Jon Rafman

Work from Google Street Views.

“Two years ago, Google sent out an army of hybrid electric automobiles, each one bearing nine cameras on a single pole. Armed with a GPS and three laser range scanners, this fleet of cars began an endless quest to photograph every highway and byway in the free world.

Consistent with the company’s mission “to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful,” this enormous project, titled Google Street View, was created for the sole purpose of adding a new feature to Google Maps.

Every ten to twenty meters, the nine cameras automatically capture whatever moves through their frame. Computer software stitches the photos together to create panoramic images. To prevent identification of individuals and vehicles, faces and license plates are blurred.

Today, Google Maps provides access to 360° horizontal and 290° vertical panoramic views (from a height of about eight feet) of any street on which a Street View car has traveled. For the most part, those captured in Street View not only tolerate photographic monitoring, but even desire it. Rather than a distrusted invasion of privacy, online surveillance in general has gradually been made ‘friendly’ and transformed into an accepted spectacle.

One year ago, I started collecting screen captures of Google Street Views from a range of Street View blogs and through my own hunting. This essay illustrates how my Street View collections reflect the excitement of exploring this new, virtual world. The world captured by Google appears to be more truthful and more transparent because of the weight accorded to external reality, the perception of a neutral, unbiased recording, and even the vastness of the project. At the same time, I acknowledge that this way of photographing creates a cultural text like any other, a structured and structuring space whose codes and meaning the artist and the curator of the images can assist in constructing or deciphering.

Street View collections represent our experience of the modern world, and in particular, the tension they express between our uncaring, indifferent universe and our search for connectedness and significance. A critical analysis of Google’s depiction of experience, however, requires a critical look at Google itself.

Initially, I was attracted to the noisy amateur aesthetic of the raw images. Street Views evoked an urgency I felt was present in earlier street photography. With its supposedly neutral gaze, the Street View photography had a spontaneous quality unspoiled by the sensitivities or agendas of a human photographer. It was tempting to see the images as a neutral and privileged representation of reality—as though the Street Views, wrenched from any social context other than geospatial contiguity, were able to perform true docu-photography, capturing fragments of reality stripped of all cultural intentions.

The way Google Street View records physical space restored the appropriate balance between photographer and subject. It allowed photography to accomplish what culture critic and film theorist Siegfried Kracauer viewed as its mission: “to represent significant aspects of physical reality without trying to overwhelm that reality so that the raw material focused upon is both left intact and made transparent.”

This infinitely rich mine of material afforded my practice the extraordinary opportunity to explore, interpret, and curate a new world in a new way. To a certain extent, the aesthetic considerations that form the basis of my choices in different collections vary. For example, some selections are influenced by my knowledge of photographic history and allude to older photographic styles, whereas other selections, such as those representing Google’s depiction of modern experience, incorporate critical aesthetic theory. But throughout, I pay careful attention to the formal aspects of color and composition.

Within the panoramas, I can locate images of gritty urban life reminiscent of hard-boiled American street photography. Or, if I prefer, I can find images of rural Americana that recall photography commissioned by the Farm Securities Administration during the depression.

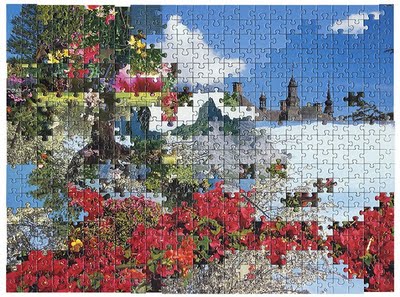

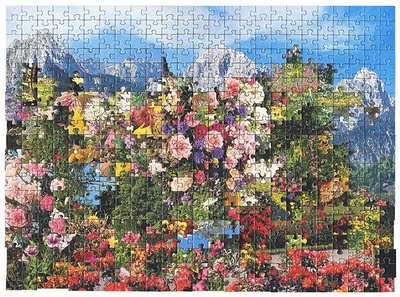

I can seek out postcard-perfect shots that capture what Cartier-Bresson titled “the decisive moment,” as if I were a photojournalist responding instantaneously to an emerging event.

At other times, I have been mesmerized by the sense of nostalgia, yearning, and loss in these images—qualities that evoke old family snapshots.

I can also choose to be a landscape photographer and meditate on the multitude of visual possibilities.

Or I can search for passing scenes that remind me of one of Jeff Wall’s staged tableaux.

Although Street View stills may exhibit a variety of styles, their mode of production—an automated camera shot from a height of eight feet from the middle of the street and always bearing the imprimatur of Google—nonetheless limits and defines their visual aesthetic. The blurring of faces, the unique digital texture, and the warped sense of depth resulting from the panoramic view are all particular to Street View’s visual grammar.

Many features within the captures, such as the visible Google copyright and the directional compass arrows, continually point us to how the images are produced. For me, this frankness about how the scenes are captured enhances, rather than destroys the thrill of the present instant projected on the image.

Although Google’s photography is obtained through an automated and programmed camera, the viewer interprets the images. This method of photographing, artless and indifferent, does not remove our tendency to see intention and purpose in images.

This very way of recording our world, this tension between an automated camera and a human who seeks meaning, reflects our modern experience. As social beings we want to matter and we want to matter to someone, we want to count and be counted, but loneliness and anonymity are more often our plight.

But Google does not necessarily impose their organization of experience on us; rather, their means of recording may manifest how we already structure our experience.

Street Views can suggest what it feels like when scenes are connected primarily by geographic contiguity as opposed to human bonds.

A street view image can give us a sense of what it feels like to have everything recorded, but no particular significance accorded to anything.

These collections seek to convey contemporary experience as represented by Google Street View. We are bombarded by fragmentary impressions and overwhelmed with data, but we often see too much and register nothing. In the past, religion and ideologies often provided a framework to order our experience; now, Google has laid an imperial claim to organize information for us. Sergey Brin and Larry Page have compared their search engines to the mind of God and proclaimed as their corporate motto, “do no evil.”

Although the Google search engine may be seen as benevolent, Google Street Views present a universe observed by the detached gaze of an indifferent Being. Its cameras witness but do not act in history. For all Google cares, the world could be absent of moral dimension.

The collections of Street Views both celebrate and critique the current world. To deny Google’s power over framing our perceptions would be delusional, but the curator, in seeking out frames within these frames, reminds us of our humanity. The artist/curator, in reasserting the significance of the human gaze within Street View, recognizes the pain and disempowerment in being declared insignificant. The artist/curator challenges Google’s imperial claims and questions the company’s right to be the only one framing our cognitions and perceptions.” – Jon Rafman for Art Fag City