified: overwrought density in form (collaged photos of kudzu) and absolute neutrality/negativity in the background (raw canvas). So, I guess it’s both an aspect of, and a talking point in the work.

LB: I am curious how this interest in decontextualization might inform your material choices? You could say that this ‘removal of details from the world’ constitutes a definition of a photographic practice, but you have often chosen other means like collage or painting. Do you see the snapshots used in your collages as things to be decontextualized? Are the photographs as objects themselves aspects to be isolated? In short, I am interested in why you choose to construct the image out of physical photographs rather than make the same kind of juxtapositions digitally, and whether or not this has to do with the photograph itself as a detail of everyday surroundings to be manipulated and focused on?

HH: I wanted to use the cut up pieces of photos as a material to describe something layered and leafy like kudzu. There’s that direct sculptural impetus. I also like the redundancy of it: using photos of kudzu to make a sort of clumsy recreation of kudzu. It has a deadpan quality.

LB: I really like this notion of clumsiness! I feel that there is a lot of power in giving someone a mechanical vantage point; a view of the parts as well as the whole. I am wondering about another level of the relationship between kudzu (or the clutter of yard sales from other pieces) and photography. Would it be a stretch to say that there is a relationship between the ubiquity of photographs and the more insidious colonization of the plant?

HH: No I don’t think its a stretch, although those connections might not reveal themselves until later in the process. The palimpsest-y quality of kudzu, or any rampant vine, like English Ivy or Virginia Creeper, is hard to miss. And it’s as much a symbol of decimation as it is of progress. Or, you could characterize it as an obsolete and now reviled technology, like Asbestos. I do connect it to the phenomenon of piled up crap.

LB: I would like to talk for a second about kudzu as as an obsolete technology which is a really great way to frame it, and to come back to this tactic of redundancy you mentioned earlier. In these terms your work, or at least these collage pieces, are dealing with obsolete technologies (kudzu, piles of junk, photographic prints) in both material and content. I think this delimits collage practice in a really interesting way, where I think it normally slips into a much less discursive space.

HH: I want to tell a little bit about the histories of kudzu and collage. Kudzu was imported from Asia and marketed to the South Eastern US agricultural industry in the early 20th c. as an impediment to erosion (all that slippery red clay). As a non-native species, it lacked natural predators and on top of that can grow as much as a foot a day. It is also very hard to kill, so that now we’ve got this crazy homogeneous backdrop along roadsides from Virgina to Florida.

Collage was also once a radical technology, a way to break up space on the picture plane. And it caused a huge tectonic shift in the way we think about and make art. I’ve been reading Ann Baldassari’s book Picasso & Photography: The Dark Mirror. It’s an incredible reminder of how significantly Picasso changed everything in the early part of the last century. The Picasso work she focuses on (especially the studio tableau photographs) is so pertinent to what many artists are doing right now. Also, George Baker’s The Artwork Caught by the Tail: Francis Picabia and Dada in Paris, is a good companion, as it chronicles Picabia’s practice right around the same time. Interdisciplinarity is at the forefront of both artists’ approach and collage could be described as a micrcosm of that approach, since it compounds elements of sculpture and painting, and with Picasso, photography.

But collage isn’t new any more, and it’s use has trickled down to even the most quotidian realms. So, to use collage now requires an acknowledgement of how far away we are from that moment of innovation. I think my collages are less about that radical, shocking disruption of space and more about using the technique to depict something rather ordinary. I named the series of collages ‘Disruptive Patterns’ after the science of camouflage which uses the fragmentation of positive and negative shapes to create an atmospheric, invisible field, something not there, something marginalized.” – excerpt from a discussion with Lucas Blalock on The Photography Post.